Abstract

The metastable ε-Fe2O3 is known to be the most intriguing ferrimagnetic and multiferroic iron oxide phase exhibiting a bunch of exciting physical properties both below and above room temperature. The present paper unveils the structural and magnetic peculiarities of a few nm thick interface layer discovered in these films by a number of techniques. The polarized neutron reflectometry data suggests that the interface layer resembles GaFeO3 in composition and density and is magnetically softer than the rest of the ε-Fe2O3 film. While the in-depth density variation is in agreement with the transmission electron microscopy measurements, the layer-resolved magnetization profiles are qualitatively consistent with the unusual wasp-waist magnetization curves observed by superconducting quantum interference device magnetometry. Interestingly a noticeable Ga diffusion into the ε-Fe2O3 films has been detected by secondary ion mass spectroscopy providing a clue to the mechanisms guiding the nucleation of exotic metastable epsilon ferrite phase on GaN at high growth temperature and influencing the interfacial properties of the studied films.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The combination of magnetic and semiconductor materials within a single heterostructure provides vast opportunities for designing novel functional spintronic devices1,2,3. Among the known magnetic materials, iron oxides, though having a simple formula, exhibit rich variety of magnetic properties depending on the iron oxidation state and coordination. Metastable ε-Fe2O3, an exotic member of the iron oxides family, is the most intriguing phase not existing in the bulk and having been so far only crystallized in the form of nanoparticles4,5,6 and thin epitaxial films on a number of oxide substrates7,8,9. The ε-Fe2O3 phase is ferrimagnetic with largest magnetocrystalline anisotropy among the iron oxides responsible for coercivity values exceeding 2 T in the nanocrystalline form4,10,11 and 1 T in epitaxial layers7. Further, ε-Fe2O3 exhibits pyroelectric properties, room-temperature magnetoelectric coupling12,13 and non-linear magneto-optical effects11,13,14. Extending the successful attempts to stabilize epsilon ferrite on a number of oxide substrates, quite recently single crystalline layers of this material have been stabilized on GaN(0001) semiconductor surface by laser-assisted molecular beam epitaxy. The feasibility to grow the exotic ε-Fe2O3 phase along with three other iron oxide phases (Fe3O4, α-Fe2O3 and γ-Fe2O3) has been demonstrated15. The choice of the semiconducting material in this study is supported mainly by the wide usability of the gallium nitride in the modern optoelectronic and microelectronic devices such as bright LEDs, HEMT transistors for high-power, high-frequency, high-temperature and high radiation resistant applications16,17. Incorporating ε-Fe2O3 layer with controllable magnetization/polarization into a GaN-based device is supposed to provide additional functionality and therefore opens the way for the novel optoelectronic, electronic and spintronic applications18,19.

Comparing the results of the previously reported works on ε-Fe2O3 epitaxial films7,8,9,12,20 one can conclude that magnetic properties of the ε-Fe2O3 layer dramatically depend on the composition of the neighboring buffer layer and the chosen substrate. Interestingly, a peculiar double-hysteresis wasp-waist loop indicating the presence of an additional magnetically soft component was observed in ε-phase layers grown on SrTiO 3 (111) (STO)7,21, AlFeO3 (AFO)/Nb:STO12, GaFeO3 (GFO)/Al2O3(0001)8, yttrium stabilized zirconia (YSZ)9 and GaN15 substrates and still has not clearly been understood. In contrast to this, ordinary rectangular or oval-shaped loops were demonstrated for ε-Fe2O3 thin films grown onto GaFeO3/STO(111) and GaFeO3/Al2O3(0001)8,22. Moreover, in the latter work Thai et al. reported that ε-Fe2O3 films got saturated in field of B = 0.5 T8, despite the saturation field of ε-phase being typically in the range of 2–3 T4,10. For ε-Fe2O3 nanoparticles, the step-like shape of the loop was attributed to the co-existence of a major ε-phase with a minor γ-Fe2O3 fraction5,23. Quite similarly, Corbellini et al. reported a ≈ 10 % fraction of magnetite (Fe3O4) in the PLD-grown Al-doped ε-Fe2O3 films resulting in non-zero magnetic moment at temperatures higher than 500 K20.

While the majority of the cited works report the need to grow a stand alone buffer layer of a Pna21 space group material (GFO or AFO) prior to the ε-Fe2O3 film deposition, the ferrite-on-GaN technology is claimed not to require any buffer. In this paper, we show that a few nanometer-thick Ga rich transition layer with properties different from the main ε-Fe2O3 film is formed at the interface upon high temperature deposition. The transition layer is supposed to define the Pna21 lattice structure of the further growing iron oxide layer thus leading to the nucleation of the exotic ε-Fe2O3 phase. In the present work we report the structural, chemical and magnetic peculiarities of the interface layer studied by a number of complementary methods that allow a separate evaluation of the structural and magnetic properties related to the bulk and interface film regions. In contrast to our previous report15 which focused either on the near surface region (reflection high-energy electron diffraction, atomic force microscopy, X-ray absorbtion spectroscopy) or on the bulk-integrated properties (X-ray diffraction, vibrating sample magnetometry), the present paper involves a depth resolved analysis of the ε-Fe2O3/GaN films performed by polarized neutron reflectometry (PNR), transmission electron microscopy (TEM) and secondary ion mass spectroscopy (SIMS).

Experimental

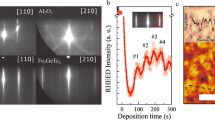

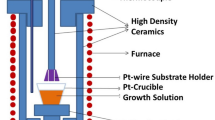

The three micrometer-thick Ga terminated GaN (0001) layer acting as the host surface for the iron oxide deposition was fabricated by means of MOVPE on the commercial Al2O3 (0001) substrates. Epsilon ferrite films of 40–60 nm thickness were grown by means of laser molecular beam epitaxy from a stoichiometric Fe2O3 target ablated by pulsed KrF excimer laser radiation. The iron oxide deposition was performed in oxygen atmosphere at a pressure of 0.2 mbar using the growth conditions similar to those reported in our previous publication15. Despite using a lower growth temperature of 700 °C (800 °C in our previous report) we could confirm the epitaxial stabilization of ε-Fe2O3 phase by in-situ reflection high-energy electron diffraction (RHEED) reciprocal space mapping and ex-situ X-ray diffraction (XRD) methods. As was reported earlier the ε-Fe2O3 layer grows with the polar [001] axis oriented perpendicular to the substrate surface and the ε-Fe2O3 [100] easy magnetization axis parallel to one of the three equivalent GaN1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10 directions resulting in three crystallographic domains at 120° to each other.

As confirmed by atomic force microscopy, ε-Fe2O3 forms a uniform layer on the GaN step-and-terrace surface (Fig. 1a,b). On the nanometer scale the epsilon ferrite film surface shows mounds 25–35 nm in width and up to 10 nm in height. A more detailed investigation of the ε-Fe2O3/GaN morphology was carried out on a Jeol JEM-2100F transmission electron microscope (acceleration voltage 200 kV, point-to-point resolution 0.19 nm) operated in conventional bright-field and high-resolution imaging modes. TEM images presented in Fig. 1c,d confirm that the ε-Fe2O3 film is continuous with internal structure consisting of columns with the lateral size of 30–50 nm. The film surface roughness is a few nanometers peak-to-valley and caused by slightly different height of the neighboring columns. A similar structure with somewhat larger surface roughness was reported by other authors for ε-Fe2O3 layers grown on GaFeO3/STO, GaFeO3/YSZ surfaces7,8,9,12. The most likely reason for the columnar growth is the lower symmetry of the orthorhombic ε-Fe2O3 as compared to hexagonal GaN. At the early growth stage, individual islands have a threefold rotational degree of freedom in nucleation, leading to an in-plain rotation of 120° between grains. Apparently these defects persist throughout the island coalescence stage which results in the growth of vertical columns with antiphase boundaries in between them. The substrate interface of the epsilon ferrite film is much smoother than the surface. Interestingly, the high-resolution TEM suggests that a 4–5 nm thick interface layer with degraded crystalline quality is formed between GaN and ε-Fe2O3. This layer appears lighter in the TEM images which might indicate that this layer has a lower density. While the high resolution TEM image in Fig. 1 shows distinctly the atomic layers corresponding to c = 9.47 Å in ε-Fe2O3 and c = 5.189 Å in GaN, it is quite difficult to recognize a regular atomic structure in the transition layer at the interface. As was mentioned in our previous publication15 the RHEED patterns observed during growth of the first few nanometers are characteristic of a slightly disordered lattice with the lateral periodicity being reduced compared to that of ε-Fe2O3.

Magnetization measurements with magnetic field of up to 3 T applied in plane of the film were carried out using a Quantum Design 5XL magnetic property measurement system (MPMS) superconducting quantum interference device (SQUID) magnetometer in the temperature range from 10 to 380 K. Hysteresis loops measured in a 60 nm ε-Fe2O3 film at different temperatures are shown in Fig. 2a. Magnetic field was applied in the sample plane parallel to one of the [100] easy axis. For each temperature the loops were corrected for linear diamagnetic contribution of GaN/Al2O3 substrate. Saturation magnetization of about 80 emu/cm3 at T = 10 K is somewhat lower than the values reported for ε-Fe2O3 thin films and nanoparticles4,12. It is also lower than the values reported in our previous publication15 where ε-Fe2O3 layers were grown at a higher temperature of 800 °C. The coercive field B c gradually increased as the temperature decreased from 180 mT at 380 K to 580 mT at 5 K.

The wasp-waist magnetization loop shown in Fig. 2a can be qualitatively decomposed to hard and soft component loops by subtracting 2M soft /π⋅arctan(B/B soft ) function with temperature-independent M soft = 25 emu/cm3 and B soft = 76 mT, chosen to eliminate the magnetization jump at zero field (Fig. 2b). In this way the coercivity of the hard component can be estimated as 500 mT at RT and 800 mT at 10 K. These values are much closer to the characteristic ε-Fe2O3 coercivity but still lower than the 2 T values reported for ε-Fe2O3 nanoparticles4,10. Another reason for decreased coercivity is that when the applied field is parallel to the easy axis of one crystallographic domain, it makes 60° with the easy axes of the other two, making them switch magnetization in distinctly lower fields due to the presence of the off-easy-axis magnetic field component24. As it was noted by Ohkoshi et al.13, the coercivity dramatically depends on the nanoparticle size. Assuming that the ε-Fe2O3/GaN films consist of single domain columnar grains the B c of 500 mT would correspond to the column size of 9–10 nm–much smaller than the size observed by TEM. It must be noted that the columns visible in the cross-section TEM images may have internal structure consisting of even smaller crystallographic domains. A more detailed investigation involving planar TEM studies is required to clarify the origin of the decreased coercivity.

Taking into account the fact that in thin films a phase separation often occurs at the interface25,26,27 we have conducted PNR measurements of the ε-Fe2O3/GaN heterostructures aimed at layer-resolved study of magnetization distribution inside the epsilon ferrite layer. The important technical aspects of our PNR experiment are described below, while the details of methodology can be found elsewhere28,29. Neutron reflectometry experiments were performed at the instruments D1730 (ILL, Grenoble, France) and BL17 SHARAKU31 (J-PARC MLF, Tokai, Japan) in polarized time-of-flight mode. The beamtime for room- and low-temperature PNR measurements was distributed between D1732 and SHARAKU instruments, respectively. Sample temperature and magnetic field at D17 instrument were controlled by 7 T vertical field cryomagnet with single-crystalline sapphire windows. Neutrons with wavelengths 4 < λ < 16 Å were used in the time-of-flight mode to maximize the incoming flux and keep the constant polarization efficiency in the whole q-range. Polarization of the direct beam P0 = 99% was measured by an analyzer. The minimum guide field required to prevent beam depolarization was B g = 50 mT, likely due to a residual remanent field in the high-field superconducting magnet coils. The experiment was performed without polarization analysis. R+ and R− reflectivities were acquired without distinction of the spin-flip and non spin-flip components. Intensity of the reflected beam was detected by two-dimensional 3He position-sensitive detector (PSD) and corrected for polarization efficiency, reflected beam divergence and wavelength resolution33,34. At SHARAKU the magnetic field was applied parallel to the incident neutron beam and spin polarization by horizontal-field 4 T cryomagnet. Neutron beam with the wavelengths 2 Å < λ < 8 Å was provided with constant polarization efficiency of P0 = 98.5%. R+ and R− reflectivities were detected by a 3He gas tube PSD.

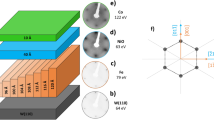

PNR curves R(Q z ) measured at temperatures T = 300 K and T = 10 K shown in Fig. 3a are multiplied by \({Q}_{z}^{4}\) to compensate the Fresnel decay and provide better visibility to all the features of the reflectivity function. Note, that all the curves are shifted along vertical axis for clarity reasons: the multiplication factor is indicated for each curve. The splitting of R+(Q z ) and R−(Q z ) is proportional to the net magnetization of the film along the field direction. Because of the relatively small magnetic moment of the ε-Fe2O3 film, the splitting is hardly distinguishable at T = 300 K, but clearly observed after the sample was cooled to T = 10 K in magnetic field of B = 2 T. A set of PNR measurements was performed on the field-decreasing hysteresis loop branch from +62 T to +50 mT where both hard and soft magnetic components are magnetized positive (Fig. 1 in Supplemental Information). After that a negative field of B = −2 T has been applied to achieve negative saturation and another measurement was carried out at B = +100 mT. This point on the field-increasing loop branch (Fig. 2) corresponds to the state in which the soft magnetic component has already switched to the positive saturation while the hard magnetic component is still in negative remanence.

PNR curves measured at (a) T = 300 K (B = 50 and 2000 mT) and at T = 10 K (B = 2000 mT). Symbols represents the experimental data while the solid lines are calculated. The curves are shifted vertically for clarity. (b) Nuclear SLD profiles delivered by fitting routine. (c) Magnetic SLD profiles obtained at T = 10 K and different magnetic fields. Dashed line is corresponding to the ρ n in the arbitrary units. (d) Layer-specific and total area-normalized magnetization curves for ε-Fe2O3 film at T = 10 K.

Discussion

For quantitative discussions of the structure and magnetic properties of the studied sample the PNR data were fitted using the Parratt algorithm in GenX software package35. For neutron reflectometry the buffer GaN layer with thickness of 3 μm is considered as the bulk medium. Thus reflectivity data was fitted assuming the model consisted of GaN substrate, transition layer (interface) and ε-Fe2O3 layer. These parameters are summarized in the nuclear scattering length density (SLD) and magnetic SLD profiles (ρ n (z) and ρ m (z), respectively) shown in Fig. 3b and c. The solid line in Fig. 3b corresponds to the nuclear SLD profile \({\rho }_{n}(z)=\frac{{\sum }_{i\mathrm{=1}}^{N}{b}_{i}}{{V}_{m}}=\frac{\rho {N}_{a}{\sum }_{i\mathrm{=1}}^{N}{b}_{i}}{{\sum }_{i\mathrm{=1}}^{N}{M}_{i}}\) where b i is scattering length of i-th of N atoms within the unit cell of volume V m , ρ is a density of the material, M i is the molecular weight, N a is the Avogadro constant. The initial guess contained the literature values of scattering lengths and densities and nominal thickness of iron oxide layer; then the densities and thicknesses of ε-Fe2O3 and interface layer were allowed to vary freely in the fitting routine. All PNR datasets were fitted simultaneously with the same structural parameters and varying magnetizations of the main and interface layers corresponding to different temperature and field conditions and resolution functions corresponding to the D17 and SHARAKU instruments. The minimum found by the fitting algorithm (goodness of the fit χ2 = 1.42) corresponds to the model containing interface layer with thickness of d i = 37 ± 3 Å and roughness σ i = 24 ± 10 Å between iron oxide and GaN buffer. The obtained density of ε-Fe2O3 layer is reduced by 5% and GaN density is reduced by 1.5% compared to the literature values (dashed lines in Fig. 3b). The deviations from expected bulk values are typical for thin film growth and associated strain, while the larger 5% deviation may be explained by the columnar growth and therefore higher density of defects in the ε-Fe2O3 layer. The nuclear SLD of the interface layer is reduced compared to the main film of ε-Fe2O3 and close to the nominal value of ρ n of GaFeO3 (blue dashed line in Fig. 3b).

Magnetic SLD ρ m is directly proportional to the magnetization component M parallel to B: ρ m = 2.853⋅10−9⋅M Å−2, where M is given in emu/cm3 units36. Therefore, SLD profile ρ m (z) represents in-depth distribution of the magnetization of the film. Assuming a homogeneous distribution of magnetization in the sample plane, the magnetization contributions from the main ε-Fe2O3 m m (B) and interfacial layers m i (B) were correlated through the area-normalized total magnetic moments m t measured by SQUID: m t ⋅(d m + d i ) = m m ⋅d m + m i ⋅d int , where d m and d i are thicknesses of the main ε-Fe2O3 and interface layers, respectively.

The results of the fitting of magnetic PNR data obtained at 10 K are shown in Fig. 3c,d. The dashed line in Fig. 3c corresponds to the scaled nuclear SLD profile of Fig. 3b for convenience. The solid lines represent the magnetic SLD profiles ρ m (z) of at B = 2000 mT, 500 mT, 50 mT on the field-decreasing and 100 mT on the field-increasing hysteresis loop branches. The layer-resolved magnetization values measured at T = 10 K as a function of magnetic field are summarized in Fig. 3d. Interestingly, the interface layer appears to be magnetically much softer compared to the main ε-Fe2O3 layer. As an illustration, the interface layer remains saturated until relatively small field of 50 mT on the field-decreasing hysteresis loop branch (Fig. 3c) while the magnetization of the main layer is already reduced by half at this point. On the field-increasing branch recorded after applying a negative 2 T field, the main ε-Fe2O3 layer is still in negative remanence at B = 100 mT while the interface layer has already switched to positive saturation. This behavior resembles the loops shown in Fig. 2 that demonstrate a pronounced two-step magnetization switching: a wide hysteretic magnetization rotation between −2 T and 2 T, representing the averaged switching of 3 columnar domains, and a narrow zero-remanence magnetization switching with saturation of ≈0.25M s . However, the contribution of the interface layer to the total magnetization is only 0.08 M s as found from our PNR data. This suggests that another soft magnetic phase is likely present in the sample though cannot be distinguished in the PNR experiment. The most plausible candidates for the soft-magnetic phase are minor γ− Fe2O3 and Fe3O4 fractions homogeneously distributed within the sample plane5,20,23 although not pronounced in X-ray diffraction and X-ray spectroscopy data15. In this case further attempts of mapping of the hidden soft-magnetic component in real-space can be performed by means of soft X-ray photoemission electron microscopy. One must also take into account that the columnar structure of the ε-Fe2O3 films observed by TEM suggests that antiphase boundaries are present in considerable concentration between the columns especially in the interface region. As was pointed out in ref.37. the antiphase boundaries in iron oxides may account for the soft magnetic behavior. PNR is a laterally averaging technique and only sensitive to long-range ordered moments. Therefore, magnetic moments located in minor phase fractions of small volume, or at the columnar antiphase boundaries cannot be distinguished by this method.

The reduced crystalline order observed by TEM (this work) and RHEED (ref.15.) within a few nanometer thick layer at the film - substrate interface is in general agreement with the reduced density. Soft magnetism of the interface region is confirmed by the presented PNR data. The reduced order at the interface however gives no clue as to why the exotic metastable ε-Fe2O3 iron oxide phase nucleates on GaN and moreover grows in the form of epitaxial crystallographically well oriented layers.

A probable explanation can be related to the interfacial gallium sourced in small quantities into the iron oxide film by the GaN substrate heated to 700−800 °C during the growth stage. It is well known that GaN becomes unstable at 900–1000 °C. For example, after 1 hour annealing at T = 900 °C in H2, thermal degradation of GaN is observed accompanied by formation of individual Ga droplets on the surface38. At more moderate conditions an enhanced Ga diffusion is known to occur. Annealing at 900 °C was found to enhance Ga diffusion in Fe3O4 and Fe3O4/Ga2O3 films grown on GaN templates by metal organic chemical vapor deposition (MOCVD), resulting in noticeable mixing at the iron oxide/GaN interface39,40.

To investigate the chemical composition of ε-Fe2O3/GaN films, SIMS depth profiling was carried out. Sputtering was performed by 1 kV Ar ions (ion current 10 nA) in a 200 μm crater at the rate of 15 s/nm. The mass-spectra of positive secondary ions were collected from a 150 μm area using 25 kV Bi ions. Figure 4 shows the profiles of Fe, O, Ga and N single ions and Ga-Ga pair-ion. One has to take into account that SIMS profiles actually show a convolution of the concentration depth profile with the surface and interface roughness caused by inhomogeneity of the film thickness. This makes it difficult to accurately determine the exact depth corresponding to the Fe2O3/GaN interface. However using the surface roughness (about 5–7 nm) and the interface roughness (below 2 nm) from AFM, TEM and PNR studies one can readily distinguish two different intensity variation regions in the SIMS profiles. (i) A sharp intensity variation with the width of 5–7 nm present in the profiles of all the monitored elements within the depth region of 230–300 Å is marked with a gray rectangle. We suggest that this variation is due to the surface roughness. (ii) A much slower variation present in the profiles of Ga, Fe and O extending beyond the gray rectangle (depth region of 100–230 Å). It is reasonable to conclude that this variation reflects the actual concentration change. As the Ga concentration is decreasing and Fe is increasing towards the surface, we conclude that the region near the interface is Ga-rich and Fe-deficient. We would like to stress out that the interface region should not be confused with the region marked by the gray rectangle in Fig. 4 as the latter just gives the idea of SIMS profile broadening due to inhomogeneity of the film thickness. Extension of the Ga profile far from the interface into the film region where the profile of N is close to zero suggests diffusion (or any other kind of atomic penetration e.g. floating) of Ga atoms into the film during growth. The effect of Ga atomic penetration is further supported by the Ga-Ga pair-ion profile shown in Fig. 4b. Since the probability of pair-ion formation is proportional to the square of single-ion concentration, one can distinguish concentration variation (pair ion shows twice steeper slope) from inhomogeneity (pair-ion shows the same slope) by comparing single/pair-ion profiles in log scale. Indeed, as can be seen from Fig. 4b the Ga-Ga intensity decay is faster than that of Ga, supporting the idea of atomic penetration. Noteworthy, the Fe intensity is increasing towards the surface almost synchronously with the Ga intensity drop keeping the total intensity of Fe + Ga almost constant across the film. This suggests that gallium substitutes iron in the interface region of the iron oxide layer leading to formation of Ga x Fe(1−x)O3 compound isostructural to to ε-Fe2O341. Thus one can claim that the interfacial region is Ga rich and Fe deficient as opposed to the top part of the iron oxide film. Formation of gallium ferrite is a probable scenario, which can explain both the magnetic degradation of the Fe2O3/GaN interface region and the magnetization loop shapes similar to those reported for ε-Fe2O3 layers grown on GaFeO3 buffer by Thai et al.8.

The gallium-assisted scenario of ε-Fe2O3 growth on GaN is the natural assumption at least in view of works where the epsilon-ferrite epitaxial layers were grown on top of a GaFeO3 or AlFeO3 buffers serving to seed the Pna21 crystal structure. In addition, ε-ferrite can also be produced in the form of randomly oriented nanocrystals or nanowires by sol-gel technique without any isostructural seeding. Moreover, in a number of works ε-Fe2O3 epitaxial layers were grown without an isostructural buffer7,9,21. Importantly, the common feature of all the works on ε-Fe2O3Fe2O3, to our knowledge, is the nanostructural form of epsilon ferrite–even in epitaxial layers nano-sized columns are observed by means of TEM. Thus one can assume that an important prerequisite for the metastable ε-Fe2O3 phase nucleation is formation of the nanoscale objects. In such objects with high surface-to-volume ratio the energy considerations can favor the formation of a metastable phase otherwise not existing in the bulk form. One of the driving forces that induce granular epitaxial growth is the higher symmetry and smaller lattice constant of the substrate as compared to the iron oxide layer. In this case the grains at the first stage of growth nucleate incoherently upon coalescence thus facilitating columnar growth. Unfortunately, we cannot unambiguously distinguish whether gallium plays the primary role in formation of Pna21 GaFeO3 and just facilitation of the granular growth of iron oxide on GaN without dedicated experiments. This issue can be further investigated by blocking Ga diffusion through introduction of a barrier layer, such as MgO or Al2O3 between GaN and ε-Fe2O3. In support of importance of the columnar structure our extended studies of Fe2O3Fe2O3 growth on GaN presented in ref.15. show that at lower growth temperature (below 800° C) and at lower oxygen pressure (below 0.2 mbar) a more stable α-Fe2O3 phase grows on GaN instead of ε-Fe2O3 as evidenced by in situ electron and ex situ X-ray diffraction studies. Importantly the α-Fe2O3 layers are considerably more uniform than the ε-Fe2O3 layers. Since the α-phase is antiferromagnetic (or weak ferrimagnetic above the Morin temperature), the magnetic properties of the films containing α-Fe2O3 are much deteriorated compared to ε-Fe2O3 films in terms of saturation magnetization and coercive field.

Conclusion

In the present work a complementary structural, chemical and magnetic in-depth investigation of the ε-Fe2O3 epitaxial thin films grown on GaN (0001) surface by pulsed laser deposition is reported. In agreement with the other works describing the growth of epsilon ferrite films on oxide substrates, the ε-Fe2O3/GaN films were shown to have columnar structure naturally assigned to the presence of the 120° crystallographic domains. Most importantly, a few-nm thick transition layer with distinctly different properties has been detected at the interface between ε-Fe2O3 and GaN. The depth-resolved magnetization profiles obtained by PNR have shown that this interface layer has a lower nuclear SLD and is magnetically softer than the main volume of the ε-Fe2O3 film. While the density variation is in agreement with the transmission electron microscopy measurements, the soft magnetic behavior is shown to be related to the two component magnetization loops observed in the same samples by SQUID magnetometry. Interestingly the SIMS has shown that the interface region is Ga rich and Fe deficient. We conclude that the main ε-Fe2O3 film is likely to inherit the orthorhombic Pna21 structure from the isostructural GaFeO3-like interface layer, that forms at the early iron oxide deposition stage due to thermal migration of Ga atoms from the substrate. The reported observations shed light onto the mechanisms guiding nucleation of the exotic metastable epsilon ferrite phase on GaN and influencing the structural and magnetic properties of the studied films.

References

Prinz, G. A. Hybrid ferromagnetic-semiconductor structures. Science 250, 1092–1098 (1990).

Ohno, Y. et al. Electrical spin injection in a ferromagnetic semiconductor heterostructure. Nature 402, 790–792 (1999).

Wolf, S. et al. Spintronics: a spin-based electronics vision for the future. Science 294, 1488–1495 (2001).

Jin, J., Ohkoshi, S.-I. & Hashimoto, K. Giant coercive field of nanometer-sized iron oxide. Advanced Materials 16, 48–51 (2004).

Jin, J., Hashimoto, K. & Ohkoshi, S.-I. Formation of spherical and rod-shaped ε-Fe2O3 nanocrystals with a large coercive field. Journal of Materials Chemistry 15, 1067–1071 (2005).

Sakurai, S., Namai, A., Hashimoto, K. & Ohkoshi, S.-i First observation of phase transformation of all four Fe2O3 phases (γ-ε-β-α-phase). Journal of the American Chemical Society 131, 18299–18303 (2009).

Gich, M. et al. Epitaxial stabilization of ε-Fe2O3 (00l) thin films on SrTiO3 (111). Applied Physics Letters 96, 112508 (2010).

Thai, T. M. N. et al. Stabilization of metastable ε-Fe2O3 thin films using a GaFeO3 buffer. Journal of Applied Physics 120, 185304 (2016).

Corbellini, L. et al. Epitaxially stabilized thin films of ε-Fe2O3 (001) grown on YSZ (100). Scientific Reports 7 (2017).

Gich, M. et al. Large coercivity and low-temperature magnetic reorientation in ε-Fe2O3 nanoparticles. Journal of Applied Physics 98, 044307 (2005).

Namai, A. et al. Hard magnetic ferrite with a gigantic coercivity and high frequency millimetre wave rotation. Nature communications 3, 1035 (2012).

Gich, M. et al. Multiferroic iron oxide thin films at room temperature. Advanced Materials 26, 4645–4652 (2014).

Ohkoshi, S.-I. et al. Nanometer-size hard magnetic ferrite exhibiting high optical-transparency and nonlinear optical-magnetoelectric effect. Scientific Reports 5, 14414 (2015).

Ohkoshi, S.-i et al. Mesoscopic bar magnet based on ε-Fe2O3 hard ferrite. Scientific reports 6, 27212 (2016).

Suturin, S. et al. Tunable polymorphism of epitaxial iron oxides in the four-in-one ferroic-on-gan system with magnetically ordered α-, γ-, ε-ε-Fe2O3 and Fe2O4 layers. arXiv 1712.05632 [cond-mat.mtrl-sci] (2017).

Pearton, S. J. & Kuo, C. GaN and related materials for device applications. MRS Bulletin 22, 17–21 (1997).

Pearton, S. J. GaN and related materials II, vol. 7 (CRC Press, 2000).

Scott, J. Data storage: Multiferroic memories. Nature Materials 6, 256–257 (2007).

Gajek, M. et al. Tunnel junctions with multiferroic barriers. Nature Materials 6, 296 (2007).

Corbellini, L., Lacroix, C., Ménard, D. & Pignolet, A. The effect of Al substitution on the structural and magnetic properties of epitaxial thin films of epsilon ferrite. Scripta Materialia 140, 63–66 (2017).

Hamasaki, Y. et al. Crystal structure and magnetism in κ-Al2O3-type Al x Fe2−xO3 films on SrTiO3 (111). Journal of Applied Physics 122, 015301 (2017).

Katayama, T., Yasui, S., Hamasaki, Y., Osakabe, T. & Itoh, M. Chemical tuning of room-temperature ferrimagnetism and ferroelectricity in ε-Fe2O3-type multiferroic oxide thin films. Journal of Materials Chemistry C 5, 12597–12601 (2017).

López-Sánchez, J. et al. Growth, structure and magnetism of ε-Fe2O3 in nanoparticle form. RSC Advances 6, 46380–46387 (2016).

Stoner, E. C. & Wohlfarth, E. A mechanism of magnetic hysteresis in heterogeneous alloys. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London A: Mathematical, Physical and Engineering Sciences 240, 599–642 (1948).

Bibes, M. et al. Nanoscale multiphase separation at La2/3Ca1/3MnO3/SrTiO3 interfaces. Physical Review Letters 87, 067210 (2001).

Seo, J. W. et al. Interface formation and defect structures in epitaxial La2Zr2O7 thin films on (111) Si. Applied Physics Letters 83, 5211–5213 (2003).

Ukleev, V. et al. Magnetic properties of the SiO2(Co)/GaAs interface: Polarized neutron reflectometry and squid magnetometry. Physical Review B 86, 134424 (2012).

Ankner, J. & Felcher, G. Polarized-neutron reflectometry. Journal of Magnetism and Magnetic Materials 200, 741–754 (1999).

Zabel, H., Theis-Brohl, K., Wolff, M. & Toperverg, B. Polarized neutron reflectometry for the analysis of nanomagnetic systems. IEEE Transactions on Magnetics 44, 1928–1934 (2008).

Saerbeck, T. et al. Recent upgrades of the neutron reflectometer D17 at ILL. J. Appl. Crystallogr. 51 (2018).

Yamada, N. L., Takeda, M. & Yamazaki, D. Neutron reflectometers in J-PARC. Hamon 24, 288–295 (2014).

Ukleev, V., Chumakov, A., Saerbeck, T. & Vorobiev, A. Neutron reflectometry of exotic ε-Fe2O3 thin films. Institut Laue-Langevin (ILL), https://doi.org/10.5291/ILL-DATA.5-54-226 (2017).

Wildes, A. Scientific reviews: Neutron polarization analysis corrections made easy. Neutron News 17, 17–25 (2006).

Cubitt, R., Saerbeck, T., Campbell, R. A., Barker, R. & Gutfreund, P. An improved algorithm for reducing reflectometry data involving divergent beams or non-flat samples. Journal of Applied Crystallography 48 (2015).

Björck, M. & Andersson, G. Genx: an extensible X-ray reflectivity refinement program utilizing differential evolution. Journal of Applied Crystallography 40, 1174–1178 (2007).

Zhu, Y. Modern techniques for characterizing magnetic materials (Springer Science & Business Media, 2005).

Sofin, R. G. S., Wu, H.-C. & Shvets, I. V. Anomalous magnetization reversal due to proximity effect of antiphase boundaries. Physical Review B 84, 212403 (2011).

Sun, C. et al. Thermal stability of GaN thin films grown on (0001) Al2O3, (01\(\bar{1}\)2) Al2O3 and (0001)Si 6H-SiC substrates. Journal of Applied Physics 76, 236–241 (1994).

Huang, S. et al. Influence of oxygen precursors and annealing on Fe3O4 films grown on GaN templates by metal organic chemical vapor deposition. Journal of Vacuum Science & Technology B, Nanotechnology and Microelectronics: Materials, Processing, Measurement, and Phenomena 32, 052801 (2014).

Xu, Z. et al. The compositional, structural, and magnetic properties of a Fe3O4/Ga2O3/GaN spin injecting hetero-structure grown by metal-organic chemical vapor deposition. Applied Surface Science 388, 141–147 (2016).

Abrahams, S., Reddy, J. & Bernstein, J. Crystal structure of piezoelectric ferromagnetic gallium iron oxide. The Journal of Chemical Physics 42, 3957–3968 (1965).

Acknowledgements

We thank V. Kocsis and N.D. Khanh for technical assistance, K. Kakurai for useful discussions and ILL and J-PARC facilities for provided neutron beamtime. The authors wish to acknowledge V. V. Lundin for providing GaN/Al2O3 wafers. This work has been supported by RSF (project no. 17-12-01508) in part related to development of epsilon ferrite growth technology and by RFBR (project no. 18-02-00789) in part related to film characterization. TEM studies have been performed on the equipment of “Material science and characterization in advanced technology” Federal Joint Research Center supported by the Ministry of Education and Science of the Russian Federation (id RFMEFI62117X0018).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

V.U. and S.S. conceived the experiment, V.U., S.S., T.N., T.S., T.H., A.S., D.K. and N.Y. conducted the experiments, T.A. and N.S. jointly conceived the project. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing Interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Ukleev, V., Suturin, S., Nakajima, T. et al. Unveiling structural, chemical and magnetic interfacial peculiarities in ε-Fe2O3/GaN (0001) epitaxial films. Sci Rep 8, 8741 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-018-25849-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-018-25849-z

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.