Abstract

Plasma phosphorylated-tau181 (p-tau181) showed the potential for Alzheimer’s diagnosis and prognosis, but its role in detecting cerebral pathologies is unclear. We aimed to evaluate whether it could serve as a marker for Alzheimer’s pathology in the brain. A total of 1189 participants with plasma p-tau181 and PET data of amyloid, tau or FDG PET were included from ADNI. Cross-sectional relationships of plasma p-tau181 with PET biomarkers were tested. Longitudinally, we further investigated whether different p-tau181 levels at baseline predicted different progression of Alzheimer’s pathological changes in the brain. We found plasma p-tau181 significantly correlated with brain amyloid (Spearman ρ = 0.45, P < 0.0001), tau (0.25, P = 0.0003), and FDG PET uptakes (−0.37, P < 0.0001), and increased along the Alzheimer’s continuum. Individually, plasma p-tau181 could detect abnormal amyloid, tau pathologies and hypometabolism in the brain, similar with or even better than clinical indicators. The diagnostic accuracy of plasma p-tau181 elevated significantly when combined with clinical information (AUC = 0.814 for amyloid PET, 0.773 for tau PET, and 0.708 for FDG PET). Relationships of plasma p-tau181 with brain pathologies were partly or entirely mediated by the corresponding CSF biomarkers. Besides, individuals with abnormal plasma p-tau181 level (>18.85 pg/ml) at baseline had a higher risk of pathological progression in brain amyloid (HR: 2.32, 95%CI 1.32–4.08) and FDG PET (3.21, 95%CI 2.06–5.01) status. Plasma p-tau181 may be a sensitive screening test for detecting brain pathologies, and serve as a predictive biomarker for Alzheimer’s pathophysiology.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Amyloid accumulation, tau deposits and neurodegeneration are the most representative pathological features of Alzheimer’s disease (AD). Detection of these pathologies are vital for screening out the target population at risk among people with intact cognition or mild cognitive impairment (MCI). Positron emission tomography (PET) and cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) are considered to be the most effective methods for detecting and tracking pathological changes in the brain. However, PET neuroimaging as a sensitive technique is hard to be added into the clinical practice due to its huge cost and radioactive burden [1]. Measurements of CSF biomarkers are also difficult to be employed in large-scale screening, because of its invasiveness and the harsh requirement for skilled operators [2]. There is a substantial need for less invasive and lower cost biomarkers in the periphery, which could be used in the clinical routine and community screening. Currently, more researchers engage in the discovery of plasma biomarkers to implement the biological definition of AD and to enrich the target population for clinical trials [3, 4].

Most studies focused on the correlations between plasma amyloid-β (Aβ) and clinical or pathologic aspects of AD [5,6,7,8], whereas a few recent researches have shifted the focus to plasma phosphorylated-tau (p-tau) [9,10,11]. Though peripheral measurements of the phosphorylated-tau were still difficult at present because of its low concentration, recent studies have demonstrated that detection of this marker may be promising [3]. It is found that plasma p-tau showed similar trajectory with the CSF p-tau [12]. AD patients had increased levels of p-tau in the plasma, while the combination of plasma and CSF corresponding tau protein could obviously improve diagnostic accuracy [9]. Besides, plasma p-tau and its combination with amyloid were both significantly correlated with tau deposition in the brain [13].

Plasma p-tau181 is currently under consideration to be implemented in the clinical practice, for that it was proved to elevate along with the clinical severity of AD [10]. It also tended to be a sensitive and specific predictor for brain amyloidosis and tau pathology [10, 14], differentiating AD from other neurodegenerative disorders [14]. Yet there lack either CSF/PET information or longitudinal data in previous studies, which limited the full insight into the potential role of plasma p-tau181 in the pathological process of AD. In the present study, we aimed at exploring whether the plasma p-tau181: (1) correlated with amyloid PET, tau PET and FDG PET which represented brain neurodegeneration; (2) differentiated between PET status or across clinical diagnosis in AD continuum; (3) could be used as a screening test for detecting abnormal pathological changes in the brain; (4) could predict pathological progression.

Materials and methods

ADNI database

The Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative (ADNI) is a global and multi-centered research project that actively supports the investigation and development of treatments that slow or stop the progression of AD. Funded as a private-public partnership, ADNI began in 2004, recruiting participants who are followed and reassessed over time. In this study, researchers track the disease progression of AD dementia in the human brain, along with genetic, neuroimaging, biomarkers and clinical information. This longitudinal research was approved by institutional review boards at each site, and written informed consent was obtained on human experimentation at each institution. More detailed information could be sought at http://adni.loni.usc.edu/study-design.

Recruitment criteria for participants

Participants from ADNI were enrolled in this study if they possessed available data as below: (1) plasma p-tau181 data, (2) amyloid, tau, or FDG PET data, (3) clinical, genetic information and neuropsychological assessments. AD patients were diagnosed as with the Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) score of between 20 and 26, a global Clinical Dementia Rating of 0.5 or 1 and a sum-of-boxes Clinical Dementia Rating (CDR-SB) of 1.0–9.0, conforming to the National Institute of Neurological and Communication Disorders/Alzheimer’s Disease and Related Disorders Association criteria [15]. Patients diagnosed as amnestic MCI were those with the MMSE score of between 24 to 30 and a CDR-SB score of at least 0.5. MCI patients were further dichotomized into progressive or stable MCI groups, in which the former patients conversed to AD dementia in two years from the first measurements of plasma p-tau181 whereas the latter patients remained stable during this period. Cognitively normal controls were defined as those who had the MMSE score no less than 24 and a CDR-SB score of 0 or 0.5.

Plasma and CSF biomarker collection and measurement

Plasma p-tau181 data from ADNI was provided by the Clinical Neurochemistry Laboratory, University of Gothenburg, Sweden. Plasma p-tau181 was generated by the Single Molecule array (Simoa) technique, analyzing by an in-house assay that used the combination of two monoclonal antibodies (Tau12 and AT270) [14]. Data of CSF Aβ1–42, t-tau, and p-tau181 were from the Department of Pathology & Laboratory Medicine and Center for Neurodegenerative Diseases Research, Perelman School of Medicine University of Pennsylvania (UPenn). They used the automated Roche Elecsys and cobas e immunoassay analyzer system. These measurements followed a Roche Study Protocol at the UPenn/ADNI Biomarker Laboratory, according to the preliminary kit manufacturer’s instructions and as described in previous studies [1, 16]. Data of plasma Aβ42/40 ratio were provided by the Bateman Lab using a high precision assay with the anti-Aβ mid-domain antibody on the automated immunoprecipitation platform (uploaded on June 2019).

PET imaging acquisition and processing

Data of brain amyloid PET were acquired by the florbetapir (AV-45) tracer, and the summary data are regularly updated on the website of ADNI. The native-space MRI scans of participants were segmented by the Freesurfer (version 4.5.0). The mean uptakes of selected cortical and reference regions were then measured with the florbetapir scans which were applied to the MRI scans, correspondingly. Summary florbetapir standard uptake value ratios (SUVRs) were generated by averaging uptake ratios across four cortical regions (frontal, anterior/posterior cingulate, lateral parietal and lateral temporal regions) and then normalizing it by the reference region (whole cerebellum). Brain tau deposit was measured via the flortaucipir (AV-1451) processing method from the Helen Wills Neuroscience Institute, UC Berkeley and Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory. We chose the composite metaROI of bilateral entorhinal, amygdala, fusiform, parahippocampal, inferior, and middle temporal regions for the tau PET evaluation [17]. To define the hypometabolic regions which were indicative of AD-related pathological metabolic change, FDG PET data were selected. A set of regions of interest (MetaROIs) were developed according to the literature review of FDG-PET studies on AD and MCI [18, 19]. The average counts of FDG PET across angular, temporal and posterior cingulate regions were adopted. Data of structural MRI was obtained by the Siemens Trio scanner and estimates of selected region volume were measured using Free-surfer software. The cutoffs for categories of brain amyloid, tau, and FDG PET were listed as below: 1.11 for florbetapir SUVR, 1.37 for flortaucipir metaROI SUVR [20], and 1.21 for FDG PET [18].

Statistical analysis

All statistical analyses were conducted by R software (version 3.4.4). Characteristics of the cohort were presented as mean (standard deviation, SD) or number (percentage, %) when appropriate. Differences for continuous variables cross groups were assessed by the Kruskal-Wallis test and those for categorical data were evaluated by the chi-square test or Cochran–Mantel–Haenszel test. The Spearman’s rank correlation tested correlations of plasma p-tau181 with amyloid, tau, and FDG PET. The receiver operating curves (ROCs) comparing cohort subsets provided the area under the curves (AUCs) for a diagnosis of amyloid, tau, or FDG PET positivity. AUC, sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value (PPV) and negative predictive value (NPV) at each optimal cutoff value were applied to assess the biomarker performance. Logistic regression model analyses were used when evaluating the diagnostic performance of plasma p-tau181 combined with clinical and genetic information (age, gender, years of education and APOE ɛ4 genotype). Differences between ROCs were tested by the DeLong’s test. ROC curves and the logistic regression (LR) analysis was carried out using the “OptimalCutpoints” and “pROC” packages in R. We also explored whether the relationships between plasma p-tau181 and PET biomarkers were mediated by CSF biomarkers, including Aβ1-42, total tau (t-tau), and p-tau. Mediation analyses were performed with the package “mediation” in R. Effects of CSF biomarkers and plasma p-tau181 on PET biomarkers were tested in the linear regression models, adjusted for age, gender, years of education and APOE ɛ4 genotype. Baron and Kenny proposed the methods which supported the linear regression models fitted [21]. For longitudinal analyses, baseline plasma p-tau181 were roughly dichotomized (PTAU+/PTAU−) by defining the cutoff that could best discriminate AD patients with Aβ-positivity from those normal subjects with Aβ-negativity. The ending events were defined as conversion from Aβ PET− to Aβ PET+, or conversion from FDG PET− to FDG PET+. In longitudinal analyses, we excluded borderline cases and reset the cutoffs that were ±5% from the original cutoffs to avoid drawing conclusions based on borderline cases [22, 23]. Unadjusted Kaplan–Meier plots were constructed to assess the risk of PTAU+/PTAU− groups progressing from PET biomarker negativity to positivity. Besides, we ran univariate and multivariate Cox proportional-hazards models to predict pathological progression. Age, gender, years of education and APOE ɛ4 genotype were included as covariates in the multivariate models. The statistical significance of all tests was set at a two-sided P value <0.05.

Results

Description of the study cohort

Demographic characteristics of the study cohort are summarized in Table 1, including clinical features and APOE genotype. A total of 1189 participants were enrolled, among which 1060 participants had data of amyloid PET, 195 had tau PET and 1085 had FDG PET (Table 1). Participants with abnormal uptake of PET tracer (PET+) presented to be older than those without (P < 0.05). The FDG-PET+ group had a larger proportion of male participants than the FDG-PET− group (P = 0.007), whereas amyloid-PET and tau-PET groups did not show significant difference in gender ratios. All PET+ groups showed significantly higher proportions of APOE ɛ4 carriers and poorer cognition performance, compared to the corresponding PET− groups (Table 1). Amyloid-PET+ and FDG-PET+ groups had more AD patients than PET− participants (28.0% versus 5.0%, and 38.9% versus 4.2%, respectively; P < 0.05, Table 1).

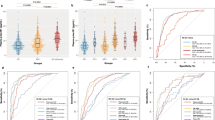

Figure 1 demonstrated mean differences of plasma p-tau181 concentrations between PET groups and among diagnostic groups. Amyloid-PET+ participants had increased levels of plasma p-tau181 than amyloid-PET− individuals (21.6 ± 9.9 versus 14.4 ± 9.9 pg/ml, P < 0.0001; Fig. 1A). Tau-PET+ group showed a higher level of plasma p-tau181 than the tau-PET− group (20.9 ± 7.8 versus 15.5 ± 9.3 pg/ml, P = 0.0003; Fig. 1B). FDG-PET+ individuals also illustrated an elevated concentration compared with those with FDG-PET− (21.4 ± 10.3 versus 16.2 ± 10.1 pg/ml, P < 0.0001; Fig. 1C). AD patients (23.7 ± 8.8 pg/ml) and pMCI subjects (24.4 ± 15.4 pg/ml) had significantly higher levels of plasma p-tau181 than sMCI subjects (17.5 ± 10.9 pg/ml) and CN individuals (17.1 ± 25.4 pg/ml) (P < 0.001), whereas no difference was found between AD and pMCI patients (P > 0.05) (Fig. 1D). Considering amyloid status, individuals with Aβ-PET-positivity had increased plasma p-tau181 compared with those with Aβ-PET-negativity, separately in CN (18.0 ± 7.7 vs. 16.7 ± 30.2 pg/ml), sMCI (20.5 ± 9.7 vs. 13.9 ± 9.3 pg/ml), and pMCI (27.5 ± 16.3 vs. 12.6 ± 4.3 pg/ml) subgroups (P < 0.05; Fig. 1E).

Box plots of plasma p-tau181 concentration between amyloid PET groups (A), tau PET groups (B), FDG PET groups (C), clinical diagnostic groups (D), or clinical classification combined with Aβ status (E). Raw data are presented on the box-and-whisker plot background. The middle line represents the median, and the upper and lower lines represent the first and third quartiles, respectively. Patients with mild cognitive impairment were excluded if they had a follow-up time less than 2 years. CN cognitively normal control, sMCI stable mild cognitive impairment, pMCI progressive mild cognitive impairment, AD Alzheimer’s disease.

Relationships between plasma p-tau181 and PET biomarkers

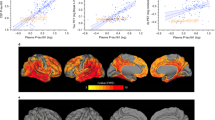

As shown in Fig. 2, plasma p-tau181 was positively correlated with the summary SUVRs of amyloid florbetapir tracer (Spearman ρ = 0.45, P < 0.0001; Fig. 2A) and tau flortaucipir tracer (Spearman ρ = 0.25, P = 0.0003; Fig. 2B). A significantly negative relationship was demonstrated between plasma p-tau181 and FDG glucose metabolism (Spearman ρ = −0.37, P < 0.0001; Fig. 2C). Furthermore, plasma p-tau181 correlated significantly with the cortical amyloid burden in Aβ-positive subjects (Spearman ρ = 0.30, P < 0.0001), while there was no statistical association in Aβ-negative subjects (Spearman ρ = −0.017, P = 0.72). Separately in subjects with or without abnormal tau deposition, no statistical correlations were observed between plasma p-tau181 concentration and metaROI flortaucipir SUVR (Spearman ρ = 0.11, P = 0.59; Spearman ρ = 0.14, P = 0.077, respectively). Among individuals with reduced glucose metabolism, plasma p-tau181 had an inverse link to metaROI FDG glucose metabolism (Spearman ρ = −0.31, P < 0.0001). This link tended to be slightly weaker in those without abnormal brain metabolism (Spearman ρ = −0.21, P < 0.0001).

Scatter fitting curves (A–C) plot the associations of plasma p-tau181 concentration with brain amyloid (A), tau (B), and FDG (C) PET uptakes. Statistical results were generated by the Spearman correlation analyses, and the corresponding curves were roughly smoothed to show directionality. Blue points represent plasma p-tau181 levels of individuals with normal PET uptakes, whereas red points represent those of individuals with abnormal PET uptakes. ROC curves (D–F) illustrate the performance of plasma p-tau181 in discriminating brain pathological changes (D for detecting the abnormal amyloid PET, E for detecting the abnormal tau PET, and F for detecting the abnormal FDG PET). The blue line represents the performance of the clinical model, consisting of age, gender, years of education, and APOE ɛ4 carriage. The red line represents the performance of the adjusted model which combined plasma p-tau181 and the clinical indicators including age, gender, years of education, and APOE ɛ4 carriage. ROC receiver operating characteristic; AUC area under the curve.

Discriminative accuracy of plasma p-tau181 for PET status

ROC analyses for plasma p-tau181 in discriminating brain pathologic changes presented by PET biomarkers were shown in Fig. 2. When we evaluated the diagnostic performance of plasma p-tau181, the ROC curves demonstrated an AUC of 0.755 (95%CI 0.721–0.781) for discriminating Aβ PET-positivity versus PET-negativity, an AUC of 0.728 (95%CI 0.642–0.814) for tau PET, and that of 0.672 (95%CI 0.639–0.705) for FDG PET (Supplementary). In the whole cohort sample, the adjusted models combining plasma p-tau181 and clinical information (age, gender, years of education, and APOE ɛ4 carriage) had moderately better performance for Aβ-PET positivity versus negativity than the model only containing clinical information (AUC 0.814 versus AUC 0.782, DeLong method test P < 0.001; Fig. 2D). Similar, albeit slightly weaker, performance was seen in predicting FDG PET status (AUC 0.708 versus AUC 0.686, DeLong method test P = 0.005; Fig. 2F). The comparison did not reach conventional statistical significance for tau PET status (AUC 0.773 versus AUC 0.733, DeLong method test P = 0.055; Fig. 2E). Concrete diagnostic performance (sensitivity, specificity, PPV, and NPV) of each individual and combined models were shown in the supplementary materials. Furthermore, we explored the performance of plasma p-tau181 combined with Aβ42/40 ratio in a subgroup of 183 subjects. Diagnostic accuracy had slight increments using the combined plasma markers (for Aβ PET status: AUC 0.701 vs. 0.786; for FDG PET status: AUC 0.607 vs. 0.642; no available data for tau PET). Given the small sample size, results of this subgroup should be interpreted with caution.

CSF biomarkers statistically mediates the association between plasma p-tau181 and PET biomarkers

We performed mediation analyses to investigate whether plasma p-tau181 contributed to the prediction of Alzheimer’s pathologies assessed by PET via biomarkers in CSF. We found that CSF biomarkers, including Aβ1–42, p-tau, and t-tau, mediated the effect of plasma p-tau181 on amyloid PET with 29.6%, 30.4%, and 38.0% mediation, respectively (Fig. 3A). Using CSF p-tau or t-tau as the predictors, the effect of plasma p-tau181 on tau PET showed a full mediation (53.9% and 30.9%, respectively), as the effect was reduced from highly significant (P < 0.0001) to reach or near non-significance (P = 0.20, P = 0.046, respectively; Fig. 3B). However, there was no mediating effect of CSF Aβ1–42 (Fig. 3B). Similarly, these three kinds of CSF biomarkers all presented partial mediation for the influence of plasma p-tau181 on FDG PET, with moderate mediated proportions (28.8%, 30.4%, and 25.7%, respectively; Fig. 3C).

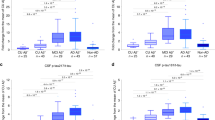

Plasma p-tau181 predicts future amyloid and FDG PET progression

Following the findings that increased plasma p-tau181 appeared to correlated with changes in amyloid, tau, and FDG PET, we further tested whether it could predict the pathological progression in the brain over time. Subsets of individuals with normal amyloid, tau and FDG PET uptake were used to test whether abnormal plasma p-tau181 at baseline could predict a subsequent deterioration in pathologies. Participants with eligible plasma data and clinical diagnosis were enrolled for evaluation of the cutoff point for plasma p-tau181 after the procedures of quality control. Descriptive characteristics of this cohort were described in the Supplementary. ROC analyses of Aβ-positive AD patients versus Aβ-negative normal controls provided the statistically optimal cutoff for plasma p-tau181 (Supplementary). The cutoff for plasma p-tau181 was 18.85 pg/ml with an AUC of 0.840 (95%CI 0.80–0.88; sensitivity 81.1% and specificity 81.6%). This cutoff value had a promising negative predictive value of 86.4%, and a logistic regression AUC of 0.850 after adjusting for age, gender, years of education and APOE genotype.

Participants with normal PET uptake at baseline were included and categorized into two groups by the cut-point of plasma p-tau181 (18.85 pg/ml). A subcohort of 438 individuals who had normal Aβ PET at baseline underwent at least once Aβ PET scan during follow-up periods. Fifty-four subjects (12.3%) converted to Aβ PET-positive over the follow-up period while others remained negative. Among these, individuals with baseline abnormal p-tau181 in the plasma (PTAU+) had a higher risk of conversion from Aβ PET-negativity to PET-positivity (P = 0.0028, Fig. 4A), compared with those with normal plasma levels of p-tau181 at baseline (PTAU−). PTAU+ individuals had a larger proportion rate than the PTAU− group (20.5% vs. 10.3%, Supplementary). A subset of 456 individuals were FDG PET-normal at baseline, of which 81 (17.8%) converted to FDG PET abnormality during the follow-up period. PTAU+ subjects showed an increased risk of conversion to FDG PET abnormality compared with PTAU− individuals (P < 0.0001, Fig. 4B; conversion rate: 30.7% vs. 12.0%, Supplementary).

Unadjusted Kaplan–Meier plots show the risk of conversion from amyloid PET negative to amyloid PET positive (A), and from FDG PET negative to FDG PET positive (B) between baseline plasma p-tau181 status. PTAU−, individuals with baseline plasma p-tau181 concentration less than 18.85 pg/ml; PTAU+, individuals with baseline plasma p-tau181 concentration more than 18.85 pg/ml.

Discussion

In the present study, we aimed to evaluate the potential role of plasma p-tau181 in predicting brain amyloid, tau, and neurodegeneration pathologies presented by the PET technique. We found that the plasma levels of p-tau181 elevated in response to the deterioration of brain pathological changes in the process of AD, which were partly or entirely mediated by CSF biomarkers. Longitudinally, plasma p-tau181 could serve as a progression marker for the Alzheimer’s pathological processes.

Our data comprehensively demonstrated that elevated p-tau181 levels in the periphery were obviously correlated with Alzheimer’s pathological changes in the brain, including abnormal amyloid accumulation, tau deposition and neurodegeneration presented by the decreased glucose metabolism in the brain. Participants with abnormal amyloid, tau burden and hypometabolism in the brain had significantly higher levels of plasma p-tau181, in comparison to those who had normal PET uptakes. Similar findings were proved in other studies which tested plasma biomarkers including p-tau181 [10, 14, 24]. But differently, they lack the evaluation of the possible relationship between plasma p-tau181 and brain neurodegeneration, or chose cortical thickness as the predictor for neuronal injury or neurodegeneration, and reported diverse outcomes. Mielke et al. did not find the possible correlation of plasma p-tau181 with cortical thickness in the AD-featured brain regions [10], whereas the recent study suggested that peripheral p-tau181 level predicted the hippocampal atrophy during a 1-year follow-up period [14]. In our cohort, plasma p-tau181 not only had a cross-sectional relationship with brain neurodegeneration measured by glucose metabolism of metaROIs, but also served as a predictor for neurodegenerative progression. This finding replenished and validated the potential role of plasma p-tau181 as a biomarker for Alzheimer’s pathologies in the brain.

Plasma p-tau181 increased already in the preclinical and prodromal stages of AD prior to the clinical cognitive deterioration, even when measuring plasma samples collected ahead of negative tau PET scans. It has been previously proved that plasma p-tau181 elevated along the Alzheimer’s continuum from preclinical stage to clinical dementia phase [25, 26]. In the present cohort, we categorized the MCI patients into stable MCI (sMCI) and progressive MCI (pMCI) subgroups by whether they conversed to AD dementia in a two-year follow-up period. The clinical subdivision of MCI individuals helped to define the exact distribution of plasma p-tau181 across diagnostic groups. AD and pMCI patients had significantly higher levels of plasma p-tau181 than sMCI patients and cognitively normal controls. However, no difference was found between AD patients and pMCI individuals. Thus, it was reasonable to suspect that the pathological increment of plasma p-tau181 occurred in the early stages of the AD continuum, prior to the clinical cognitive deterioration. To further explore this, we added brain Aβ pathology as a stratification factor for that it was acknowledged as the most featured pathology of AD. In both MCI patients and cognitively normal controls, Aβ-positive individuals proved to have obviously increased levels of plasma p-tau181 than Aβ-negative individuals. Also, MCI patients with Aβ-positivity possessed an increment of peripheral p-tau181 compared to cognitively normal controls with Aβ-positivity. Other cohorts also explored the differences of plasma tau measures by both clinical diagnosis and Aβ PET [10, 14, 27], but they lacked analysis stratified by clinical conversion and observed no statistical difference between the CU A+ and A− groups or the CU and MCI A+ groups [10]. In total, PET-positive individuals all showed significantly elevated concentrations of plasma p-tau181, with approximate increments of 30–50% compared to PET-negative groups. These observations also implemented recent findings showing that plasma biomarker profiles including p-tau181 could predict clinical progression in preclinical and prodromal patients [25].

Both individually and combined with clinical indicators, plasma p-tau181 significantly detected amyloid, tau and neurodegeneration pathologies in the brain. In this cohort, we found the relatively good performance of plasma p-tau181 for distinguishing abnormal uptakes of Aβ, tau and FDG PET from the normal. These performances were similar to or even better than the combined diagnostic capacity of age, gender, education and APOE genotype in discriminating PET abnormality from the normal. Moreover, the combined model consisting of both plasma p-tau181 and clinical indicators proved to be more accurate for Alzheimer’s pathological definition than the model which merely had clinical information. In our cohort, the predictive accuracy of plasma p-tau181 for increased brain amyloid burden was very close to that from the Mayo Clinic data [10], suggesting a stable discriminative performance of plasma p-tau181 in different cohorts. We also found that plasma p-tau181 could detect abnormal tau deposition with moderate accuracy. This finding was in line with the recent studies, which investigated the usefulness of plasma p-tau181 for differential diagnosis [13, 25]. Janelidze et al. conducted ROC analyses separately in Braak I-IV ROI and Braak V-VI ROI [28]. Compared with our cohort, their study reported slightly better diagnostic performance of plasma p-tau181 in the Braak I-IV ROI (AUC 0.86, 95%CI 0.80–0.92) which tends to represent the early stage of tau pathology process in AD [28]. And the diagnostic capacity demonstrated to grow even larger in the Braak V-VI ROI (AUC 0.90, 95%CI 0.84–0.96) which indicated more severe tau pathology [28]. The diagnostic performance of plasma p-tau181 in our cohort was similar to that of Park et al., with both high sensitivity (AUC 0.731, sensitivity 93.33%) [13]. Besides, plasma p-tau181 showed moderate diagnostic ability in detecting hypometabolism of metaROIs in the brain. When combined with plasma β-amyloid, the diagnostic performance of plasma p-tau181 had only slight increase in detecting cerebral Alzheimer’s pathologies. These results were similar to a previous study, which provided that combination of plasma tau and β-amyloid might be slightly better in predicting brain tau pathology and neurodegeneration [13]. These findings indicated that though single plasma p-tau181 might not be the most preferred approach for AD, it was highly efficient in detecting AD pathology. However, considering the small sample size in both ours and the previous study [13], comparisons of plasma p-tau181 and its combination with other plasma markers are needed to be explored in more large, multi-centered studies in the future. Additionally, in part or in whole, we found that pathological changes of amyloid, tau in CSF outstandingly mediated the role of peripheral p-tau181 in detecting Alzheimer’s pathologies in the brain. These findings also supported the previously published points of view that the breakdown or dysfunction of the blood-brain barrier was associated with the pathogenesis of complex multifactorial diseased which included AD [29, 30]. All these findings indicated an exciting role of peripheral p-tau181 for detecting Alzheimer’s pathologies in the central nervous system.

Furthermore, our previous study has demonstrated that the plasma p-tau181 could be utilized as a progression marker for clinical conversion and cognitive decline [31], and the present findings proved that it was also specific for the AD pathophysiological processes. Individuals with abnormal plasma p-tau181 levels were at higher risk of deterioration of brain amyloidosis and neurodegeneration exceeding the critical boundaries. Due to long time intervals between plasma samples and tau PET scans in the vast majority of participants, survival analyses were not conducted for tau PET conversion. Additionally in a recent study by our team, we observed that plasma p-tau181 increased on the single patient level over time as the disease progressed [32]. It was also confirmed that plasma p-tau181 was longitudinally correlated with AD-related CSF and PET neuroimaging biomarkers, both in the whole population or in subgroups defined by ATN classifications and cognitive status [32]. Together, these findings supported the effectiveness of plasma p-tau181 in monitoring pathological changes during the course of AD. Previous studies mainly focused on the conversion of clinical outcomes [25], but lack further insight into the role of plasma p-tau181 in predicting the pathological changes of AD. Our study filled the gap in this area, and suggesting that the plasma p-tau181 had the potential to serve as a sufficient biomarker for tracking the Alzheimer’s pathological process. Future studies on tau PET are warranted to expand validation results.

The present study has limitations. Though plasma biomarker profiles have advantages over PET or CSF measurements, at present, advance in this field was confined due to different experimental methods, clinical population across laboratories and lack of reproductivity. Our study cohort did not have individuals due to non-AD dementia, which hampered the assessments of plasma p-tau181 in discriminating AD versus other kinds of dementia [3, 11]. There also lack sufficient longitudinal data to further evaluate the potential role of plasma p-tau181 for predicting brain tau deposits measured by PET. Besides in the present cohort, only 24 subjects were defined as tau PET-positivity, which limited the precise evaluation in detecting brain tau deposition. Given the small sample size, more comprehensive research in larger cohorts are required to define the diagnostic potential of plasma p-tau181 for brain tau pathology.

In total, we suggested that plasma p-tau181 could be utilized as the preliminary and practical test for the detection of Alzheimer’s pathology. This measurement could help ruling out the pathological definition of AD, and guide the population screening and therapy monitoring for disease-modifying trials. Future validation research is demanded in larger, more diverse population to confirm these findings and provide more insight into this plasma biomarker over longer periods of disease progression.

Data availability

Data used in the preparation of this article were obtained from the ADNI database (adni.loni.usc.edu), which is easily available for the research public.

References

Hansson O, Seibyl J, Stomrud E, Zetterberg H, Trojanowski JQ, Bittner T, et al. CSF biomarkers of Alzheimer’s disease concord with amyloid-β PET and predict clinical progression: a study of fully automated immunoassays in BioFINDER and ADNI cohorts. Alzheimers Dement. 2018;14:1470–81.

Jack CR Jr, Bennett DA, Blennow K, Carrillo M, Dunn B, Haeberlein SB, et al. NIA-AA Research Framework: toward a biological definition of Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimers Dement. 2018;14:535–62.

Tatebe H, Kasai T, Ohmichi T, Kishi Y, Kakeya T, Waragai M, et al. Quantification of plasma phosphorylated tau to use as a biomarker for brain Alzheimer pathology: pilot case-control studies including patients with Alzheimer’s disease and down syndrome. Mol Neurodegener. 2017;12:63.

O’Bryant SE, Mielke MM, Rissman RA, Lista S, Vanderstichele H, Zetterberg H, et al. Blood-based biomarkers in Alzheimer disease: Current state of the science and a novel collaborative paradigm for advancing from discovery to clinic. Alzheimers Dement. 2017;13:45–58.

Doecke JD, Pérez-Grijalba V, Fandos N, Fowler C, Villemagne VL, Masters CL, et al. Total Aβ(42)/Aβ(40) ratio in plasma predicts amyloid-PET status, independent of clinical AD diagnosis. Neurology. 2020;94:e1580–e1591.

Vergallo A, Mégret L, Lista S, Cavedo E, Zetterberg H, Blennow K, et al. Plasma amyloid β 40/42 ratio predicts cerebral amyloidosis in cognitively normal individuals at risk for Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimers Dement. 2019;15:764–75.

Schindler SE, Bollinger JG, Ovod V, Mawuenyega KG, Li Y, Gordon BA, et al. High-precision plasma β-amyloid 42/40 predicts current and future brain amyloidosis. Neurology. 2019;93:e1647–e1659.

Pérez-Grijalba V, Arbizu J, Romero J, Prieto E, Pesini P, Sarasa L, et al. Plasma Aβ42/40 ratio alone or combined with FDG-PET can accurately predict amyloid-PET positivity: a cross-sectional analysis from the AB255 Study. Alzheimers Res Ther. 2019;11:96.

Fossati S, Cejudo JR, Debure L, Pirraglia E, Sone JY, Li Y, et al. Plasma tau complements CSF tau and P-tau in the diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimers Dement (Amst). 2019;11:483–92.

Mielke MM, Hagen CE, Xu J, Chai X, Vemuri P, Lowe VJ, et al. Plasma phospho-tau181 increases with Alzheimer’s disease clinical severity and is associated with tau- and amyloid-positron emission tomography. Alzheimers Dement. 2018;14:989–97.

Lin CH, Yang SY, Horng HE, Yang CC, Chieh JJ, Chen HH, et al. Plasma biomarkers differentiate Parkinson’s disease from atypical parkinsonism syndromes. Front Aging Neurosci. 2018;10:123.

Palmqvist S, Insel PS, Stomrud E, Janelidze S, Zetterberg H, Brix B, et al. Cerebrospinal fluid and plasma biomarker trajectories with increasing amyloid deposition in Alzheimer’s disease. EMBO Mol Med. 2019;11:e11170.

Park JC, Han SH, Yi D, Byun MS, Lee JH, Jang S, et al. Plasma tau/amyloid-β1-42 ratio predicts brain tau deposition and neurodegeneration in Alzheimer’s disease. Brain. 2019;142:771–86.

Karikari TK, Pascoal TA, Ashton NJ, Janelidze S, Benedet AL, Rodriguez JL, et al. Blood phosphorylated tau 181 as a biomarker for Alzheimer’s disease: a diagnostic performance and prediction modelling study using data from four prospective cohorts. Lancet Neurol. 2020;19:422–33.

McKhann GM, Knopman DS, Chertkow H, Hyman BT, Jack CR Jr, Kawas CH, et al. The diagnosis of dementia due to Alzheimer’s disease: recommendations from the National Institute on Aging-Alzheimer’s Association workgroups on diagnostic guidelines for Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimers Dement. 2011;7:263–9.

Bittner T, Zetterberg H, Teunissen CE, Ostlund RE Jr, Militello M, Andreasson U, et al. Technical performance of a novel, fully automated electrochemiluminescence immunoassay for the quantitation of β-amyloid (1-42) in human cerebrospinal fluid. Alzheimers Dement. 2016;12:517–26.

Jack CR Jr, Wiste HJ, Therneau TM, Weigand SD, Knopman DS, Mielke MM, et al. Associations of amyloid, tau, and Neurodegeneration Biomarker Profiles With Rates Of Memory Decline Among Individuals Without Dementia. Jama. 2019;321:2316–25.

Landau SM, Harvey D, Madison CM, Reiman EM, Foster NL, Aisen PS, et al. Comparing predictors of conversion and decline in mild cognitive impairment. Neurology. 2010;75:230–8.

Landau SM, Harvey D, Madison CM, Koeppe RA, Reiman EM, Foster NL, et al. Associations between cognitive, functional, and FDG-PET measures of decline in AD and MCI. Neurobiol Aging. 2011;32:1207–18.

Meyer PF, Binette AP, Gonneaud J, Breitner JCS, Villeneuve S. Characterization of Alzheimer disease biomarker discrepancies using cerebrospinal fluid phosphorylated tau and AV1451 positron emission tomography. JAMA Neurol. 2020;77:508–16.

Baron RM, Kenny DA. The moderator-mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1986;51:1173–82.

McRae-McKee K, Udeh-Momoh CT, Price G, Bajaj S, de Jager CA, Scott D, et al. Perspective: clinical relevance of the dichotomous classification of Alzheimer’s disease biomarkers: Should there be a “gray zone”? Alzheimers Dement. 2019;15:1348–56.

Yu JT, Li JQ, Suckling J, Feng L, Pan A, Wang YJ, et al. Frequency and longitudinal clinical outcomes of Alzheimer’s AT(N) biomarker profiles: A longitudinal study. Alzheimers Dement. 2019;15:1208–17.

Thijssen EH, Joie LA, Wolf R, Strom A, Wang A, Iaccarino P. L. et al. Diagnostic value of plasma phosphorylated tau181 in Alzheimer’s disease and frontotemporal lobar degeneration. Nat Med. 2020;26:387–97.

Janelidze S, Mattsson N, Palmqvist S, Smith R, Beach TG, Serrano GE, et al. Plasma P-tau181 in Alzheimer’s disease: relationship to other biomarkers, differential diagnosis, neuropathology and longitudinal progression to Alzheimer’s dementia. Nat Med. 2020;26:379–86.

Yang CC, Yang CC, Chiu MJ, Chen TF, Chang HL, Liu BH, Yang SY. Assay of plasma phosphorylated tau protein (Threonine 181) and total tau protein in early-stage Alzheimer’s disease. J Alzheimers Dis. 2018;61:1323–32.

Mattsson-Carlgren N, Andersson E, Janelidze S, Ossenkoppele R, Insel P, Strandberg P, et al. Aβ deposition is associated with increases in soluble and phosphorylated tau that precede a positive Tau PET in Alzheimer’s disease. Sci Adv. 2020;6:eaaz2387.

Cho H, Choi JY, Hwang MS, Kim YJ, Lee HM, Lee HS, et al. In vivo cortical spreading pattern of tau and amyloid in the Alzheimer disease spectrum. Ann Neurol. 2016;80:247–58.

Zhao Z, Nelson AR, Betsholtz C, Zlokovic BV. Establishment and dysfunction of the blood-brain barrier. Cell. 2015;163:1064–78.

Sweeney MD, Zhao Z, Montagne A, Nelson AR, Zlokovic BV. Blood-brain barrier: from physiology to disease and Back. Physiol Rev. 2019;99:21–78.

Shen, XN, Li, JQ, Wang, HF, Li, HQ, Huang, YY, Yang, YX, et al. Plasma amyloid, tau, and neurodegeneration biomarker profiles predict Alzheimer’s disease pathology and clinical progression in older adults without dementia. Alzheimers Dement (Amst). 2020;12:e12104.

Chen SD, Huang YY, Shen XN, Guo Y, Tan L, Dong Q, et al. Longitudinal plasma phosphorylated tau 181 tracks disease progression in Alzheimer’s disease. Transl Psychiatry. 2021;11:356.

Acknowledgements

Data used in preparation for this article were obtained from the Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative (ADNI) database (adni.loni.usc.edu). As such, the investigators within the ADNI contributed to the design and implementation of ADNI and/or provided data but did not participate in the analysis or writing of this report. The authors express appreciation to contributors of Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative (ADNI) database. A complete listing of ADNI investigators can be found at: http://adni.loni.usc.edu/wp-ontent/uploads/how_to_apply/ADNI_Acknowledgement_List.pdf.

Funding

This study was supported by grants from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (9184910220, 91849126, 81571245, and 81771148), the National Key R&D Program of China (2018YFC1314700), Shanghai Municipal Science and Technology Major Project (No.2018SHZDZX01), ZHANGJIANG LAB, and Shanghai Center for Brain Science and Brain-Inspired Technology, Tianqiao and Chrissy Chen Institute, and the State Key Laboratory of Neurobiology and Frontiers Center for Brain Science of Ministry of Education, Fudan University. Data collection and sharing for this project was funded by the Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative (ADNI) (National Institutes of Health Grant U01 AG024904) and DOD ADNI (Department of Defense award number W81XWH-12-2-0012). Data used in the preparation for this article were derived from the ADNI database (http://adni.loni.usc.edu/). The authors express appreciation to contributors of Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative (ADNI) database. ADNI is funded by the National Institute on Aging, the National Institute of Biomedical Imaging and Bioengineering, and through generous contributions from the following: AbbVie, Alzheimer’s Association; Alzheimer’s Drug Discovery Foundation; Araclon Biotech; BioClinica, Inc.; Biogen; Bristol-Myers Squibb Company; CereSpir, Inc.; Cogstate; Eisai Inc.; Elan Pharmaceuticals, Inc.; Eli Lilly and Company; EuroImmun; F. Hoffmann-La Roche Ltd and its affiliated company Genentech, Inc.; Fujirebio; GE Healthcare; IXICO Ltd.; Janssen Alzheimer Immunotherapy Research & Development, LLC.; Johnson & Johnson Pharmaceutical Research & Development LLC.; Lumosity; Lundbeck; Merck & Co., Inc.; Meso Scale Diagnostics, LLC.; NeuroRx Research; Neurotrack Technologies; Novartis Pharmaceuticals Corporation; Pfizer Inc.; Piramal Imaging; Servier; Takeda Pharmaceutical Company; and Transition Therapeutics. The Canadian Institutes of Health Research is providing funds to support ADNI clinical sites in Canada. Private sector contributions are facilitated by the Foundation for the National Institutes of Health (www.fnih.org). The grantee organization is the Northern California Institute for Research and Education, and the study is coordinated by the Alzheimer’s Therapeutic Research Institute at the University of Southern California. ADNI data are disseminated by the Laboratory for Neuro Imaging at the University of Southern California.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Consortia

Contributions

JTY: conceptualization and design of the study, analysis and interpretation of data and revision of the manuscript. XNS and YYH: conceptualization and design of the study, collection and analysis of the data, drafting and revision of the manuscript. SDC and YG: collection and analysis of the data, drafting and revision of the manuscript. LT and QD: drafting and revision of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The study was approved by the Partners Healthcare Institutional Review Board (IRB), and written informed consent was obtained from all participants prior to initiation of any study procedures in accordance with IRB guidelines.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Shen, XN., Huang, YY., Chen, SD. et al. Plasma phosphorylated-tau181 as a predictive biomarker for Alzheimer’s amyloid, tau and FDG PET status. Transl Psychiatry 11, 585 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41398-021-01709-9

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41398-021-01709-9