Abstract

Background

Dysregulated lipid metabolism is critically involved in the development of hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC). The respective metabolic pathways affected in HCC can be identified using suitable experimental models. Mice injected with diethylnitrosamine (DEN) and fed a normal chow develop HCC. For the analysis of the pathophysiology of HCC in this model a comprehensive lipidomic analysis was performed.

Methods

Lipids were measured in tumor and non-tumorous tissues by direct flow injection analysis. Proteins with a role in lipid metabolism were analysed by immunoblot. Mann-Whitney U-test or paired Student´s t-test were used for data analysis.

Results

Intra-tumor lipid deposition is a characteristic of HCCs, and di- and triglycerides accumulated in the tumor tissues of the mice. Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma coactivator 1 alpha, lipoprotein lipase and hepatic lipase protein were low in the tumors whereas proteins involved in de novo lipogenesis were not changed. Higher rates of de novo lipogenesis cause a shift towards saturated acyl chains, which did not occur in the murine HCC model. Besides, LDL-receptor protein and cholesteryl ester levels were higher in the murine HCC tissues. Ceramides are cytotoxic lipids and are low in human HCCs. Notably, ceramide levels increased in the murine tumors, and the simultaneous decline of sphingomyelins suggests that sphingomyelinases were involved herein. DEN is well described to induce the tumor suppressor protein p53 in the liver, and p53 was additionally upregulated in the tumors.

Conclusions

Ceramides mediate the anti-cancer effects of different chemotherapeutic drugs and restoration of ceramide levels was effective against HCC. High ceramide levels in the tumors makes the DEN injected mice an unsuitable model to study therapies targeting ceramide metabolism. This model is useful for investigating how tumors evade the cytotoxic effects of ceramides.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Hepatocellular carcinoma is a hard-to-cure malignancy and the incidence has progressively increased over the last decades [1,2,3]. Metabolic reprogramming is a hallmark of cancers during disease initiation and progression. Various studies have documented a higher expression of enzymes involved in de novo lipogenesis in human HCC tissues [4,5,6,7,8]. Ablation of fatty acid synthase (FAS) prevented the proliferation of HCC cells in-vitro and also delayed hepatocarcinogenesis in experimental models [9,10,11,12]. Further analysis showed that cholesterol biosynthesis was enhanced upon blockage of FAS in HCC cell lines and in the murine liver [10]. Of note, ablation of fatty acid and cholesterol biosynthesis completely prevented tumorigenesis in the liver of a murine HCC model induced by loss of Phosphatase and Tensin homolog and overexpression of c-Met [10]. Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma coactivator 1 alpha (PGC1alpha) increases fatty acid oxidation and lowers hepatic triglyceride storage and secretion [13]. PGC1alpha was downregulated in human HCC tissues and low expression was associated with a poor prognosis. Thus, emerging evidence indicates that lipids are important for the development and progression of HCC and may be targets for HCC therapies [5, 7, 10].

Pathogenesis of HCC is highly complex, and persistent inflammation is well known to promote carcinogenesis [14,15,16]. Strikingly, increasing evidence points at a functional connection of lipid metabolism and inflammation [15]. Saturated fatty acids are well described to activate pro-inflammatory signalling pathways in immune cells [17]. Liver steatosis is associated with an increased synthesis of inflammatory proteins by hepatocytes and leads to the activation of Kupffer cells [18]. Dietary fat induces the production of inflammatory cytokines in adipose tissues that may play a role in hepatic inflammation [19, 20]. PGC1alpha downregulation is associated with lipid deposition, oxidative stress and inflammation [21]. Liver steatosis was furthermore associated with an altered gut microbiota, higher intestinal permeability and increased gut-derived endotoxin levels, again linking lipid metabolism and inflammation [22].

The cancer lipidome of HCC patients has been analysed in a few studies so far [5]. These analyses described that triglycerides accumulated in human HCC tissues [23,24,25]. Aberrant activation of de novo lipogenesis favours the accumulation of saturated fatty acids and there was a shift from polyunsaturated to saturated lipids in human HCCs [24,25,26].

Deposition of excess cholesterol was also noted in human HCC tissues [27, 28]. Cholesterol biosynthesis and uptake is regulated by sterol regulatory element binding protein (SREBP) 2 [29]. SREBP2 increases the expression of various genes such as 3-hydroxy-3-methyl-glutaryl-CoA reductase and the low-density lipoprotein receptor (LDL-R). Emerging evidence indicates that blockage of SREBP2 may be effective to treat different cancers such as HCC [30]. Hepatic uptake of LDL is also regulated by proprotein convertase subtilisin/kexin type 9 (PCSK9), which induces the lysosomal degradation of the LDL-R [31]. Low expression of PCSK9 and high expression of the LDL-R in human HCCs [32] suggests that this pathway contributes to cholesterol overload of the tumors.

Ceramides are a relatively well studied lipid class and have a role in various cellular processes [33]. There is convincing evidence that ceramide function depends on its acyl-chain length [5, 34]. The long-chain species (C16 - C20) increase insulin resistance, cell death and oxidative stress and the very long-chain derivatives (C22 - C24) have the opposite effects [5, 34]. Ceramide levels were low in human HCCs, and thus, it was supposed that shorter chain ceramides protect from tumor progression [24,25,26, 35]. Short-chain ceramides delivered by nanoliposomes were indeed effective against HCC [33, 36,37,38]. Notably, chemotherapeutics induce ceramide production that mediates the anti-proliferative and pro-apoptotic effects of these drugs [33].

Potential HCC therapies are being tested in suitable experimental models [39]. The most widely used approach to induce liver cancer in rodents is a single injection of diethylnitrosamine (DEN) to young mice. The time required for tumor development varies with DEN dose, mouse strain, and sex [40].

Only little data is available on the lipidome of murine tumors in the DEN model. Considering that lipids have a central role in cell viability, proliferation and inflammation [5, 18, 41, 42], a detailed lipidomic analysis will help to further understand tumor pathology and to develop lipid-based therapies. Moreover, a comprehensive characterization of the HCC lipidome makes it possible to choose the most appropriate murine model.

Mice fed a low methionine, choline-deficient chow, when injected with DEN at a young age, develop HCC. Unexpectedly, expression of FAS and acetyl-CoA-carboxylase was low in the tumors. Accordingly, triglycerides and diglycerides were reduced in the HCC tissues of these animals compared to non-tumor liver tissues [43]. A prominent decline of ceramides was not observed in the tumors of those mice. Thus, the tumor lipidome of these animals did not resemble the lipid changes observed in human HCCs [5, 43].

Male C3H/HeNRj (25 mg/kg DEN injected at 18–21 days of age), which were fed a normal chow, accumulated diglycerides, triglycerides and cholesterol in the tumors [44]. Excess of these lipid classes was described in human HCCs [5]. Aim of the present investigation was to clarify whether these mice are a suitable model to study the role of lipid dysregulation described in human HCC. For this purpose, a comprehensive analysis of the tumor lipidome was performed. Besides, several proteins with a role in cholesterol and triglyceride metabolism were analysed to identify the proteins underlying these changes in lipid composition.

Materials and methods

Animals

The animals used in the present study served as controls in a previous investigation and were injected with adeno-associated virus 8 (AAV8) particles without any cloned DNA [44]. AAV8 vectors are being used in various animal models without any severe adverse effects [45]. Thus it is unlikely that AAV8 greatly affects the lipidome [46].

Animal model: Male C3H/HeNRj mice (Janvier Labs, Le Genest-Saint-Isle, France) were injected with DEN (Sigma, Taufkirchen, Germany; 25 µg/g body weight) at 18–21 days of age. A total of 24 weeks later, AAV8 without any cloned DNA (1012 particles per mouse) were intraperitoneally injected, and the mice were killed 13 weeks later. These mice were fed a standard chow (V1124-300, Mouse breading 10 mM autoclavable, Ssniff, Soest, Germany) throughout the study. Normal liver tissues of 12 mice and tumorous liver tissues of 10 mice were used in the current analysis. Mice killed 37 weeks after DEN injection developed a variety of liver tumors. Tumor diameter ranged from < 1 mm to > 10 mm [44]. Liver tumors that were clearly distinguishable from normal liver tissue were excised using a pair of binoculars. These tissues are suitable for the purpose of the current investigation where normal liver and tumors were compared. Reuse of these tissues also considers the 3Rs to improve animal welfare [47].

Mice had free access to water and food and were housed in a 21 ± 1 °C controlled room under a 12 h light-dark cycle. All procedures were in accordance with the institutional and governmental regulations for animal use (Approval number 54-2532.1-21/14, 03,11,2014).

Mass spectrometric analysis

Lipids were extracted from 2 mg liver tissues as was described by Bligh and Dyer [48]. Non-naturally occurring lipid species, which served as internal standards, were added during lipid extraction (Internal standards: PC 14:0/14:0, PC 22:0/22:0, PE 14:0/14:0, PE 20:0/20:0 (di-phytanoyl), PS 14:0/14:0, PS 20:0/20:0 (di-phytanoyl), PI 17:0/17:0, LPC 13:0, LPC 19:0, LPE 13:0, Cer d18:1/14:0, Cer d18:1/17:0, D7-FC, CE 17:0, CE 22:0, TG 51:0, TG 57:0, DG 28:0 and DG 40:0). The chloroform phase was vacuum dried and the leftover was solubilized in chloroform/methanol/2-propanol (1:2:4 v/v/v) with 7.5 mM ammonium formate (for high resolution mass spectrometry) or in methanol/chloroform (3:1, v/v) with 7.5 mM ammonium acetate (for low mass resolution tandem mass spectrometry).

Lipids were analyzed by direct flow injection analysis and this was described elsewhere [43, 49,50,51,52]. Direct flow injection analysis (FIA) using a triple quadrupole mass spectrometer (FIA-MS/MS; QQQ triple quadrupole) and a hybrid quadrupole-Orbitrap mass spectrometer (FIA-FTMS; high mass resolution) were used. FIA-MS/MS (QQQ) was carried out in positive ion mode as was already described [49, 52]. A fragment ion of m/z 184 was employed for lysophosphatidylcholines (LPCs) [50]. The neutral loss applied for phosphatidylethanolamine (PE) was 141, for phosphatidylserine (PS) was 185, and for phosphatidylinositol (PI) was 277 [53]. Sphingosine based ceramides (Cer) were determined using a fragment ion of m/z 264 [51].

The Fourier Transform Mass Spectrometry (FIA-FTMS) method was described by Höring et al. [54]. Triglycerides (TGs), diglycerides (DGs) and cholesteryl ester (CE) were determined in positive ion mode FTMS in range m/z 500–1000 for 1 min with a maximum injection time (IT) of 200 ms, an automated gain control of 1*106, three microscans and a target resolution of 140,000 (at m/z 200). Phosphatidylcholine (PC) and sphingomyelin (SM) were measured in range m/z 520–960. Multiplexed acquisition was used for the [M + NH4]+ of free cholesterol (FC) (m/z 404.39) and D7-cholesterol (m/z 411.43) for 0.5 min acquisition time, with a normalized collision energy of 10 %, an IT of 100 ms, automated gain control of 1*105, isolation window of 1 Da, and a target resolution of 140,000 (at m/z 200). Data processing by the use of the ALEX software [55] and self-programmed Macros (Microsoft Excel 2010) was described previously [56]. Lipid species were noted according to the shorthand notation of lipid structures derived from mass spectrometry analysis [57]. For QQQ glycerophospholipid species even numbered carbon chains were assumed. Liver lipids are given as nmol/mg wet weight.

Immunoblotting

Immunoblotting was carried out as described [58]. Antibodies for glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) (order number: 2118), phosphorylated (p)ACC (order number: 3661), pAMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK; order number: 2351), AMPK (order number: 2532), hormone sensitive lipase (HSL) (order number: 4107), stearoyl-CoA-reductase (SCD1) (order number: 2794), cyclophilin A (order number: 2175) and fatty acid synthase (FAS) (order number: 3189) were from Cell Signaling (Frankfurt am Main, Germany). Hepatic lipase (LIPC) antibody (order number: LS-C331464-50) was from LSBio (Seattle, Washington, United States). Apolipoprotein (Apo) B (order number: MA5-35458 ), ApoE (order number: ab947), ApoAII (order number: 178424), lipoprotein lipase (LPL) (order number: BS-23,362), diacylglycerol-O-acyltransferase (DGAT) 2 (order number: PA5-103785), SREBP1c (order number: MS-1207-P1ABX) and manganese superoxide dismutase (MnSOD) (order number: LF-PA0021) antibodies were from Thermo Fisher Scientific (Schwerte, Germany). Acetyl-CoA-carboxylase (ACC) (order number: MAB 6898), CD36 (order number: NB400-145), scavenger receptor BI (order number: NB400-104) and DGAT1 (order number: NB-110-4148755) antibodies were from Novus Biologicals (Wiesbaden-Nordenstadt, Germany). The PCSK9 (order number: AF3985), LDL-receptor (order number: AF2255-SP) and p53 (order number: AF1355) antibodies were from R&D Systems (Wiesbaden-Nordenstadt, Germany). PGC1alpha antibody was from Abcam (Cambridge, UK, order number: ab106814). SREBP2 antibody was from Caymen Chemical (Hamburg. Germany; order number: 10,007,663).

Real-time RT-PCR

RNA was purified using the AllPrep DNA/RNA/Protein Mini Kit (Qiagen, Hildesheim, Germany). RT-PCR was performed as described in detail [44]. LDL-receptor was amplified with 5´ GAT GGC TAT ACC TAC CCC TCA A 3´ and 5´ CCT TTT CTG TCC CCA GAC AA 3´. PGC1alpha was amplified with 5´ GGA ATG CAC CGT AAA TCT GC 3´ and 5´ AAA ATC CAG AGA GTC ATA CTT GCT C 3´. For normalisation, cyclophilin A was used and primers were 5´ AAC ACA AAC GGT TCC CAG TT 3´and 5´ TTG AAG GGG AAT GAG GAA AA 3´.

GeneChip analysis

The Mouse Gene 2.1. ST Array (Affymetrix, Schwerte, Germany) was hybridized with RNA from normal liver and HCC tissues of five animals. Hybridization and data analysis was performed by the Kompetenzzentrum für Fluoreszente Bioanalytik (Regensburg, Germany). The P-value for AFP regulation (Table 2), which was shown previously to be induced in tumors of DEN-injected mice [59], was chosen as cut off value.

Statistical analysis

Data are shown as box plots. Outliers are identified by small circles and extreme values are marked with stars. Orange and red circles in the figures are the individual values measured. Quantification of proteins was done using ImageJ [60]. Data of proteins, which were not changed in the tumor tissues, are shown as mean ± standard deviation. Statistical differences were calculated by Mann-Whitney U-test or paired Students´t-test. Spearman correlation analysis was also used (SPSS Statistics 25.0 program; IBM, Leibniz Rechenzentrum, Munich, Germany). Values of P < 0.05 were considered as significant.

Results

Triglyceride and diglyceride accumulation in the tumor tissues

Triglyceride (TG) deposition was observed in the murine tumors (Fig. 1a and [44]). Saturated, monounsaturated (MU) and polyunsaturated (PU) TGs were increased (Fig. 1b-d). Diglycerides (DGs) also accumulated in the cancer tissues (Fig. 1e and [44]), and saturated, MU-DG and PU-DG levels were high in the tumors (Fig. 1f-h). The PU/saturated TG ratio was 545 (271–2001) in the normal liver and increased to 1246 (750–1987) in the tumors (P = 0.017). The PU/saturated DG ratio was 78 (45–133) in the non-tumor tissues and 92 (76–194) in the HCC tissues (P = 0.069).

Levels of triglycerides (TGs) and diglycerides (DGs) in the normal tissues (NT) and tumor tissues (TT) of mice injected with diethylnitrosamine (n = 9–12 mice). a Hepatic TGs. b Saturated (sat) TGs. c Monounsaturated (MU) TGs. d Polyunsaturated (PU) TGs. e Hepatic DGs. f Sat DGs. g MU-DGs. h PU-DGs. ** P < 0.01; *** P < 0.001

Lipoprotein lipase, hepatic lipase and PGC1alpha are downregulated in the tumors

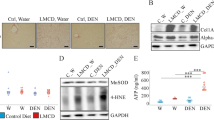

Activation of SREBP1c was comparable in non-tumor and tumor tissues of these mice (Supplementary Fig. 1a and [44]). Accordingly, stearoyl-CoA-reductase, fatty acid synthase (FAS) and acetyl-CoA carboxylase (ACC) levels were not induced in the tumors (Supplementary Fig. 1a and Fig. 2a, h). The ratio of phosphorylated to not phosphorylated ACC did not change in the tumors (Fig. 1a, d). Hormone sensitive lipase, diacylglycerol O-acyltransferase (DGAT) 1 and 2 were similar in tumor and non-tumor tissues (Fig. 2a, b, h). AMPK and its phosphorylated form were not changed in the tumors (Fig. 2b, d). CD36 tended to decline (P = 0.05), while lipoprotein lipase (LPL), PGC1alpha and hepatic lipase (LIPC) proteins were all low in the tumors (Fig. 2b, c, e - g). PGC1alpha mRNA expression was, however, not changed in the HCC tissues (Table 1).

Enzymes with a role in TG synthesis in the normal tissues (NT) and tumor tissues (TT) of mice injected with diethylnitrosamine. a Expression of ACC, pACC, FAS, and HSL. b Expression of DGAT1, DGAT2, pAMPK, AMPK and CD36. c Expression of LPL, PGC1alpha and LIPC. Cyclophilin A (CycA) was a further housekeeping protein analysed. d Ratio of pACC/ACC and pAMPK/AMPK in NT and TT. e Quantification of LPL protein. f Quantification of PGC1alpha protein. g Quantification of LIPC protein. h Quantification of proteins not changed in the TT. (n = 6–7). * P < 0.05; *** P < 0.001

Global gene expression analysis showed that carnitine palmitoyltransferase 2 (CPT2) mRNA was reduced in the tumors (Table 2). Further genes with a role in fatty acid oxidation such as CPT1a, acyl-Coenzyme A dehydrogenases, enoyl-Coenzyme A, hydroxysteroid (17-beta) dehydrogenase 4 and hydroxyacyl-Coenzyme A dehydrogenase/3-ketoacyl-Coenzyme A thiolase were not differentially expressed between normal and tumor tissues (Table 2 and data not shown). Of note, LIPC mRNA levels were reduced in the murine HCC tissues (Table 2).

Cholesterol, LDL-receptor and ApoB are induced in the tumor tissues

Total cholesterol levels were higher in the murine tumor tissues (Fig. 3a and [44]). Of the six analyzed cholesteryl ester (CE) species (CE16:0, 16:1, 18:1, 18:2, 20:4, 22:6) all but CE20:4 were significantly induced in the cancer tissues (Fig. 3b - d and Supplementatry Fig. 1b). Free cholesterol concentrations did not change (Supplementary Fig. 1b).

Levels of cholesterol and expression of proteins with a role in cholesterol metabolism in the normal tissues (NT) and tumor tissues (TT) of mice injected with diethylnitrosamine. a Hepatic cholesterol. b Cholesteryl ester (CE) 16:0 c CE18:1. d CE22:6. e Expression of the LDL-receptor (LDL-R), PCSK9 and ApoB protein. f Quantification of LDL-R protein. g Quantification of ApoB protein. h Expression of SR-BI, ApoE and ApoAII i Quantification of proteins not changed in the tumor tissues (n = 6–7). * P < 0.05, ** P < 0.01, *** P < 0.001

SREBP2 was, however, not overactivated in the tumors of the mice studied herein (Supplementatry Fig. 1c and [44]). Consequently, LDL-receptor mRNA was not changed in the cancer tissues (Table 1). LDL-receptor protein was nevertheless higher in the HCC tissues (Fig. 3e, f). Notably, apoB protein was strongly increased in the tumors (Fig. 3e, g).

Scavenger receptor BI, proprotein convertase subtilisin/kexin type 9 (PCSK9), apoE and apoAII were similar in tumor and non-tumor tissues (Fig. 2e, h, i).

Ceramide species are elevated in the HCC tissues

Ceramide levels were induced in the tumor tissues and of the seven different ceramide species measured, five were higher in the HCCs (Fig. 4a - e). The ratio of long-chain to very long-chain ceramide species was increased in the tumor tissues (Fig. 4f).

Hepatic ceramide (Cer) and sphingomyelin (SM) levels in the normal tissues (NT) and tumor tissues (TT) of mice injected with diethylnitrosamine (n = 8–12 mice). a Cer (d18:1/16:0). b Cer (d18:1/18:0). c Cer (d18:1/20:0). d Cer (d18:1/23:0). e Cer (d18:1/24:1). f Long-chain (LC; 16–20 N-acyl carbons) / very long-chain (VLC; >20 N-acyl carbons) Cer ratio. g SM40:1;O2. h SM40:2;O2. i SM41:1;O2. j SM41:2;O2 k SM42:1;O2. l SM42:2;O2 species. * P < 0.05, ** P < 0.01, *** P < 0.001

A decline of sphingomyelin (SM) levels was noticed in the HCC tissues (Fig. 4 g - l). Six of the nine different SM species measured were decreased in the HCC tissues (Fig. 4 g - l). The SM/ceramide ratio was markedly reduced in the tumors (data not shown).

Phospholipids are hardly changed in the tumors

Total levels of phosphatidylcholine (PC) and phosphatidylethanolamine (PE), and the phospholipids phosphatidylserine (PS) and phosphatidylinositol (PI) were not changed in the tumors (Fig. 5a, b and Supplementary Fig. 1d). The PC/PE ratio was similar in tumor and non-tumor tissues (Fig. 5c).

Hepatic phosphatidylcholine (PC), phosphatidylethanolamine (PE), phosphatidylserine (PS) and phosphatidylinositol (PI) levels in the normal tissues (NT) and tumor tissues (TT) of mice injected with diethylnitrosamine. (n = 10–12 mice). a PE. b PC. c PC / PE ratio. d Polyunsaturated (PU) PE. e Monounsaturated (MU) PS. f MU-PI. g PC32:1. h PC34:1. i PC34:2. j PC36:3. k PC40:7. l PU-PC. * P < 0.05, ** P < 0.01

Saturated, MU- and PU-PC were not changed in the tumors (Supplementary Fig. 1e). This also applied to MU-PE (data not shown) and PU-PE (Fig. 5d). Saturated PE and PS levels are very low and were not further analysed. MU-PS declined, and MU-PI was higher in the HCC tissues compared to the normal tissues whereas saturated PI, PU-PI and PU-PS levels did not change (Fig. 5e, f and data not shown).

There is some evidence that single PC species are changed in tumors [61]. The concentrations of the two MU-PC species (PC32:1, PC34:1) were similar in the non-tumor and tumor tissues (Fig. 5g, h). Regarding PU-species, PC34:2, 36:3 and 40:7 declined in the tumors whereas PC38:6 did not change (Fig. 5i-k and data not shown).Total PU-PC levels were similar in normal tissues and cancer tissues (Fig. 5l).

Lysophosphospholipids and PE-plasmalogens are hardly changed in the tumors

Lysophosphatidylcholine (LPC) levels were not changed in the tumors (Fig. 6a). In terms of lysophosphatidylethanolamine (LPE) levels, saturated LPE was unaltered while MU-LPE levels declined in the tumor tissues (Fig. 6b, c). Besides, PE-plasmalogen levels were similar in tumor and non-tumor tissues (Fig. 6d).

Correlation of PU-TG species with tumor number

Total TG, DG and CE concentrations were induced in the tumors (Figs. 1a and e and 3a). These lipid classes did not correlate with the number of tumors in the liver (Table 3). MU-PS, MU-PI and MU-LPE levels were also changed in the tumors (Figs. 5e and f and 6c). Again, these lipids did not correlate with tumor number. This also applied to ceramide and SM levels (Table 3).

The nearly significant correlation of TGs with tumor number (Table 3) prompted more detailed analysis. There were indeed significant positive correlations of the PU-TG species with 6 and 8 double bonds and tumor number (Table 3).

The tumor suppressors p53 is induced and the antioxidant enzyme MnSOD is reduced in the tumor tissues

The tumor suppressor protein p53 was increased in the murine tumors (Fig. 7a, b). One of the downstream targets of p53 is manganese superoxide dismutase (MnSOD) [62]. MnSOD protein was low in the HCC tissues (Fig. 7a, c). Mutant p53 causes a shift from C38 to C36 and C34 PI species [63]. This was not observed in the murine tumors (Fig. 7d - f).

Hepatic expression of p53 and MnSOD and hepatic PI species related to p53 mutations in the normal tissues (NT) and tumor tissues (TT) of mice injected with diethylnitrosamine. a Expression of p53 and MnSOD. b Quantification of p53 (n = 5–6). c Quantification of MnSOD (n = 11–12). d PIs with 34 carbon atoms (n = 10–12). e PIs with 36 carbon atoms (n = 10 − 12). f PIs with 38 carbon atoms (n = 10–12). * P < 0.05, ** P < 0.01

Discussion

Lipids play a fundamental role in the development and progression of HCCs [5, 7, 26]. DEN is a widely used chemical to induce HCC in rodents [40], and here, lipid profiling was performed on normal and cancer tissues. As shown in humans [5], TGs and DGs accumulated in the murine liver tumors. In contrast to human HCCs [7] key enzymes of de novo lipogenesis were not induced in the murine liver cancers. Of note, ceramides were increased in the murine tumors while a decline was noticed in human HCC tissues [5, 33]. Thus, the DEN-HCC model is not appropriate for testing novel drugs targeting de novo lipogenesis or ceramide metabolism [7, 33].

The main responsible transcription factor for de novo lipogenesis is SREBP1c, and FAS, ACC and SCD1 were induced in human liver cancer [4, 6, 64]. In contrast, an upregulation of these enzymes was not observed in the murine tumors. Likewise, DGAT1 and DGAT2 are frequently overexpressed in many cancers [65] while being unchanged in the murine liver tumors.

ACC is inactivated upon phosphorylation by AMPK, which induces catabolic pathways while blocking energy-consuming processes. AMPK is activated by AMP and by phosphorylation [66] and is supposed to exert tumor suppressive functions in HCC [67]. Levels of phosphorylated ACC and AMPK did not change in the tumors arguing against a critical role of these enzymes for the tumor-specific lipidome.

LPL is a further enzyme described to be high in human HCCs [9]. LPL enhances the uptake of fatty acids by tumor cells, and suppression of LPL reinforces the effect of FAS blockage on cell proliferation [9]. High expression of the fatty acid translocase CD36 in human HCC further supports a role for exogenous fatty acid uptake in HCC [68]. In fact, LPL and CD36 were even downregulated in the murine tumors. This largely excludes exogenous fatty acids as a source of cellular triglyceride accumulation in the tumors.

A decline of PGC1alpha was noted in the HCC tissues of the DEN injected mice. PGC1alpha increases mitochondrial biogenesis and enhances fatty acid oxidation [13, 21]. Low PGC1alpha in the murine tumors may contribute to lower TG deposition in the tissues. Besides, CPT2 mRNA levels were found reduced in the tumors. Expression of additional genes participating in fatty acid oxidation was not downregulated in the tumors. To prove the suggestion that fatty acid oxidation is impaired in the murine liver cancer tissues, functional analysis of fatty acid oxidation is required, which was not performed in the present study.

Notably, PGC1alpha suppressed ApoB expression in hepatocytes [13], and high ApoB protein in the rodent tumors may be related to low expression of PGC1alpha. PGC1alpha further enhances hepatocyte nuclear factor 4alpha-dependent activation of the LIPC promoter [69].

Deficiency of LIPC contributes to liver steatosis [70] and LIPC was indeed reduced in the murine tumors. Protein levels of a further lipase – HSL – were, however, not changed in the tumors.

PGC1alpha mRNA expression did not decline in parallel with protein levels proposing the involvement of post-transcriptional mechanisms. The tumor suppressor protein p53 decreases the stability of PGC1alpha [71], and high expression of p53 in HCC tissues may contribute to downregulation of PGC1alpha protein.

The carcinogen DEN is well described to upregulate p53 protein in the liver [72, 73]. Much less is known about an additional induction of p53 in the rodent HCC tissues. In mice and rats, p53 RNA was about 1.5 to 2-fold higher in the tumor tissues [74, 75]. The p53 protein was also increased in the HCC tissues of mice with non-alcoholic stesatohepatitis [43]. Accordingly, p53 protein was higher in the tumors of the mice studied herein.

One of the multiple functions of p53 is the regulation of MnSOD activity, an important mitochondrial antioxidant [62]. MnSOD was downregulated in the murine liver tumors and this was described in human HCC [76]. MnSOD is additionally regulated by PGC1 alpha, which is a potent inducer of this enzyme [16].

Strongly increased de novo lipogenesis in human HCCs causes an enrichment of saturated and MU-lipids at the expense of PU-lipids [24, 25]. Such a shift was not observed in the DEN-model. There was a modest change of relatively low abundant MU-lipids, and MU-PS decreased whereas MU-PI increased in the tumors. Hall et al. reported on a decline of PU-PC species in the murine tumors of DEN-injected mice [61], and three of the 12 examined PU-PC species were reduced in the tumors analysed herein. The observed upregulation of MU-PCs in murine and human HCCs [61] could not be confirmed in the present investigation. This recent study used C57BL/6 mice [61] whereas C3H/HeNRj mice were analyzed in the current investigation. Different mouse strains exhibit variations in their liver lipidome and in their response to diets [77]. In addition, the lipidome can be affected by age, gender, and circadian rhythm [78]. Comparative studies are needed to identify the links between the tumor lipidome, genetic and environmental traits.

Positive correlations between the degree of TG saturation and disease severity existed in human HCCs [25]. In contrast, a positive relationship of tumor number and PU-TG levels was noticed in the murine model. This suggests that PU rather than saturated or MU-TGs contribute to tumor growth in the mouse model.

The regulation of phospholipids in HCC tissues has not been finally clarified. It is likely that PU-species are lower in the tumors, and a decline of PC and PE levels was also described [79,80,81]. Of note, PE-plasmalogens were low in HCC tissues of patients and this may contribute to oxidative stress [5, 80, 82]. In the DEN model, none of the analysed phospholipid classes were largely changed in the tumors. This applied to PC, PE, PS, PI, LPE, LPC and PE-plasmalogen lipids. Mutant p53 was shown to affect PI acyl chain composition and to increase species with shorter-chain fatty acids [63]. A shift in PI species fatty acid length did neither occur in human HCC tissues [24] nor in the murine tumors.

Cholesterol enhances cell proliferation, and was induced in human HCC tissues [5]. Similar to the DEN model, CEs accumulated in the human tumor tissues whereas free cholesterol levels did not change [24]. The pathways contributing to cholesterol deposition in human HCCs differ between the patients. SREBP2 is the main transcription factor regulating cholesterol homeostasis and was activated in the tumors of some patients [5]. SREBP2 and the apolipoproteins E and AII, which both have a role in cholesterol efflux [83], were not changed in the murine cancer tissues. Here, as has been also described in human HCCs [32], LDL-receptor protein was increased. In the murine liver, LDL-R mRNA was not regulated in parallel indicating the involvement of post-transcriptional mechanisms. PCSK9 induces the degradation of the LDL-receptor and low PCSK9 expression in human HCCs is in agreement with higher LDL-receptor protein [32]. In contrast to human HCCs, PCSK9 protein was not suppressed in the murine tumors. The underlying pathways contributing to increased LDL-receptor protein in the HCC tissues despite an accumulation of CEs have still to be defined. Thus, higher expression of the LDL-receptor may contribute to cholesterol accumulation in murine and human tumors.

Long-chain ceramides induce cell death and very long-chain species have the opposite effect [5, 34]. Unexpectedly, most of the ceramide species were induced in the murine tumors, and the long-chain / very long-chain ceramide ratio was increased. The decline of SMs in the murine tumors reveals an involvement of sphingomyelinases [5, 84]. In strong contrast to the murine situation, in most human HCC tissues ceramide levels are low while SM concentrations increase [5, 26, 85]. Thus the animal model described herein may be used to study the molecular adaption of liver tumor cells, which succeed to survive and proliferate despite high endogenous ceramide levels.

HCCs are heterogeneous tumors and disease etiology may affect tumor-associated lipid composition [85]. DEN-injected C3H/HeNRj mice fed a low methionine, choline-deficient diet were used to study HCC development in non-alcoholic steatohepatitis. Notably, de novo lipogenesis was suppressed in these tumors and levels of TGs and DGs were low [43]. Various murine HCC models were established [40] and lipidomic profiling will give further insights into the role of dysregulated lipid metabolism in cancer development and progression.

Study strengths and limitations

The strength of this study was the comprehensive analysis of the cancer associated lipid composition in the widely used DEN model. Expression of several proteins with a role in lipid metabolism was analysed in parallel. Limitation is that only male C3H/HeNRj mice fed a standard chow were studied. Comparison of mouse strains or mice fed different diets was not performed. Besides, fatty acid synthesis, oxidation and uptake by the tumors were not quantified.

Conclusions

The DEN injected mice had higher TG levels in the tumors as was reported in human HCCs. De novo lipogenesis did not increase in parallel, and a shift from PU to saturated lipids was not observed. Thus, anti-HCC drugs targeting FAS or ACC may not be effective in this model. Ceramides did not decline in the tumors, but were rather induced. The model described herein is thus suitable to identify the molecular changes allowing hepatocyte proliferation when cellular ceramides are increased. This may be relevant for the development of anticancer drugs targeting the sphingolipid pathways.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets generated and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on request.

Abbreviations

- ACC:

-

Acetyl-CoA-carboxylase

- AMPK:

-

AMP-activated protein kinase

- Apo:

-

Apolipoprotein

- CE:

-

Cholesteryl ester

- DG:

-

Diglycerides

- DGAT:

-

Diacylglycerol-O-acyltransferase

- FAS:

-

Fatty Acid Synthase

- HSL:

-

Hormone sensitive lipase

- LIPC:

-

Hepatic lipase

- LPL:

-

Lipoprotein Lipase

- LDL:

-

Low density lipoprotein

- LPC:

-

Lysophosphatidylcholine

- LPE:

-

Lysophosphatidylethanolamine

- MnSOD:

-

Manganese Superoxide Dismutase

- PC:

-

Phosphatidylcholine

- PCSK9:

-

Proprotein convertase subtilisin/kexin type 9

- PE-P:

-

PE-plasmalogen

- PE:

-

Phosphatidylethanolamine

- PGC1alpha:

-

Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma coactivator 1 alpha

- PI:

-

Phosphatidylinositol

- PS:

-

Phosphatidylserine

- SM:

-

Sphingomyelin

- TG:

-

Triglycerides

References

Dai CY, Lin CY, Tsai PC, Lin PY, Yeh ML, Huang CF, Chang WT, Huang JF, Yu ML, Chen YL. Impact of tumor size on the prognosis of hepatocellular carcinoma in patients who underwent liver resection. J Chin Med Assoc. 2018;81:155–63.

Gallicchio R, Nardelli A, Mainenti P, Nappi A, Capacchione D, Simeon V, Sirignano C, Abbruzzi F, Barbato F, Landriscina M, Storto G. Therapeutic strategies in HCC: radiation modalities. Biomed Res Int. 2016;2016:1295329.

Singal AG, Lampertico P, Nahon P. Epidemiology and surveillance for hepatocellular carcinoma. New trends J Hepatol. 2020;72:250–61.

Berndt N, Eckstein J, Heucke N, Gajowski R, Stockmann M, Meierhofer D, Holzhutter HG. Characterization of lipid and lipid droplet metabolism in human HCC. Cells 2019;8:512.

Buechler C, Aslanidis C. Role of lipids in pathophysiology, diagnosis and therapy of hepatocellular carcinoma. Biochim Biophys Acta Mol Cell Biol Lipids. 2020;1865:158658.

Calvisi DF, Wang C, Ho C, Ladu S, Lee SA, Mattu S, Destefanis G, Delogu S, Zimmermann A, Ericsson J, et al. Increased lipogenesis, induced by AKT-mTORC1-RPS6 signaling, promotes development of human hepatocellular carcinoma. Gastroenterology. 2011;140:1071–83.

Che L, Paliogiannis P, Cigliano A, Pilo MG, Chen X, Calvisi DF. Pathogenetic, prognostic, and therapeutic role of fatty acid synthase in human hepatocellular carcinoma. Front Oncol. 2019;9:1412.

Che L, Pilo MG, Cigliano A, Latte G, Simile MM, Ribback S, Dombrowski F, Evert M, Chen X, Calvisi DF. Oncogene dependent requirement of fatty acid synthase in hepatocellular carcinoma. Cell Cycle. 2017;16:499–507.

Cao D, Song X, Che L, Li X, Pilo MG, Vidili G, Porcu A, Solinas A, Cigliano A, Pes GM, et al. Both de novo synthetized and exogenous fatty acids support the growth of hepatocellular carcinoma cells. Liver Int. 2017;37:80–9.

Che L, Chi W, Qiao Y, Zhang J, Song X, Liu Y, Li L, Jia J, Pilo MG, Wang J, et al. Cholesterol biosynthesis supports the growth of hepatocarcinoma lesions depleted of fatty acid synthase in mice and humans. Gut. 2020;69:177–86.

Hu J, Che L, Li L, Pilo MG, Cigliano A, Ribback S, Li X, Latte G, Mela M, Evert M, et al. Co-activation of AKT and c-Met triggers rapid hepatocellular carcinoma development via the mTORC1/FASN pathway in mice. Sci Rep. 2016;6:20484.

Li L, Pilo GM, Li X, Cigliano A, Latte G, Che L, Joseph C, Mela M, Wang C, Jiang L, et al. Inactivation of fatty acid synthase impairs hepatocarcinogenesis driven by AKT in mice and humans. J Hepatol. 2016;64:333–41.

Morris EM, Meers GM, Booth FW, Fritsche KL, Hardin CD, Thyfault JP, Ibdah JA. PGC-1alpha overexpression results in increased hepatic fatty acid oxidation with reduced triacylglycerol accumulation and secretion. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2012;303:G979-92.

Chen J, Gingold JA, Su X. Immunomodulatory TGF-beta signaling in hepatocellular carcinoma. Trends Mol Med. 2019;25:1010–23.

Desterke C, Chiappini F. Lipid related genes altered in NASH connect inflammation in liver pathogenesis progression to HCC: a canonical pathway. Int J Mol Sci 2019;20:5594.

Wang C, Dong L, Li X, Li Y, Zhang B, Wu H, Shen B, Ma P, Li Z, Xu Y, et al. The PGC1alpha/NRF1-MPC1 axis suppresses tumor progression and enhances the sensitivity to sorafenib/doxorubicin treatment in hepatocellular carcinoma. Free Radic Biol Med. 2021;163:141–52.

Huang S, Rutkowsky JM, Snodgrass RG, Ono-Moore KD, Schneider DA, Newman JW, Adams SH, Hwang DH. Saturated fatty acids activate TLR-mediated proinflammatory signaling pathways. J Lipid Res. 2012;53:2002–13.

Day CP. From fat to inflammation. Gastroenterology. 2006;130:207–10.

Schaeffler A, Gross P, Buettner R, Bollheimer C, Buechler C, Neumeier M, Kopp A, Schoelmerich J, Falk W. Fatty acid-induced induction of Toll-like receptor-4/nuclear factor-kappaB pathway in adipocytes links nutritional signalling with innate immunity. Immunology. 2009;126:233–45.

Schaffler A, Scholmerich J, Buchler C. Mechanisms of disease: adipocytokines and visceral adipose tissue–emerging role in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Nat Clin Pract Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2005;2:273–80.

Rius-Perez S, Torres-Cuevas I, Millan I, Ortega AL, Perez S. PGC-1alpha, inflammation, and oxidative stress: an integrative view in metabolism. Oxid Med Cell Longev. 2020;2020:1452696.

Bibbo S, Ianiro G, Dore MP, Simonelli C, Newton EE, Cammarota G. Gut microbiota as a driver of inflammation in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Mediators Inflamm. 2018;2018:9321643.

Huang Q, Tan Y, Yin P, Ye G, Gao P, Lu X, Wang H, Xu G. Metabolic characterization of hepatocellular carcinoma using nontargeted tissue metabolomics. Cancer Res. 2013;73:4992–5002.

Krautbauer S, Meier EM, Rein-Fischboeck L, Pohl R, Weiss TS, Sigruener A, Aslanidis C, Liebisch G, Buechler C. Ceramide and polyunsaturated phospholipids are strongly reduced in human hepatocellular carcinoma. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2016;1861:1767–74.

Li Z, Guan M, Lin Y, Cui X, Zhang Y, Zhao Z, Zhu J. Aberrant lipid metabolism in hepatocellular carcinoma revealed by liver lipidomics. Int J Mol Sci. 2017;18:2550.

Ismail IT, Elfert A, Helal M, Salama I, El-Said H, Fiehn O. Remodeling lipids in the transition from chronic liver disease to hepatocellular carcinoma. Cancers (Basel). 2020;13:88.

Eggens I, Ekstrom TJ, Aberg F. Studies on the biosynthesis of polyisoprenols, cholesterol and ubiquinone in highly differentiated human hepatomas. J Exp Pathol (Oxford). 1990;71:219–32.

Liu Y, Guo X, Wu L, Yang M, Li Z, Gao Y, Liu S, Zhou G, Zhao J. Lipid rafts promote liver cancer cell proliferation and migration by up-regulation of TLR7 expression. Oncotarget. 2016;7:63856–69.

Horton JD. Sterol regulatory element-binding proteins: transcriptional activators of lipid synthesis. Biochem Soc Trans. 2002;30:1091–5.

Xue L, Qi H, Zhang H, Ding L, Huang Q, Zhao D, Wu BJ, Li X. Targeting SREBP-2-regulated mevalonate metabolism for cancer therapy. Front Oncol. 2020;10:1510.

Shapiro MD, Tavori H, Fazio S. PCSK9: From basic science discoveries to clinical trials. Circ Res. 2018;122:1420–38.

Bhat M, Skill N, Marcus V, Deschenes M, Tan X, Bouteaud J, Negi S, Awan Z, Aikin R, Kwan J, et al. Decreased PCSK9 expression in human hepatocellular carcinoma. BMC Gastroenterol. 2015;15:176.

Grbcic P, Car EPM, Sedic M. Targeting ceramide metabolism in hepatocellular carcinoma: new points for therapeutic intervention. Curr Med Chem. 2020;27:6611–27.

Montgomery MK, Brown SH, Lim XY, Fiveash CE, Osborne B, Bentley NL, Braude JP, Mitchell TW, Coster AC, Don AS, et al. Regulation of glucose homeostasis and insulin action by ceramide acyl-chain length: a beneficial role for very long-chain sphingolipid species. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2016;1861:1828–39.

Moro K, Nagahashi M, Gabriel E, Takabe K, Wakai T. Clinical application of ceramide in cancer treatment. Breast Cancer. 2019;26:407–15.

Li G, Liu D, Kimchi ET, Kaifi JT, Qi X, Manjunath Y, Liu X, Deering T, Avella DM, Fox T, et al. Nanoliposome C6-ceramide increases the anti-tumor immune response and slows growth of liver tumors in mice. Gastroenterology. 2018;154:1024-36 e9.

Lv H, Zhang Z, Wu X, Wang Y, Li C, Gong W, Gui L, Wang X. Preclinical evaluation of liposomal C8 ceramide as a potent anti-hepatocellular carcinoma agent. PLoS One. 2016;11:e0145195.

Tagaram HR, Divittore NA, Barth BM, Kaiser JM, Avella D, Kimchi ET, Jiang Y, Isom HC, Kester M, Staveley-O’Carroll KF. Nanoliposomal ceramide prevents in vivo growth of hepatocellular carcinoma. Gut. 2011;60:695–701.

Garattini S, Grignaschi G. Animal testing is still the best way to find new treatments for patients. Eur J Intern Med. 2017;39:32–5.

Bakiri L, Wagner EF. Mouse models for liver cancer. Mol Oncol. 2013;7:206–23.

Alkhouri N, Dixon LJ, Feldstein AE. Lipotoxicity in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: not all lipids are created equal. Expert Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2009;3:445–51.

Vance JE, Tasseva G. Formation and function of phosphatidylserine and phosphatidylethanolamine in mammalian cells. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2013;1831:543–54.

Haberl EM, Pohl R, Rein-Fischboeck L, Horing M, Krautbauer S, Liebisch G, Buechler C. Hepatic lipid profile in mice fed a choline-deficient, low-methionine diet resembles human non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. Lipids Health Dis. 2020;19:250.

Haberl EM, Pohl R, Rein-Fischboeck L, Feder S, Sinal CJ, Bruckmann A, Hoering M, Krautbauer S, Liebisch G, Buechler C. Overexpression of hepatocyte chemerin-156 lowers tumor burden in a murine model of diethylnitrosamine-induced hepatocellular carcinoma. Int J Mol Sci 2019;21:252.

Salmon F, Grosios K, Petry H. Safety profile of recombinant adeno-associated viral vectors: focus on alipogene tiparvovec (Glybera(R)). Expert Rev Clin Pharmacol. 2014;7:53–65.

Carestia A, Kim SJ, Horling F, Rottensteiner H, Lubich C, Reipert BM, Crowe BA, Jenne CN. Modulation of the liver immune microenvironment by the adeno-associated virus serotype 8 gene therapy vector. Mol Ther Methods Clin Dev. 2021;20:95–108.

Hubrecht RC, Carter E. The 3Rs and humane experimental technique: implementing change. Animals (Basel) 2019;9:754.

Bligh EG, Dyer WJ. A rapid method of total lipid extraction and purification. Can J Biochem Physiol. 1959;37:911–7.

Liebisch G, Binder M, Schifferer R, Langmann T, Schulz B, Schmitz G. High throughput quantification of cholesterol and cholesteryl ester by electrospray ionization tandem mass spectrometry (ESI-MS/MS). Biochim Biophys Acta. 2006;1761:121–8.

Liebisch G, Drobnik W, Lieser B, Schmitz G. High-throughput quantification of lysophosphatidylcholine by electrospray ionization tandem mass spectrometry. Clin Chem. 2002;48:2217–24.

Liebisch G, Drobnik W, Reil M, Trumbach B, Arnecke R, Olgemoller B, Roscher A, Schmitz G. Quantitative measurement of different ceramide species from crude cellular extracts by electrospray ionization tandem mass spectrometry (ESI-MS/MS). J Lipid Res. 1999;40:1539–46.

Liebisch G, Lieser B, Rathenberg J, Drobnik W, Schmitz G. High-throughput quantification of phosphatidylcholine and sphingomyelin by electrospray ionization tandem mass spectrometry coupled with isotope correction algorithm. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2004;1686:108–17.

Matyash V, Liebisch G, Kurzchalia TV, Shevchenko A, Schwudke D. Lipid extraction by methyl-tert-butyl ether for high-throughput lipidomics. J Lipid Res. 2008;49:1137–46.

Horing M, Ejsing CS, Hermansson M, Liebisch G. Quantification of cholesterol and cholesteryl ester by direct flow injection high-resolution fourier transform mass spectrometry utilizing species-specific response factors. Anal Chem. 2019;91:3459–66.

Husen P, Tarasov K, Katafiasz M, Sokol E, Vogt J, Baumgart J, Nitsch R, Ekroos K, Ejsing CS. Analysis of lipid experiments (ALEX): a software framework for analysis of high-resolution shotgun lipidomics data. PLoS One. 2013;8:e79736.

Horing M, Ekroos K, Baker PRS, Connell L, Stadler SC, Burkhardt R, Liebisch G. Correction of isobaric overlap resulting from sodiated ions in lipidomics. Anal Chem. 2020;92:10966–70.

Liebisch G, Vizcaino JA, Kofeler H, Trotzmuller M, Griffiths WJ, Schmitz G, Spener F, Wakelam MJ. Shorthand notation for lipid structures derived from mass spectrometry. J Lipid Res. 2013;54:1523–30.

Haberl EM, Pohl R, Rein-Fischboeck L, Feder S, Sinal CJ, Buechler C. Chemerin in a mouse model of non-alcoholic steatohepatitis and hepatocarcinogenesis. Anticancer Res. 2018;38:2649–57.

Kim KI, Park JH, Lee YJ, Lee TS, Park JJ, Song I, Nahm SS, Cheon GJ, Lim SM, Chung JK, Kang JH. In vivo bioluminescent imaging of alpha-fetoprotein-producing hepatocellular carcinoma in the diethylnitrosamine-treated mouse using recombinant adenoviral vector. J Gene Med. 2012;14:513–20.

Schneider CA, Rasband WS, Eliceiri KW. NIH Image to ImageJ: 25 years of image analysis. Nat Methods. 2012;9:671–5.

Hall Z, Chiarugi D, Charidemou E, Leslie J, Scott E, Pellegrinet L, Allison M, Mocciaro G, Anstee QM, Evan GI, et al. Lipid remodeling in hepatocyte proliferation hepatocellular carcinoma hepatology. 2021;73:1028–44.

Hussain SP, Amstad P, He P, Robles A, Lupold S, Kaneko I, Ichimiya M, Sengupta S, Mechanic L, Okamura S, et al. p53-induced up-regulation of MnSOD and GPx but not catalase increases oxidative stress and apoptosis. Cancer Res. 2004;64:2350–6.

Naguib A, Bencze G, Engle DD, Chio II, Herzka T, Watrud K, Bencze S, Tuveson DA, Pappin DJ, Trotman LC. p53 mutations change phosphatidylinositol acyl chain composition. Cell Rep. 2015;10:8–19.

De Matteis S, Ragusa A, Marisi G, De Domenico S, Casadei Gardini A, Bonafe M, Giudetti AM. Aberrant metabolism in hepatocellular carcinoma provides diagnostic and therapeutic opportunities. Oxid Med Cell Longev. 2018;2018:7512159.

Hernandez-Corbacho MJ, Obeid LM. A novel role for DGATs in cancer. Adv Biol Regul. 2019;72:89–101.

Viollet B, Foretz M, Guigas B, Horman S, Dentin R, Bertrand L, Hue L, Andreelli F. Activation of AMP-activated protein kinase in the liver: a new strategy for the management of metabolic hepatic disorders. J Physiol. 2006;574:41–53.

Yang X, Liu Y, Li M, Wu H, Wang Y, You Y, Li P, Ding X, Liu C, Gong J. Predictive and preventive significance of AMPK activation on hepatocarcinogenesis in patients with liver cirrhosis. Cell Death Dis. 2018;9:264.

Luo X, Zheng E, Wei L, Zeng H, Qin H, Zhang X, Liao M, Chen L, Zhao L, Ruan XZ, et al. The fatty acid receptor CD36 promotes HCC progression through activating Src/PI3K/AKT axis-dependent aerobic glycolysis. Cell Death Dis. 2021;12:328.

Rufibach LE, Duncan SA, Battle M, Deeb SS. Transcriptional regulation of the human hepatic lipase (LIPC) gene promoter. J Lipid Res. 2006;47:1463–77.

Andres-Blasco I, Herrero-Cervera A, Vinue A, Martinez-Hervas S, Piqueras L, Sanz MJ, Burks DJ, Gonzalez-Navarro H. Hepatic lipase deficiency produces glucose intolerance, inflammation and hepatic steatosis. J Endocrinol. 2015;227:179–91.

Deng X, Li Y, Gu S, Chen Y, Yu B, Su J, Sun L, Liu Y. p53 affects PGC1alpha stability through AKT/GSK-3beta to enhance cisplatin sensitivity in non-Small. Cell Lung Cancer Front Oncol. 2020;10:1252.

Chen CC, Kim KH, Lau LF. The matricellular protein CCN1 suppresses hepatocarcinogenesis by inhibiting compensatory proliferation. Oncogene. 2016;35:1314–23.

Zhang Z, Chen C, Wang G, Yang Z, San J, Zheng J, Li Q, Luo X, Hu Q, Li Z, Wang D. Aberrant expression of the p53-inducible antiproliferative gene BTG2 in hepatocellular carcinoma is associated with overexpression of the cell cycle-related proteins. Cell Biochem Biophys. 2011;61:83–91.

De Miglio MR, Muroni MR, Simile MM, Calvisi DF, Tolu P, Deiana L, Carru A, Bonelli G, Feo F, Pascale RM. Implication of Bcl-2 family genes in basal and D-amphetamine-induced apoptosis in preneoplastic and neoplastic rat liver lesions. Hepatology. 2000;31:956–65.

Shi SY, Luk CT, Schroer SA, Kim MJ, Dodington DW, Sivasubramaniyam T, Lin L, Cai EP, Lu SY, Wagner KU, et al. Janus Kinase 2 (JAK2) dissociates hepatosteatosis from hepatocellular carcinoma in mice. J Biol Chem. 2017;292:3789–99.

Wang R, Yin C, Li XX, Yang XZ, Yang Y, Zhang MY, Wang HY, Zheng XF. Reduced SOD2 expression is associated with mortality of hepatocellular carcinoma patients in a mutant p53-dependent manner. Aging. 2016;8:1184–200.

Norheim F, Chella Krishnan K, Bjellaas T, Vergnes L, Pan C, Parks BW, Meng Y, Lang J, Ward JA, Reue K, et al. Genetic regulation of liver lipids in a mouse model of insulin resistance and hepatic steatosis. Mol Syst Biol. 2021;17:e9684.

Ten Hove M, Pater L, Storm G, Weiskirchen S, Weiskirchen R, Lammers T, Bansal R. The hepatic lipidome: from basic science to clinical translation. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2020;159:180–97.

Abel S, De Kock M, van Schalkwyk DJ, Swanevelder S, Kew MC, Gelderblom WC. Altered lipid profile, oxidative status and hepatitis B virus interactions in human hepatocellular carcinoma. Prostaglandins Leukot Essent Fatty Acids. 2009;81:391–9.

Liu Z, Zhang Z, Mei H, Mao J, Zhou X. Distribution and clinical relevance of phospholipids in hepatocellular carcinoma. Hepatol Int. 2020;14:544–55.

Morita Y, Sakaguchi T, Ikegami K, Goto-Inoue N, Hayasaka T, Hang VT, Tanaka H, Harada T, Shibasaki Y, Suzuki A, et al. Lysophosphatidylcholine acyltransferase 1 altered phospholipid composition and regulated hepatoma progression. J Hepatol. 2013;59:292–9.

Lu Y, Chen J, Huang C, Li N, Zou L, Chia SE, Chen S, Yu K, Ling Q, Cheng Q, et al. Comparison of hepatic and serum lipid signatures in hepatocellular carcinoma patients leads to the discovery of diagnostic and prognostic biomarkers. Oncotarget. 2018;9:5032–43.

Kawashiri MA, Maugeais C, Rader DJ. High-density lipoprotein metabolism: molecular targets for new therapies for atherosclerosis. Curr Atheroscler Rep. 2000;2:363–72.

Morales A, Mari M, Garcia-Ruiz C, Colell A, Fernandez-Checa JC. Hepatocarcinogenesis and ceramide/cholesterol metabolism. Anticancer Agents Med Chem. 2012;12:364–75.

Haberl EM, Weiss TS, Peschel G, Weigand K, Köhler N, Pauling JK, Wenzel JJ, Höring M, Krautbauer S, Liebisch G, Buechler C. Liver lipids of patients with hepatitis B and C and associated hepatocellular carcinoma. Int J Mol Sci. 2021;22:5297.

Acknowledgements

The expert technical assistance of Jolanthe Aiwanger, Simone Düchtel, Doreen Müller and Elena Underberg is greatly appreciated.

Funding

This work was supported by funds from the German Research Foundation (BU1141/13 − 1). Open Access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

CB designed and supervised this study; EMH, RP, LRF, SK, and MH performed experiments; GL supervised lipidomic analysis; EMH, RP, LRF, SK, MH, GL and CB analyzed data; CB wrote the paper. All the authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Animal experiments complied with the German Law on Animal Protection and the Institute for Laboratory Animal Research Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals under approval number 54-2532.1-21/14. Experiments were in accordance with the institutional and governmental regulations for animal use.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1: Supplementary Figure 1.

Expression of SREBPs and SCD1 and median values of CEs and phospholipids in the normal tissues (NT) and tumor tissues (TT) of mice injected with diethylnitrosamine. a Expression of SREBP1c precursor and active form and SCD1. b Hepatic cholesteryl ester (CE) species and free cholesterol (FC). c Expression of SREBP2 precursor and active form. d Median levels of PS and PI in TT and NT. e Median levels of saturated (sat), MU-PC and PU-PC in NT and TT. ** P < 0.01.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Haberl, E.M., Pohl, R., Rein-Fischboeck, L. et al. Accumulation of cholesterol, triglycerides and ceramides in hepatocellular carcinomas of diethylnitrosamine injected mice. Lipids Health Dis 20, 135 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12944-021-01567-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12944-021-01567-w