Abstract

Background

Trial of Labor After Cesarean is an important strategy for reducing the overall rate of cesarean delivery. Offering the option of vaginal delivery to a woman with a history of cesarean section requires the ability to manage a potential uterine rupture quickly and effectively. This requires infrastructure and organization of the maternity unit so that the decision-to-delivery interval is as short as possible when uterine rupture is suspected. We hypothesize that the organizational characteristics of maternity units in Belgium have an impact on their proposal and success rates of trial of labour after cesarean section.

Methods

We collected data on the organizational characteristics of Belgian maternity units using an online questionnaire. Data on the frequency of cesarean section, trial of labor and vaginal birth after cesarean section were obtained from regional perinatal registries. We analyzed the determinants of the proposal and success of trial of labor after cesarean section and report the associations as mean proportions.

Results

Of the 101 maternity units contacted, 97 responded to the questionnaire and data from 95 was included in the analysis. Continuous on-site presence of a gynecologist and an anesthetist was associated with a higher proportion of trial of labor after cesarean section, compared to units where staff was on-call from home (51% versus 46%, p = 0.04). There is a non-significant trend towards more trial of labor after cesarean section in units with an operating room in or near the delivery unit and a shorter transfer time, in larger units (> 1500 deliveries/year) and in units with a neonatal intensive care unit. The proposal of trial of labor after cesarean section and its success was negatively correlated to the number of cesarean section in the maternity unit (Spearman’ rho = 0.50 and 0.42, p value < 0.001).

Conclusions

Organizational differences in maternity units appear to affect the proposal of trial of labor after cesarean section. Addressing these organizational factors may not be sufficient to change practice, given that general tendency to perform a cesarean section in the maternity unit is the main contributor to the percentage of trial of labor after cesarean.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

The projections for cesarean section (CS) rates globally are worrisome. It is estimated that 28.5% of women will give birth by CS by 2030 worldwide [1]. In Europe, overall CS rates have remained stable between 2015 and 2019, but vary considerably between countries (16.4% in Finland and 53.1% in Cyprus) [2]. Overuse of CS has been shown to have no additional benefit in reducing maternal or neonatal risks, and increases the costs and the risks to future fertility, pregnancies and health of the children [3, 4]. In Belgium, the CS rate is increasing, with regional rates in 2021 of 22.4%, 20.1% and 22.1% in Wallonia, Brussels and Flanders, respectively [5,6,7]. The proportion of women with a history of CS was 68.9%, 70.9% and 70.2% of all multiparous women who had a CS in 2021 in Wallonia, Brussels and Flanders, respectively [5,6,7]. There is a considerable variation in CS rates between maternity units, ranging from 14.2% to 35.3% in 2021 [5,6,7].

Avoiding the first CS would have the greatest impact on limiting the increase in the CS rate. Another important strategy is to offer women with a history of CS the opportunity to attempt a Trial of Labor After Cesarean (TOLAC) [8, 9]. TOLAC, compared to Elective Repeat Cesarean Section (ERCS), reduces the risks associated with CS in the index and future pregnancies, but carries the risk of uterine rupture, with the associated severe morbidity and mortality [10]. Therefore, TOLAC implies the need for rapid management in case of a suspected uterine rupture. In addition, a CS performed during labor because of failed TOLAC, exposes the mother to more complications than a planned ERCS. When counseling women with a history of CS, obstetricians will weigh the benefits of a successful VBAC against the risks of a failed TOLAC or uterine rupture. The organizational characteristics of the labor and delivery unit are determinants of the speed and safety with which emergency CS can be performed, and can play an important role in the informed decision making process regarding mode of delivery and management during labor in women with a history of CS [11,12,13,14,15].

The estimated TOLAC rate in Belgium (47%) is low compared to other European countries [16]. In Belgium, maternity units are relatively small (ranging from 130 to 3400 deliveries in 2015–2017) [5,6,7]. We hypothesize that organizational characteristics, including the proximity to the operating room (OR) and the continuous on-site availability of medical staff, may have an impact on the offer of TOLAC and the management of a woman attempting TOLAC in the maternity unit.

Methods

Aim

The objective of this study was to assess the impact of organizational determinants on the provision and success of TOLAC in maternity units in Belgium.

Study design

We performed an ecological study, using data from 2015 to 2017.

Belgian setting

Belgium is divideded in three different regions from north to south: Flanders, Brussels and Wallonia. Perinatal data are analyzed at the regional level by the Centre for Perinatal Epidemiology for Flanders (Studiecentrum voor Perinatale Epidemiologie, SPE) and for Brussels and Wallonia (Centre d’Epidémiologie Périnatale, CEpiP). SPE and CEpiP collect data on a mandatory basis, covering almost 100% of births in Belgian maternity units and home births. A selected set of perinatal data is recorded by the obstetrician, midwife and neonatologist immediately after birth.

Study data

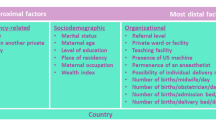

An online questionnaire using Research Electronic Data Capture (REDCap) at Ghent University Hospital and Brussels University Hospital was distributed to a contact person in each maternity unit [17, 18]. This questionnaire collected information on the availability of a gynecologist, anesthesiologist and pediatrician on-site 24/7, the presence of a neonatal intensive care unit (NICU) in the hospital, the location of the OR and the estimated transfer time from the delivery room to the OR in the event of an emergency CS. The answers to the questionnaire were linked to the data from each maternity unit obtained from the national perinatal databases, including total number of deliveries, total number of CS, number of ERCS, estimated number of TOLAC based on the number of successful vaginal births (VBAC), and number of unplanned repeat CS. Because the planned mode of delivery is not recorded in perinatal registries, the number of TOLAC was calculated as the sum of the number of VBAC and the number of unplanned repeat CS.

Statistical analysis

The unit of analysis was the maternity and the proportions of TOLAC and VBAC were treated as continuous variables, without weighting for the number of deliveries. We calculated a mean proportion of TOLAC for each category of the organizational variables. The statistical significance of the differences was assessed using a T-test, and by an ANOVA when there were more than two categories. We assessed the correlations between the proportions of TOLAC and VBAC in case of TOLAC, and the overall CS rate and the proportions of TOLAC and of VBAC using a Spearman correlation coefficient. We performed a multivariable linear regression analysis to evaluate the independent contribution of predictors to the proportion of TOLAC in the unit.

Results

A total of 101 maternity units were contacted and 97 completed the questionnaire. Two maternity units were excluded from the analysis because of missing data, one in the questionnaire and one in the obstetric report. Ninety-five maternity units were included in the analysis.

There were important organizational differences between larger maternity units with more than 1500 deliveries/year (n = 22) compared to smaller units (1500 or less deliveries/year) (n = 73), shown in Table 1. A greater proportion of large maternity units had the multidisciplinary medical staff on-site 24/7, a NICU, an OR in the delivery room or on the same floor and reported a shorter transfer time in case of emergency CS, compared with smaller units.

There was a small and not statistically significant difference in the overall percentage of CS performed between larger and smaller units (20.4% and 21.2%, respectively, p = 0.31). There was no difference according by unit size in the percentage of women with a history of CS (11%).

The estimated proportion of women who were offered a TOLAC was significantly higher in maternity units in the southern part of the country, compared to Flanders (p = 0.02), as shown in Table 2. The presence of a gynecologist and an anesthetist on site was associated with a higher proportion of TOLAC, compared to maternity units where both medical staff are on call from home (p = 0.04) (Table 2). The mean proportion of TOLAC is slightly higher when the maternity unit is larger, has a NICU, has an OR in or near the delivery unit and when the estimated transfer time is shorter, but these differences were not statistically significant (Table 2). The organizational variables were not associated with the overall proportion of CS in the maternity unit, or with the success of the TOLAC attempt (Additional Tables 1 and 2).

There was no correlation between the proportion of TOLAC and the overall success rate of TOLAC (Spearman’ rho = 0.06, p value = 0.57) (Fig. 1). However, there was a significant negative correlation between the overall proportion of CS in the unit and both the estimated offer of TOLAC (Spearman’ rho = 0.50, p value < 0.001) and its success (Spearman’ rho = 0.42, p value < 0.001) (Figs. 2 and 3).

Included in a linear multiple regression model, the variables associated in the univariable analysis showed that each percentage increase in the overall proportion of CS was associated with a 1.2% decrease in TOLAC (95%CI: 0.8 to 1.6%, p < 0.001), adjusted for the location of the unit and for the presence on-site of a gynecologist and an anesthesiologist on site. The region of the unit was associated with a 4.0% (95%CI: 0.9 to 7.0%, p = 0.01) difference in the rate of TOLAC. On-site medical staff presence 24/7 was associated with a 4.2% increase in TOLAC (95%CI: 0.6 to 7.0%, p = 0.02), compared with units where medical staff were on-call from home. There was no change in the estimates with adjustment, compared to the results in the univariable analysis, showing that the included variables are independent predictors of the proportion of TOLAC. Adding other organizational variables to the model did not add information because of important associations between maternity units characteristics.

Discussion

We found important differences between maternity units in the percentage of women with a history of CS who attempted a vaginal delivery. These differences were related to organizational factors, but also to the general tendency of the hospital to perform a CS.

Limitations of our study include the fact that the questionnaire was short to avoid overwhelming busy clinicians. In some units, the on-site gynecologist is a trainee who must wait for a senior colleague to perform a CS. We did not ask for this level of detail. In many maternity units in Belgium the CS room is located outside the delivery room, even on a different floor, especially in smaller hospitals. Nevertheless, most transfer times from the delivery room to the OR are reported to be less than five minutes. The responses to the questionnaire refer to the time it takes to reach the OR for an ambulatory person (e.g., obstetrician), rather than the duration of the patient’s transfer. However, these responses, indicate that most respondents are confident in their ability to quickly transfer the woman to the OR to perform an emergency CS. Another important limitation is the lack of data on the safety of attempted vaginal birth, and its relationship to organizational factors, as information on uterine rupture and asphyxia is not routinely recorded in the national registries. A final limitation is that the TOLAC rate is an overestimate of the true TOLAC rate, which is based on the sum of the number of VBACs and the number of unplanned repeat CS. Planned mode of delivery is not recorded in perinatal registries.

When discussing the mode of delivery with a woman with a history of CS, the obstetrician may be reluctant to offer a TOLAC if the labor and deliveryunit has less capacity to manage an emergency CS. Among the organizational differences, we chose to collect information and analyze factors that are likely to influence the decision-to-delivery interval. There is no consensus on the best decision-to-delivery interval, but it should be as short as possible in the event of complications during TOLAC [12,13,14,15, 19, 20]. This is the primary concern when offering a TOLAC, both for patient safety and from a medicolegal perspective. If uterine rupture is suspected, it is recommended to perform an emergency CS and deliver the baby within 30 min of the decision, which is not easy to achieve [12, 19]. Previous studies have shown that the transfer time to the OR and the lack of medical staff on site are the most important delaying factors [21,22,23,24].

A significant proportion of maternity units in Belgium have fewer than 1500 deliveries per year. In smaller units, it is more difficult to provide a permanent medical presence on site (especially the anesthesiologist and the obstetrician) and a dedicated OR in the delivery room. This calls into question the safety of TOLAC in smaller units, because of the risk of perinatal asphyxia and poor neonatal outcome in the event of uterine rupture. The recommendation in these situations should not be to perform more ERCS in women with a history of CS, but to have a medical presence on site when a woman with a CS scar is in labor and to alert the OR of a possible urgent CS. If these options are not realistic, referring patients with a CS scar and a desire for TOLAC to a larger unit could be an alternative strategy.

We found a statistically significant association between the presence of 24-h on-site medical staff, which is an important determinant of the ability to perform an emergency CS, and the mean proportion of TOLAC [25]. Previous studies have suggested that higher TOLAC and Vaginal Birth After C-section (VBAC) rates were associated with 24/7 on-site anesthesiologist presence, which was more likely in larger volume hospitals [26, 27]. A single-center study showed significantly higher TOLAC and VBAC rates when women were cared for by physicians ona night float call schedule compared with physicians on a ‘traditional’ schedule. Night float call was defined as a schedule in which the provider had clinical responsibility only for a day or night shift, with no other clinical responsibilities before or after the period of responsibility for laboring women [25].

The independent effect of the other organizational factors could not be assessed in a multivariable model, because of significant co-linearity between them (i.e., larger hospitals have a NICU, a readily accessible OR and on site medical staff).

We found no correlation between the provision of TOLAC and its success (VBAC), which may be partly explained by the overestimation of TOLAC. If anything, there was a small trend toward higher success with a higher proportion of TOLAC. There was a significant negative correlation between the overall proportion of CS and the proportion of TOLAC and in case of TOLAC, VBAC. This correlation was also reported at the country level in an international study of uterine rupture [16]. Countries with lower CS rates had higher rates of TOLAC and VBAC. We hypothesize that these associations are also present at the individual level. The TOLAC and VBAC rates may vary among obstetricians depending on their willingness to avoid CS, the type of obstetric practice and the case mix of the maternity unit. The level of involvement of midwives may also differ between maternity units and influence TOLAC rates [28, 29]. The difference in TOLAC rates between the northern and southern parts of Belgium could be partly explained by this organizational factor which should be investigated in future studies of TOLAC provision.

Conclusion

Some organizational differences appear to affect the provision of TOLAC to women with a history of CS. Addressing these organizational factors, however, may not be sufficient to change practice, as the general tendency to perform a CS in the maternity unit is the main contributor to the percentage of TOLAC.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- c-section:

-

Cesarean section

- DDI:

-

Decision-to-delivery interval

- NICU:

-

Neonatal Intensive Care Unit

- OR:

-

Operating room

- TOLAC:

-

Trial of Labor After Cesarean

- VBAC:

-

Vaginal Birth after Cesarean

References

Betran AP, Ye J, Moller AB, Souza JP, Zhang J. Trends and projections of caesarean section rates: global and regional estimates. BMJ Glob Health. 2021;6(6):e005671.

European Perinatal Health report. Euro-Peristat; 2022.

Keag OE, Norman JE, Stock SJ. Long-term risks and benefits associated with cesarean delivery for mother, baby, and subsequent pregnancies: Systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS Med. 2018;15(1):e1002494.

Sandall J, Tribe RM, Avery L, Mola G, Visser GH, Homer CS, et al. Short-term and long-term effects of caesarean section on the health of women and children. Lancet. 2018;392(10155):1349–57.

Goemaes RFE, Laubach M, De Coen K, Roelens K, Bogaerts A. Perinatale gezondheid in Vlaanderen – Jaar 2021. Brussels: Studiecentrum voor Perinatale Epidemiologie; 2022.

Leroy Ch VLV. Santé périnatale en Wallonie – Année 2021. Brussels: Centre d’Épidémiologie Périnatale; 2022.

Van Leeuw VLC. Santé périnatale en Région bruxelloise – Année 2021. Brussels: Centre d’Épidémiologie Périnatale; 2022.

Antoine C, Young BK. Cesarean section one hundred years 1920–2020: the good, the bad and the ugly. J Perinat Med. 2020;49(1):5–16.

Visser GHA, Ayres-de-Campos D, Barnea ER, de Bernis L, Di Renzo GC, Vidarte MFE, et al. FIGO position paper: how to stop the caesarean section epidemic. Lancet. 2018;392(10155):1286–7.

Lydon-Rochelle M, Holt VL, Easterling TR, Martin DP. Risk of uterine rupture during labor among women with a prior cesarean delivery. N Engl J Med. 2001;345(1):3–8.

Sentilhes L, Vayssière C, Beucher G, Deneux-Tharaux C, Deruelle P, Diemunsch P, et al. Delivery for women with a previous cesarean: guidelines for clinical practice from the French College of Gynecologists and Obstetricians (CNGOF). Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2013;170(1):25–32.

Gynaecologists RCoOa. Birth After Previous Caesarean Birth. 2015.

ACOG Practice Bulletin No. 205: Vaginal Birth After Cesarean Delivery. Obstet Gynecol. 2019;133(2):e110–27.

(RANZCOG) WsHC. Birth after previous caesarean section. 2019.

Guidelines QC. Queensland Clinical Guideline: Vaginal birth after caesarean (VBAC) 2020; cited 2021 16/03/2021]. Available from: https://www.health.qld.gov.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0022/140836/g-vbac.pdf.

Vandenberghe G, Bloemenkamp K, Berlage S, Colmorn L, Deneux-Tharaux C, Gissler M, et al. The International network of obstetric survey systems study of uterine rupture: a descriptive multi-country population-based study. BJOG. 2019;126(3):370–81.

Harris PA, Taylor R, Minor BL, Elliott V, Fernandez M, O’Neal L, et al. The REDCap consortium: Building an international community of software platform partners. J Biomed Inform. 2019;95:103208.

Harris PA, Taylor R, Thielke R, Payne J, Gonzalez N, Conde JG. Research electronic data capture (REDCap)–a metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. J Biomed Inform. 2009;42(2):377–81.

National Institute for Health and Care Excellence: Clinical Guidelines. Caesarean birth. London: National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE)

Dy J, DeMeester S, Lipworth H, Barrett J. No. 382-Trial of Labour After Caesarean. Journal of obstetrics and gynaecology Canada. 2019;41(7):992–1011.

Tuffnell DJ, Wilkinson K, Beresford N. Interval between decision and delivery by caesarean section-are current standards achievable? Observational case series. Bmj. 2001;322(7298):1330–3.

Helmy WH, Jolaoso AS, Ifaturoti OO, Afify SA, Jones MH. The decision-to-delivery interval for emergency caesarean section: is 30 minutes a realistic target? BJOG. 2002;109(5):505–8.

Sayegh I, Dupuis O, Clement HJ, Rudigoz RC. Evaluating the decision–to–delivery interval in emergency caesarean sections. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2004;116(1):28–33.

Huissoud C, Dupont C, Canoui-Poitrine F, Touzet S, Dubernard G, Rudigoz RC. Decision-to-delivery interval for emergency caesareans in the Aurore perinatal network. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2010;149(2):159–64.

Yee LM, Liu LY, Grobman WA. Obstetrician call schedule and obstetric outcomes among women eligible for a trial of labor after cesarean. American journal of obstetrics and gynecology. 2017;216(1):75.e1-.e6.

Xu X, Lee HC, Lin H, Lundsberg LS, Campbell KH, Lipkind HS, et al. Hospital variation in utilization and success of trial of labor after a prior cesarean. American journal of obstetrics and gynecology. 2019;220(1):98.e1-.e14.

Chang JJ, Stamilio DM, Macones GA. Effect of hospital volume on maternal outcomes in women with prior cesarean delivery undergoing trial of labor. Am J Epidemiol. 2008;167(6):711–8.

White HK, le May A, Cluett ER. Evaluating a Midwife-Led Model of Antenatal Care for Women with a Previous Cesarean Section: A Retrospective. Comparative Cohort Stud Birth. 2016;43(3):200–8.

Keedle H, Peters L, Schmied V, Burns E, Keedle W, Dahlen HG. Women’s experiences of planning a vaginal birth after caesarean in different models of maternity care in Australia. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2020;20(1):381.

Acknowledgements

We are very grateful for the voluntary help of the B.OSS collaborators in each maternity, without whose support this research would not have been possible. Special thanks to the authors from the B.OSS collaborating group:

Ackermans, J. Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology St Elisabeth, Herentals, Belgium.

Anton, D. Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Cliniques du Sud Luxembourg – Saint-Joseph, Belgium.

Bafort, M. Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology AZ Alma, Eeklo, Belgium.

Batter, A. Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, IFAC Hôpital Princesse Paola, Belgium.

Belhomme, J. Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Centre Hospitalier Universitaire Saint-Pierre, Brussels, Belgium.

Beliard, A. Department of Gynaecology – Obstetrics Centre Hospitalier du Bois de l’Abbaye et de Hesbaye – site Seraing, Belgium.

Bollen, B. Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology ziekenhuis Noorderhart, Overpelt, Belgium.

Boon, V. Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Clinique Saint-Pierre, Belgium.

Bosteels, J. Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology Imelde Ziekenhuis, Bonheiden, Belgium.

Bracke, V. Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology St Lucas Ghent, Ghent, Belgium.

Ceysens, G. Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Centre Hospitalier Universitaire Ambroise Paré, Belgium.

Chaban, F. Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, GZA St Vincentius, Antwerp, Belgium.

Chantraine, F. Department of Gynaecology – Obstetrics CHR de la Citadelle, Liège, Belgium.

Christiaensen, E. Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology AZ St Jozef, Malle, Belgium.

Clabout, L. Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology AZ St Maarten, Mechelen, Belgium.

Cryns, P. Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology Klina, Brasschaat, Belgium.

Dallequin, M-C. Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology AZ Oudenaarde, Oudenaarde, Belgium.

De Keersmaecker, B. Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology AZ Groeninge, Kortrijk, Belgium.

De Keyser, j. Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Cliniques de l’Europe St Michel, Brussels, Belgium.

De Knijf, A. Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology AZ Delta Roeselare, Belgium.

Scheir, P. Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology AZ Glorieux Ronse, Belgium.

De Loose, J. Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology AZ Zeno, Knokke, Belgium.

De Vits, A. Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology AZ Jan Palfijn, Ghent, Belgium.

De Vos, T. Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology AZ St Eisabeth Zottegem, Zottegem, Belgium.

Debecker, B. Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, GZA St Augustinus, Antwerp, Belgium.

Delforge, C. Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Clinique et Maternité Sainte-Elisabeth, Namur, Belgium.

Deloor, J. Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology UZ Antwerpen, Antwerp, Belgium.

Depauw, V. Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology AZ St Jan campus Oostende, Oostende, Belgium.

Depierreux, A. Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Cliniques de l’Europe Ste Elisasbeth, Belgium.

Devolder, K. Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology St Andries, Tielt, Belgium.

Claes, L. Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology RZ Heilig Hart Tienen, Tienen, Belgium.

Dirx, S. Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology ziekenhuis Maas en Kempen, Maaseik, Belgium.

Eerdekens, C. Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology St Trudo ziekenhuis, St Truiden, Belgium.

Emonts, P. Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Centre Hospitalier Universitaire Notre-Dame des Bruyères, Belgium.

Goenen, E. Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Centre Hospitalier Régional du Val de Sambre, Belgium.

Grandjean, P. Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Centre Hospitalier Régional Mons Clinique Saint-Joseph, Mons, Belgium

Hollemaert, S. Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Centre Hospitalier Universitaire Tivoli, Brussels, Belgium.

Houben, S. Department of Gynaecology – Obstetrics Chirec Hôpital Delta, Brussels, Belgium.

Jankelevitch, E. Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology Jessaziekenhuis, Hasselt, Belgium.

Janssen, G. Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology St Franciscus, Heusden-Zolder, Belgium.

Quitnelier, J. Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology Jan Yperman, Ieper, Belgium.

Kacem, Y. Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Clinique Notre Dame de Grâce, Belgium.

Klay, C. Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Centre Hospitalier Régional de Namur, Namur, Belgium.

Laurent, A. Department of Gynaecology – Obstetrics CHC Montlégia, Liège, Belgium.

Legrève, J-F. Department of Gynaecology – Obstetrics Chirec Braine-l’Alleud-Waterloo, Belgium.

Lestrade, A. Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Hôpital de Jolimont, Belgium.

Lietaer, C. Department of Gynaecology – Obstetrics Clinique Sainte-Anne-Remi, Brussels, Belgium.

Loccufier, A. Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology St Jan Brugge, Belgium.

Logghe, H. Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, St Lucas, Brugge, Belgium.

Loumaye, F. Department of Gynaecology – Obstetrics Centre Hospitalier Peltzer – La Tourelle, Belgium.

Mariman, V. Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology AZ Nikolaas, St-Niklaas, Belgium.

Minten, N. Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology AZ Vesalius Tongeren, Tongeren, Belgium.

Mortier, D. Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology AZ Delta Menen, Belgium.

Mulders, K. Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology ASZ campus Aalst, Aalst, Belgium.

Palgen, G. Department of Gynaecology – Obstetrics Vivalia Hôpital Libramont, Belgium.

Pezin, T. Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Hôpitaux Iris Sud site Ixelles, Brussels, Belgium.

Polisiou, K. Department of Gynaecology – Obstetrics Centre Hospitalier Dinant, Belgium.

Riera, C. Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Hôpital Civil Marie Curie, Charleroi, Belgium.

Romain, M. Department of Gynaecology – Obstetrics Centre Hospitalier EpiCURA – Site Hornu, Belgium.

Rombaut, B. Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology AZ Damiaan, Oostende, Belgium.

Ruymbeke, M. Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, ZNA Jan Palfijn, Antwerp, Belgium.

Scharpé, K. Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology AZ St Blasius, Dendermonde, Belgium.

Schockaert, C. Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology OLV ziekenhuis campus Asse, Belgium.

Segers, A. Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology Dimpna ziekenhuis, Geel, Belgium.

Serkei, E. Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology St Rembertziekenhuis, Torhout, Belgium.

Steenhaut, P. Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Cliniques Universitaires Saint-Luc, Brussels, Belgium.

Steylemans, A. Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, ZNA Middelheim, Antwerp, Belgium

Thaler, B. Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology St Vincentius, Deinze, Belgium.

Van Dalen, W. Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology St Jozef Izegem, Izegem, Belgium.

Van De Poel, E. Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology AZ Monica, Deurne, Belgium.

Van Deynse, E. Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology AZ West Veurne, Veurne, Belgium.

Van Dijck, R. Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology Heilig Hart, Leuven, Belgium.

Van Holsbeke, C. Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology ZOL Genk, Genk, Belgium.

Van Hoorick, L. Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology AZ Rivierenland, Bornem, Belgium.

Van Olmen, G. Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology AZ Diest, Diest, Belgium.

Vanballaer, P. Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology Heilig Hartziekenhuis Mol, Belgium.

Vancalsteren, K. Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology UZ Gasthuisberg, Leuven, Belgium.

Vandeginste, S. Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology OLV ziekenhuis campus Aalst, Belgium.

Vandepitte, S. Department of Gynaecology – Obstetrics Centre Hospitalier de Mouscron, Belgium.

Verbeken, K. Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology AZ Lokeren, Lokeren, Belgium.

Vereecke, A. Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology Maria Middelares, Ghent, Belgium.

Verheecke, M. Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology AZ Turnhout, Turnhout, Belgium.

Watkins-Masters, L. Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Centre Hospitalier Régional Haute Senne – Le Tilleriau, Belgium

Wijckmans, V. Service of Obstetrics and perinatal Medicine, UZ Brussel, Brussels, Belgium.

Wuyts, K. Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology Heilig Hart ziekenhuis Lier, Lier, Belgium.

Funding

There was no funding for any part of this study, nor for writing the manuscript. The Belgian Obstetrical Surveillance System, B.OSS, is financially supported by the College of Mother and Newborn of the Federal Belgian Government.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Consortia

Contributions

GV, AV and CD conceptualized the study; GV, AV, NC, EVO, CL, RG contributed to the collection of data on organisational factors from the different hospitals; CL and RG provided data on TOLAC and VBAC rate from the different hospitals and merged the two datasets to an anonymised data set per region; MB merged the datasets from the different regions; MB, NC, EVO, analysed the data for the different regions; GV, AV and MB analysed the national data; MB provided statistical support and developed the figures; GV, AV, MB, ML and CD interpreted the data; GV, AV, MB, and CD wrote the first draft; all authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

GV, AV and CD conceptualized the study; GV, AV, NC, EVO, CL, RG contributed to the collection of data on organisational factors from the different hospitals; CL and RG provided data on TOLAC and VBAC rate from the different hospitals and merged the two datasets to an anonymised data set per region; MB merged the datasets from the different regions; MB, NC, EVO, analysed the data for the different regions; GV, AV and MB analysed the national data; MB provided statistical support and developed the figures; GV, AV, MB, ML and CD interpreted the data; GV, AV, MB, and CD wrote the first draft; all authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1:

Additional Table 1. Proportion of VBAC in case of TOLAC, according to location, size and organization of the maternity. Additional Table 2. Overall proportion of CS, according to location, size and organization of the maternity.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Vandenberghe, G., Vercoutere, A., Cuvellier, N. et al. Influence of organizational factors on the offer and success rate of a trial of labor after cesarean section in Belgium: an ecological study. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 23, 684 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12884-023-05984-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12884-023-05984-w