The rejuvenation of urban community in China under COVID-19

- 1Department of Architecture and Built Environment, University of Nottingham Ningbo China, Ningbo, China

- 2School of International Studies, University of Nottingham Ningbo China, Ningbo, China

The persistent COVID-19 pandemic has continuously brought the basic level of urban governance to the forefront. Urban community governance in China involves both state-led and civil society-led governance. Whilst previous studies have noted the weak civil society and delocalization in modern China, recent research reveals the re-localization trend shown during the pandemic. In this brief research report, we seek to provide a detailed account of the hyper-local dynamism within civil society in responding to the public health emergency, focusing on the thriving spontaneous groups in Shanghai during the COVID-19 outbreak in March and April 2022. By dissecting the multi-level, multi-actor governance, we reveal the significant roles played by spontaneous groups in complementing state-led governance and in building united urban communities in combatting the worst effects of COVID-19. We outline the types and organizational structure of various spontaneous groups. We also critically reflect on their implications and potential in advancing urban community governance in China. We argue that there is an imperative need to further explore how these spontaneous groups can catalyze transformative changes that can for example empower grassroots actors and motivate wider public participation in community decision-making.

Introduction

While most countries are pushing ahead with reopening travel and easing restrictions, the strict Dynamic Zero-COVID policy1 and the repeated outbreaks continue to challenge China's populous cities and their governance. As of mid-May 2022, the lock-down of Shanghai still makes worldwide headlines and the city's responses to the crisis have been consistently tested. As opposed to the government's struggles to fight the massive infections2 and to meet the basic daily demands of its citizens, it is observed that residents in Shanghai have been drawn together spontaneously to form self-organizing groups to provide mutual aid and support. This new hyper-local dynamism within the society is significant, playing a key role in combating the worst effects of COVID-19. Its emergence and influences (both short-term under the outbreak and long-term beyond the pandemic) on China's urban community governance are thus worth pursuing.

Within the growing literature on urban community governance in China in recent years, there are many studies pointing out the delocalization processes (Zheng, 2016), the atomization of individuals and urban communities (Ren et al., 2015), the disappearance of “nearby” (Xiang, 2021), and the weak civil society in Chinese cities (Huang et al., 2018) due to the technology-led modernization process under the unique party-state system and also due to the reconstruction of a large number of urban communities and the commercialization of housing since the 1990s. The lack of collective experience and memory of living together makes the creation of community identity in Chinese urban neighborhoods very difficult (Zheng, 2016). Local residents are also found to lack awareness, willingness and/or opportunities to participate in public affairs and community governance, especially in policy-making process (Zhang et al., 2018). In this paper, however, we seek to draw attention to the rejuvenation of community in urban China under the COVID-19 pandemic, represented by the thriving spontaneous groups led by the civil society. Here, what we discuss as community differs from the Chinese term “she-qu” which is geographically defined living area and the “base unit” of urban administration and structure (Bray, 2009; Heberer, 2019). Instead, we refer it broadly to a functionally autonomous social unit formed by interacting human actors with commonality such as mutual interests, spatial proximity, common identity, and shared values or norms (McMillan and Chavis, 1986; Bhattacharyya, 2004).

The remainder of this brief research report will be divided into four sections. The following Section Urban community governance in China and the methodology of this study begins with a brief analysis of the basic structure and key features of urban community governance in China, before elaborating the significance and methodology of this research. Following this, Section The thriving community in Shanghai under the COVID-19 outbreak looks into Shanghai during its recent COVID-19 outbreak and explores the reaction and operation of different actors and organizations, as well as their cooperation and coordination, in the community level, with a specific focus on the emerging citizen-led spontaneous groups. In Section Challenges, potential and implications of the emerging spontaneous groups, we critically discuss the rise of urban community during the pandemic as demonstrated by the spontaneous groups, and Section Conclusion concludes with reflection.

Urban community governance in China and the methodology of this study

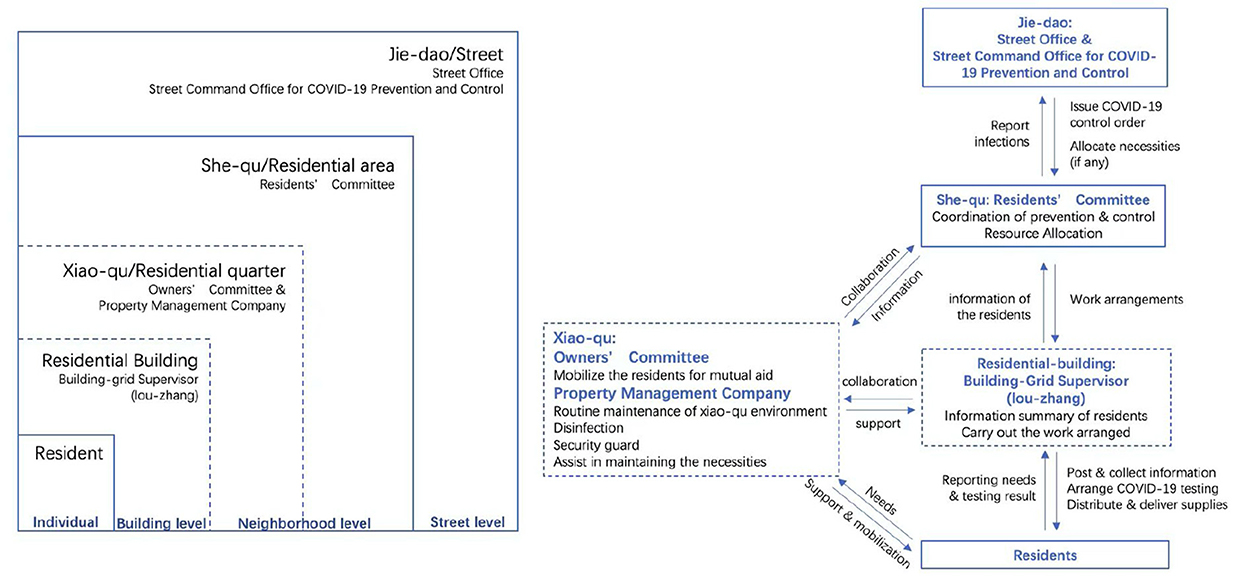

Despite the presence of a strong state in public affairs, contemporary urban community governance in China involves both state and non-state actors. The state-led community governance is typically top-down, evolving from the previous system based on the socialist work unit (danwei) under the planned economy and the strict household registration system (hukou), to current urban grid management system (wang-ge-hua-guan-li)3, which recognizes the increasing mobility and heterogeneity in urban society and is supported by the rapid development of information and communication technology (Bray, 2006; Wei et al., 2021). The administrative structure is hierarchical, from the municipal (shi) and district levels (qu) to the street level (jie-dao), and then to the neighborhood level (she-qu). In the street level, the Street Office (jie-dao-ban-shi-chu) as a governmental agency is the basic unit that connects the residents with the local governments. The responsibility of the Street Office includes collecting and presenting public opinions to relevant governmental departments (Wan, 2015) and assisting local governmental sectors' in policy implementation and in guiding and supervising the daily operation of the Residents' Committees (ju-min-wei-yuan-hui). The Residents' Committees (RC) is described as “a mass organization with the members democratically elected by residents”.4 However, despite being officially defined as a grassroots, self-governing organization at the neighborhood level, key members of the RC are usually designated by the Street Office, and the election process is found to be highly political (Wan, 2015). Now fused with the grid system which was firstly introduced in Beijing in 2003 and officially launched nationwide in 2013 (Xiang, 2021), the RC's key personnel are leading the grid management at the basic level.

In comparison, the civil society-led governance at the community level has a less rigid institutional structure and greater flexibility in organization and operation. It often involves a multiplicity of urban actors, which can be broadly divided into three categories: 1) homeowners' associations of residential quarter (xiao-qu) and the property management companies employed by them; 2) civil society organizations (CSOs) such as non-profit organizations (NPOs), non-governmental organizations (NGOs) and philanthropic foundations; and 3) residents-led spontaneous groups. It is to be noted that these three types of actors are mainly demarcated by their leading actor groups, and they are not exclusive nor exhaustive. For example, the residents-led spontaneous groups can be composed of homeowners, tenants, members of CSOs, and even government officials. The three groups of actors are briefly introduced below.

The private housing reform started in 1998 led to the rise of commercial housing industry in China (Wang and Murie, 2000). As early as 1998, the owners at Liwan Square in Guangzhou, a luxurious apartment at that time, successfully initiated an election of their Owners' Committee (OC), which heralds the booming of OC in Chinese cities and demonstrates a step toward the self-autonomy of the property owners in managing their own properties (Qu, 2016), especially in metropolises. Taking Shanghai as an example, there are more than 13,000 residential quarters (xiao-qu), of which more than 90% have established OCs (Southern Weekend., 2021). Typically, an OC is formed by private property owners which in turn act in their best collective interest by not only supervising the service quality of the property management company designated by the owners, but also acting on the owners' behalf in dealing with any disputes that may arise between the property owners and the property management company (ibid.). Although the government's intervention in civil affairs is almost in every aspect (Qu, 2016), the OC increasingly becomes a key self-managed organization in China's urban society.

Meanwhile, in the past two decades, CSOs have proliferated in urban China5 and play an increasingly important role in filling the void of the state-led top-down urban community governance in China and in balancing the role of the state and the rights of citizens. During the previous pandemic - the Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome (SARS) outbreak – in the spring of 2003, CSOs in China demonstrated their value to society by responding to the crisis swiftly and effectively by, for example, establishing counseling hotlines for the public and for front-line medical works, and disseminating SARS prevention information, disinfectant, and masks among migrant workers and their families (Bentley, 2004). More recently, CSOs also play a significant role in facilitating sustainable and just urban transitions and in cultivating and supporting community entrepreneurship and activities (Shieh and Friedmann, 2008; Chen and Qu, 2020). The Nature Conservancy, for instance, has been promoting green roof and community garden developments in Shenzhen through pilot projects since 2018 (Xie, 2022).

Comparing to the OC and CSOs, spontaneous groups formed by voluntary residents often rise in emergencies or disasters (thus also termed as “emergent groups”) (Dynes, 1970). These groups often have no pre-existing structure (Petrescu-Prahova and Butts, 2005), and they appear as responses to the task needs in cases that existing hierarchical structures or organizations alone cannot cope with the emergent and unpredictable needs, and to the coordination needs when information sharing, coordination, and control among numerous organizations become difficult (Dynes, 1970). For example, during the 2008 Wenchuan earthquake in China, local spontaneous volunteers provided on-site assistances such as search and rescue operations, medical support, logistical support and even post-disaster reconstructions (Jiang, 2009). Recently, more and more spontaneous groups have arisen in urban China, especially in megacities, leading collective actions to protect the public interests, defending a safe and healthy living environment (Chen and Qu, 2020; Zhang et al., 2020).

Whilst the above descriptions briefly present the current configuration of China's urban community governance (both the state-led and non-state-led), it is worth noting that urban community governance in China is constantly evolving. Since 2013, China has been promoting the construction of collaborative urban community governance system, which emphasizes self-governance and public participation among urban residents (CCCPC State Council, 2017; Guo and Yin, 2019). Shanghai has been a pioneer in advancing the movement: it introduced the grid management system as early as in 2004 and it has promoted the “Autonomous Community” (she-qu-zi-zhi) construction since 2014, encouraging self-organizing initiatives and public engagement in community governance (Guo and Yin, 2019). Nevertheless, the most recent COVID-19 outbreak poses unprecedented challenges to the metropolis' governance system. As a key financial, manufacturing and shipping hub, Shanghai took a precise and targeted prevention and control approach (jing-zhun-fang-yi) at the beginning of the outbreak. However, with record high numbers of local daily infections and the persistent emphasis on zero-COVID target from the central government, Shanghai has eventually entered a two-month “static management-style restriction”. Amid the actual lockdown, difficulties of community governance in Shanghai have grown, ranging from controlling the spread of infection to organizing mandatory mass testing, and to maintaining essential food supply for its 26 million residents. How local administrations, social organizations and residents responded to the ever-mounting challenges and how urban community governance adjusted to address the crisis are important questions worthy of inquiry.

This research is drawn on an intensive investigation conducted during the COVID-19 outbreak in Shanghai from March to May in 2022. Data was collected through an extensive review of documents, which include governmental policies/notices, media reports, public documents circulated among citizens, and posts and discussions on social medias such as Weibo and WeChat. We also attained first-hand information through interviews with 21 residents that were directly affected by the outbreak, as well as 12 citizen volunteers who were actively engaged in organizing or volunteering in the spontaneous groups and volunteer teams. To better understand the organization and operation of various spontaneous groups (including both online networks and off-line groups), we also conducted focus group discussions with 5 members of a local NPOs based in Shanghai – the Big Fish Community Design Center – in April 2022. As we shall see in our analysis below the pandemic has sparked the revival of local social connections and grassroots spontaneous groups that complement state-led urban community governance amidst the crisis.

The thriving community in Shanghai under the COVID-19 outbreak

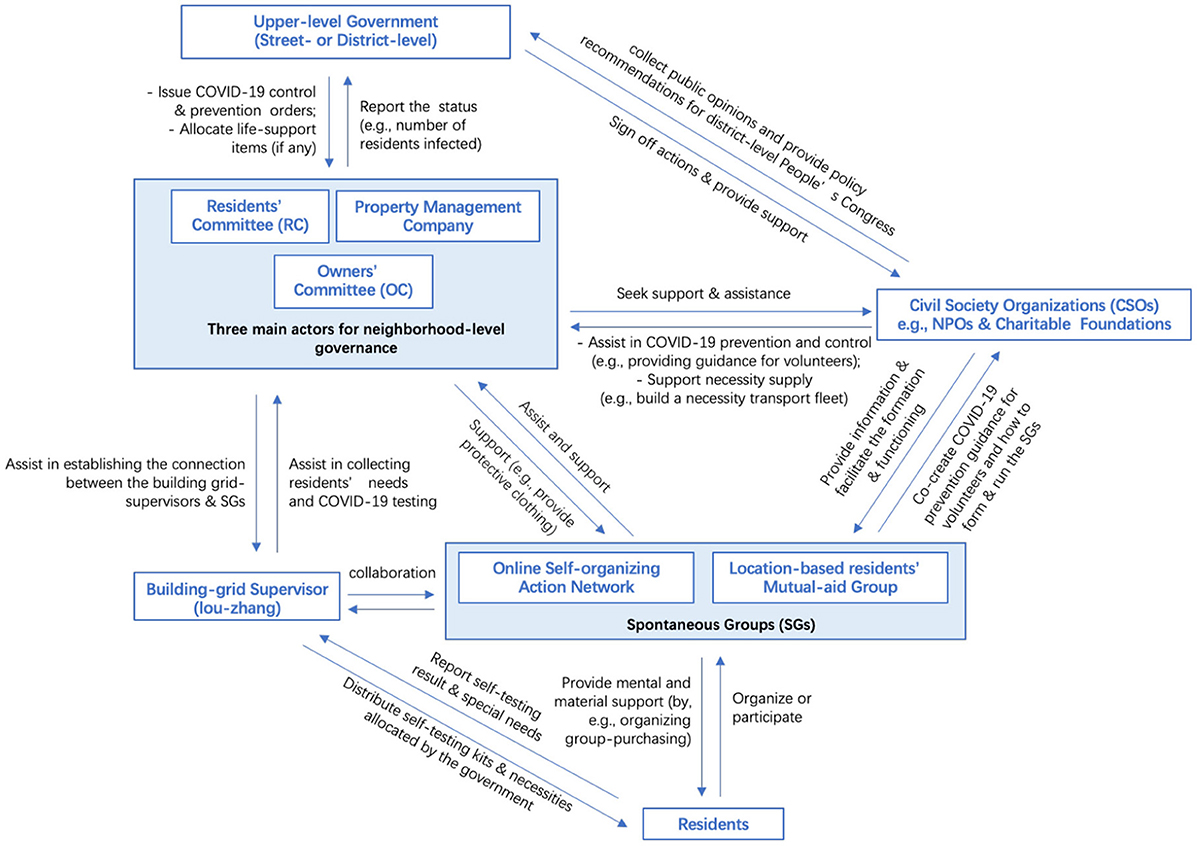

In this session we turn to the community governance in Shanghai under the recent COVID-19 outbreak, exploring the emerging community in response to the most severe health emergency of the metropolis. Figure 1 depicts the roles of the key urban actors in responding to the outbreak, who routinely engage in urban community governance in Shanghai. As can be seen, both the governmental agencies as well as the non-governmental actors (i.e., the OC and the property management company) quickly spread out their capacities and resources to carry out non-regular tasks. The RC, for example, was responsible for the overall coordination of COVID-19 prevention and control as well as the provision of daily necessities. Under the overall guidance of the RC, the building-grid supervisor (lou-zhang), who is often appointed directly by the RC, as well as the OC and the property management company, all act to assist the implementation of the prevention and control measures, which include testing arrangement, distributing the necessities, and mobilizing local residents for mutual aid.

Figure 1. The community governance structure in Shanghai during the outbreak of COVID-19 (1. The key personnel of the RC are often the grid head (she-qu level) and grid manager (xiao-qu level) of the grid management system. 2. Some commercial apartments that do not belong to any xiao-qu and some old xiao-qu that do not have OC or property management company are under direct management by the she-qu; and in some residential buildings, there are no building-grid supervisors).

Nevertheless, due to the lack of experience and capacity in handling the excessive amount of work, these actors soon found themselves overstretched. The strict lockdown has led to the massive closure of offline supermarkets and stores and the severe disruptions of grocery delivery services for online shopping6. The municipal government and local administrations were then required to take on the heavy duties of distributing daily necessities in addition to the COVID-19 prevention and control (Cai, 2022). Under such circumstances, CSOs, especially NPOs, that operate in Shanghai quickly responded by launching online public forums for discussing the emerging challenges and possible solutions. Opinions collected were then translated into policy recommendations provided to district-level People's Congress, informing government's responses and actions. Besides, CSOs also acted to provide guidance for local citizens on not only self-protection but also on how to form self-aid teams of their own neighborhoods. For example, the Bottle Dream, a social innovation enterprise based in Shanghai, produced a “Volunteer Work Manual of Community Pandemic Prevention in Shanghai”, providing guidance for volunteers to organize and facilitate self-aid and mutual-aid in their own neighborhoods, which includes promoting information communication, assisting PCR tests, ordering and distributing food and so forth7. Besides providing in-direct support, some CSOs also actively engage in the organization of spontaneous mutual-aid groups by having members leading some pilots. In the meantime, various spontaneous groups were quickly formed, both online as self-organizing action networks and off-line as location-based residents' mutual-aid groups. Collaborating with one another, the spontaneous groups and the CSOs, as well as the RC, OC, and property management company, are forming a new community governance network (Figure 2).

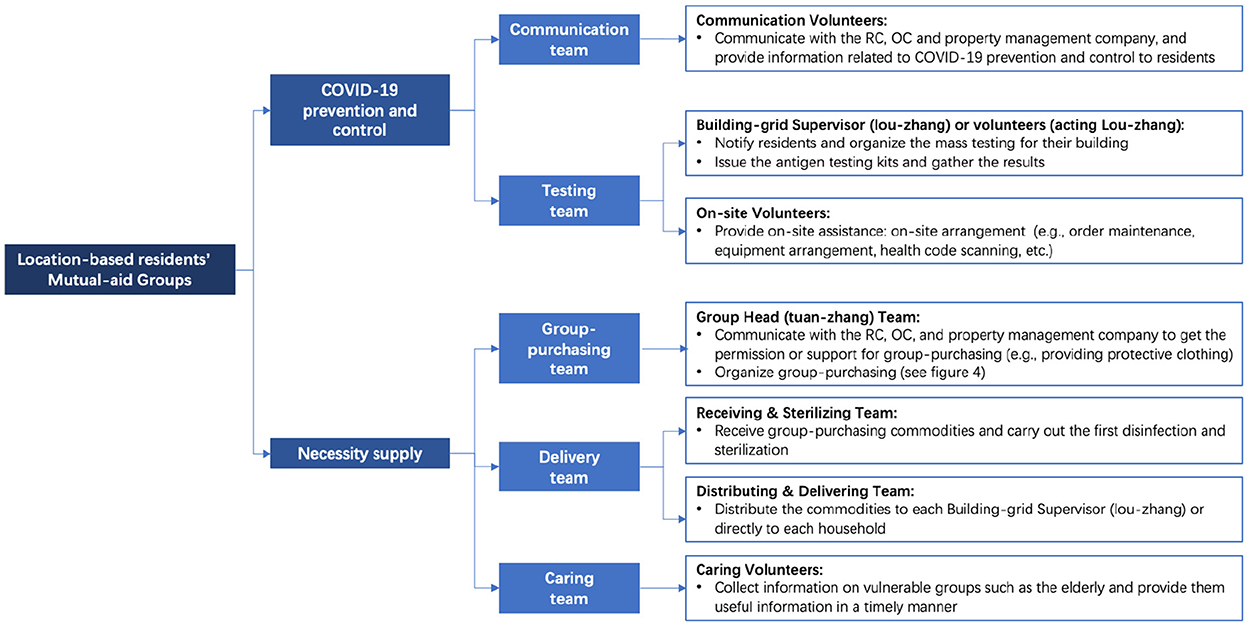

Mainly initiated by members of the CSOs based in Shanghai, the online self-organizing action networks' main activities include: conducting online survey and providing information and even psychological counseling for people in need; organizing online activities such as theater and poetry reading event; and developing toolkits for volunteers and residents directly. The off-line location-based residents' mutual-aid groups are mainly initiated by voluntary residents through WeChat – a popular instant-messing app. Members often live in the same building, or neighborhood or street. These groups assist other state and non-state actors (including RC, OC and the property management) in COVID-19 prevention and control, especially in necessity supply through organizing group-purchasing activities (Figure 3).

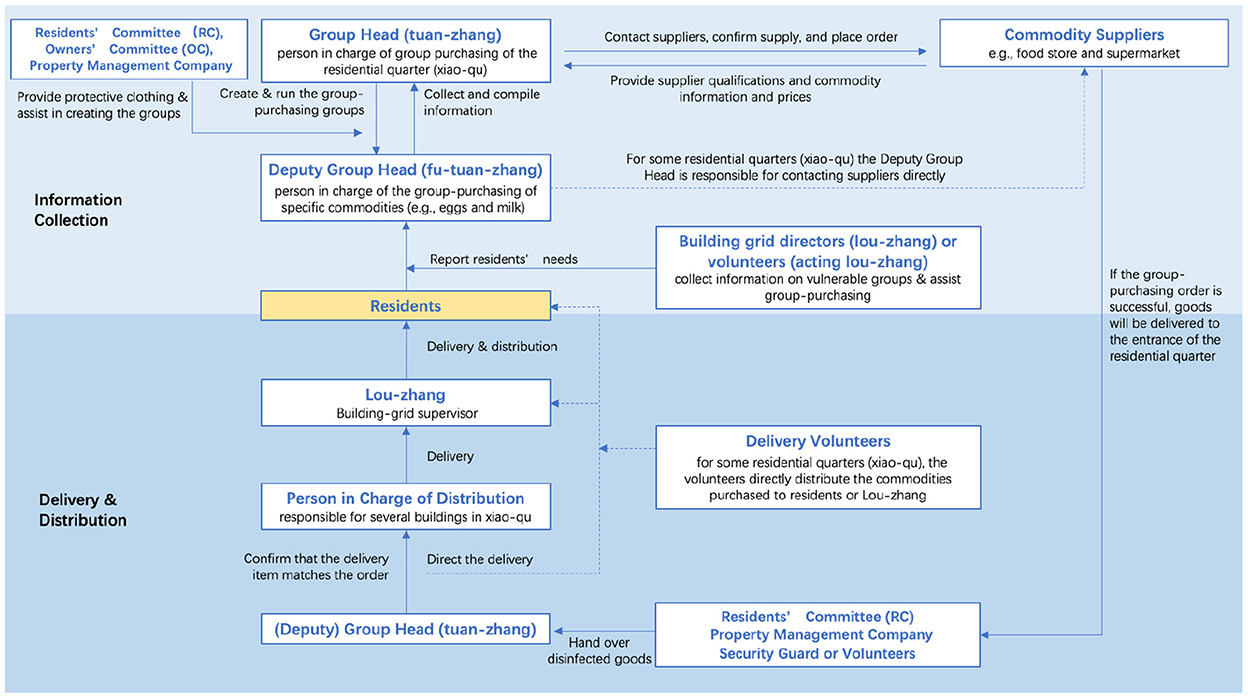

Despite the lack of a pre-existing structure and given guidance, most of the residents' mutual-aid groups managed to quickly form their architecture based on the division of tasks and centered around tuan-zhang (the leader of the group-purchase activity) (as illustrated in Figure 4). Tuan-zhang is mainly responsible for contacting external suppliers; cooperating with the RC, OC, and property management company; recruiting volunteers; and setting up key contacts and leaders in different steps of group-purchasing, including information collection, disinfection, and delivery and distribution. Though spontaneously formed by volunteers and often joined by residents living in the same building or residential quarters, these groups work closely with other actors, supporting group-purchasing to meet the daily needs of residents within the control zone, significantly alleviating the pressure for the local administrations.

Moreover, these mutual-aid groups have shown immense solidarity and soon brought those argued to be atomized residents and urban communities together, forming a close network that gradually developed into a united community. Within the community, members exchange information and materials, while also offer comfort and support. They also help to compile and spread useful information on group-purchasing so that other residents in the same street or same district can also find ways to buy daily necessities.

Challenges, potential and implications of the emerging spontaneous groups

The COVID-19 pandemic brought unprecedented challenges for the government and the society worldwide, driving drastic changes to urban governance, especially at the community level. Due to the party-state governance nature of China, discussions around China's COVID-19 responses have largely focused on the governmental policies and measures. Recognizing the fragmented and decentralized socio-political system in practice, a number of studies have also explored the roles of various actors, especially the local officials and residents, in combatting the pandemic. In their recent study, Du and Tan (2022), p. 1 conclude that “the outbreak enables the government to (re-)build a location-based urban management system with the participation of residents facing the pandemic as an external threat”. However, we argue that such a narrative diminishes the active role and strong initiatives of the public in self-organizing governance (see Song et al., 2020). It also tends to ignore the bottom-up localized responses of citizens and villagers, which were also witnessed in other places in China (Tan et al., 2021). Our examination of the civil society-led community governance in the recent Shanghai outbreak thus makes a timely contribution in understanding the hybrid governance in urban China during the pandemic.

In the previous section we have analyzed the architecture and operation of typical non-state-led self-organizing groups emerging in Shanghai amid the outbreak. These spontaneous and grassroots groups quickly form close social communities that enable self-help and mutual aid among individuals and households. They also act as the intermediary agency between residents and the government (represented by the RC), filling the voids and gaps in the neighborhood level COVID-19 prevention and control. While demonstrating great potential, in practice these spontaneous groups encountered a series of challenges from both inside and outside. Firstly, since community group-buying is spontaneously organized by residents, there lacked supervision at the earlier stage, which allowed the exploitation for price gouging and price frauds, monopolies, and other illegitimate pricing8. Such acts not only harm consumers' rights and interests but also undermine the trust and credibility of similar spontaneous groups. Many group-purchasing leaders (Tuan-Zhang) also quitted their positions due to the heavy workload and huge pressure at the worst stage of the outbreak. Meanwhile, in some neighborhoods, self-organized activities including community group purchases were restricted or even banned by the local governments, citing contagion risks and manpower shortage in supervision. In addition, as the situation gradually improved and as major tech platforms started partnering up with local authorities to ensure the well-functioning of Shanghai's logistics chains9, there is less need and little room for spontaneous groups' group-buying activities.

Nederhand et al. (2016) point out the six key factors of building and maintaining a spontaneous, continuously evolving and self-maintaining self-organization, including a trigger (external conditions) to generate interaction; trustworthy relationship among actors (normally social capital in the community); interactions and exchanges of information; shared and evolving knowledge and information base; key opinion leaders for boundary-spanning; adaptation to existing governance frameworks, such as laws, norms, etc. As discussed above, the spontaneous groups in Shanghai have emerged and developed online communication platform or toolkits for mutual-aid that complement the local governments and administrations' efforts under the COVID-19 outbreak. They have further formed a network with clear work division and spontaneous hierarchy, which built up the trust and enabled communication and interactions among residents. However, the structure of the spontaneous groups is found to be not stable enough to sustain themselves and can be greatly impacted by the change of external conditions. Many groups thus encountered difficulties in adapting to the current community governance framework and transforming into a self-organization, or even self-governance or shared-governance (Zhang et al., 2020).

Although many spontaneous groups were found to suspend their activities gradually, it remains to be seen whether and how they may affect the community governance and further contribute to urban resilience building in Shanghai and beyond. Previous studies have also documented the dynamic interactions among different actors during the COVID-19 lockdown in China, both in urban and rural areas (see Song et al., 2020; Tan et al., 2021). While localized, grassroots responses have also been witnessed in Shanghai, they present varied forms and focuses that revolve around daily necessities supply and mental health care instead of assisting the local authorities in implementing lockdown measures or presenting different voices as opposed to the official narratives. Whilst the purpose of this study is not to provide a comprehensive account of the various forms and endeavors of different community governance led by non-state actors, we argue that more systemic comparative studies are needed to explore the contextualized responses and resilience building to crises like COVID-19 domestically and internationally.

Moreover, self-governance and shared-governance of urban community are based on shared values and collective actions, as well as good communication and cooperation between residents and residents, residents and the outside environment, and residents and the government (Zhang et al., 2020). Therefore, how to unlock the potential of spontaneous groups in catalyzing more profound transformative changes of urban community governance in China, such as empowering grassroots actors and motivating wider public participation in decision-making process, is an important question to be further explored. It is worth noting that even if those spontaneous groups are just temporary responses, their self-organizing activities are valuable experiments for public engagement in urban community affairs and management.

Conclusion

Community-based pandemic prevention and control has been the core strategy for fighting the COVID-19 pandemic in urban China. Effective community governance is thus vitally important. Yet the severe outbreak in Shanghai in early 2022 brought unprecedented challenges for the local governments and the whole society. While scholars have already noted the “re-localization” or “comeback of localism” in urban China by exploring how city governments (re-)built a location-based urban management system during the pandemic (Du and Tan, 2022), our close investigation of the emerging spontaneous groups in Shanghai, as well as their architecture, operations, and collaborations with other key actors (both state and non-state) provide a detailed account of the hyper local dynamics of the civil society. The social sense of community has been built via numerous spontaneous groups that were formed based on common needs and interests, as well as the well-developed information and communication technology. The newly built communities then become a key resource for enabling, facilitating, and implementing more efficient and effective governance. As an integral component of the governance, these emerging communities complement the government in responding to the public health emergency. Whether they can outlast COVID-19 remains to be seen, yet the crucial roles they played as well as the significant influences they brought well demonstrate the value of their existence. Future research, thus, should investigate how to enable, maintain, and further promote the development of grassroots initiatives and spontaneous groups, identify the main challenges and opportunities, and explore pathways for fostering and normalizing various communities for urban community governance in China.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Author contributions

All authors listed have made a substantial, direct, and intellectual contribution to the work and approved it for publication.

Funding

This study was supported by internal funding from the University of Nottingham Ningbo China.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Footnotes

1. ^The Dynamic Zero-COVID policy has been proposed by National Health Commission (NHC) since August 2021 to address the rapid spread of COVID-19 in China. Through regular periodic nucleic acid detection and big data technology, infection cases and close contacts (mi-jie and ci-mi-jie) are identified. The areas with infections are then divided into risk areas where mobility is restricted to reduce the impacts on socioeconomic development of other regions and even the whole country (Liang et al., 2022). The policy has greatly reduced the number of infections and deaths. As of November 12, 2022, China has a total of 270,257 confirmed infections and 5,226 deaths (NHC., 2022), while the cumulative number of infections in the United States is 97,990,681 and the death toll is 1,074,524 (JHU., 2022).

2. ^From 1 March 2022 to 5 May 2022, there were 597,424 confirmed cases of COVID-19 in Shanghai, while during the same period in 2021, there were zero local cases, according to the Shanghai Municipal Health Commission [see https://wsjkw.sh.gov.cn/yqtb/index.html (accessed November 13, 2022)].

3. ^The urban grid management system is responsible for both mundane community affairs (such as welfare provision) and nonregular tasks in public emergency situations (such as carrying out nucleic acid inspections and daily necessity supply amid the COVID-19 outbreak). One urban grid (wang-ge) usually consists of 1000 households and has a grid head (wang-ge-zhang) (normally a member of the Residents' Committees) and grid managers (wang-ge-yuan) (normally voluntary residents) (Xiang, 2021).

4. ^Organic law of the Urban Residents' Committees of the People's Republic of China, Article 2, December 1989.

5. ^As of February 2021, there are more than 900,000 registered CSOs in China (Xinhua., 2022). The development of CSOs in metropolises is far ahead compared to other cities in China. Shanghai has 17367 CSOs by the end of 2021, covering fields of relief for vulnerable groups, education, culture, health, sports, environmental protection, etc. (Gu, 2022).

6. ^On April 30, 2022, Shanghai Government held a press conference on the latest COVID-19 situation, in which the deputy director of the Shanghai Commission of Commerce reported the reopening of 1,164 supermarkets (about 72.4%) and the recovery of e-commerce with the daily order volume of major e-commerce platforms reaching 3.413 million orders, returning to 54.1% of the normal level in Shanghai (Guo, 2022). This demonstrated the severe interruptions of daily shopping in Shanghai during the peak of the outbreak.

7. ^See: https://mp.weixin.qq.com/s/na3bym_Hpwpi4ELg7__Kng (accessed April 16, 2022).

8. ^See: https://www.samr.gov.cn/jjj/gfzxydjcx/202205/t20220522_347188.html (accessed June 3, 2022) about the Shanghai Market Supervision Bureau cracked down on the illegal activities of community group purchase prices.

9. ^Chinese e-commerce giant JD.com, for example, pledged to coordinate the bulk delivery of daily necessities to the city as it attempts to return to normality.

References

Bentley, J. G. (2004). Survival strategies for civil society organizations in China. Int. J. Non-for Profit Law. 6. Available online at: https://www.icnl.org/resources/research/ijnl/survival-strategies-for-civil-society-organizations-in-china

Bhattacharyya, J. (2004). Theorizing community development. Commun. Develop. 34, 5–34. doi: 10.1080/15575330409490110

Bray, D. (2006). Building ‘community': New strategies of governance in urban China. Econ. Soc. 35, 530–549. doi: 10.1080/03085140600960799

Bray, D. (2009). “Building ‘community': New strategies of governance in urban China,” in China's Governmentalities, Routledge. 100–118. doi: 10.4324/9780203873724-10

Cai, Y. (2022). How the Lockdown Is Remaking Shanghai Neighborhoods. Sixth Tone. Available online at: https://www.sixthtone.com/news/1010174/how-the-lockdown-is-remaking-shanghai-neighborhoods (accessed May 25, 2022).

CCCPC and State Council (2017). Opinions of the Central Committee of the Communist Party of China and the State Council on Strengthening and Improving Urban and Rural Community Governance.

Chen, Y., and Qu, L. (2020). Emerging participative approaches for urban regeneration in Chinese megacities. J. Urban Plan. Develop. 146, 4019029. doi: 10.1061/(ASCE)UP.1943-5444.0000550

Du, S., and Tan, H. (2022). Location is back: The influence of COVID-19 on Chinese cities and urban governance. Sustainability. 14, 3347. doi: 10.3390/su14063347

Dynes, R. R. (1970), Organized Behavior in Disaster. Ohio: Disaster Research Center, Ohio State Universit.

Gu, J. (2022). ‘Shanghai Charity Week' Has Been Launched (in Chinese). Liberation Daily. Available online at: https://www.shio.gov.cn/TrueCMS//shxwbgs/ywts/content/e8584a94-6f52-483c-ad7f-4cd01e3250d7.htm (accessed November 12, 2022).

Guo, S., and Yin, L. (2019). “Adaptability Changes in Economic and Social Transformation:Community Governance in Shanghai in the Past 40 Years 9 (in Chinese),” in Urban Governance Study: 40 Years of Urban China Governance, 上海交通大学出版社有限公司. 66.

Guo, Z. (2022). 1,164 Supermarkets Have Reopened in Shanghai (in Chinese). Available online at: https://m.youth.cn/qwtx/xxl/202204/t20220430_13658266.htm (accessed November 12, 2022).

Heberer, T. (2019). ‘Urban Neighbourhood Communities'(shequ) as New Institutions of Urban Governance. Handbook on Urban Development in China: Edward Elgar Publishing. doi: 10.4337/9781786431639.00033

Huang, P., Ma, H., and Liu, Y. (2018). Socio-technical experiments from the bottom-up: The initial stage of solar water heater adoption in a ‘weak'civil society. J. Cleaner Prod. 201, 888–895. doi: 10.1016/j.jclepro.2018.08.087

JHU. (2022). COVID-19 Dashboard. Center for Systems Science and Engineering (CSSE) at Johns Hopkins University (JHU).

Jiang, S. (2009). Learning from Self-Organization among Service Volunteers after the Wenchuan Earthquake–The Case of Ad Hoc Volunteer Organization K388. China Nonprofit Rev. 1, 285–301. doi: 10.1163/187651409X462359

Liang, W., Liu, Mi., Liu, J., Wa, Y., Wu, J., and Liu, X. (2022). The dynamic COVID-zero strategy on prevention and control of COVID-19 in China (in Chinese). Natl. Med. J. China 102, 239–242. doi: 10.3760/cma.j.cn112137-20211205-02710

McMillan, D. W., and Chavis, D. M. (1986). Sense of community: A definition and theory. J. Commun. Psychol. 14, 6–23. doi: 10.1002/1520-6629(198601)14:1<6::AID-JCOP2290140103>3.0.CO;2-I

Nederhand, J., Bekkers, V., and Voorberg, W. (2016). Self-organization and the role of government: How and why does self-organization evolve in the shadow of hierarchy? Public Manage. Rev. 18, 1063–1084. doi: 10.1080/14719037.2015.1066417

NHC. (2022). Latest Situation of COVID-19 as of 24:00 on November 11, 2022. National Health Commission. Available online at: http://www.gov.cn/xinwen/2022-11/12/content_5726374.htm (accessed November 12, 2022).

Petrescu-Prahova, M., and Butts, C. (2005). Emergent Coordination in the World Trade Center Disaster. UC Irvine: Institute for Mathematical Behavioral Sciences. Retrieved from: https://escholarship.org/uc/item/5021t6h7

Qu, D. (2016). The owners' committee in China: A non-owner owned puppet? Tsinghua China L. Rev. 8. Available online at: https://ssrn.com/abstract=2814269

Ren, B., Shou, H., and Dong, L. (2015). “Internet and mobilization in China's urban environmental protests”, in Urban Mobilizations and New Media in Contemporary China, eds. H. Kriesi, L. Dong, and D. Kübler (London: Ashgate Publishing, Ltd.).

Shieh, L., and Friedmann, J. (2008). Restructuring urban governance: Community construction in contemporary China. City. 12, 183–195. doi: 10.1080/13604810802176433

Song, Y., Liu, T., Wang, X., and Guan, T. (2020). Fragmented restrictions, fractured resonances: grassroots responses to Covid-19 in China. Crit. Asian Stud. 52, 494–511. doi: 10.1080/14672715.2020.1834868

Southern Weekend. (2021). PRC Civil Code ‘tests' the Owner's Committee: How to Understand ‘More than Two-thirds Participation'? Available online at: https://static.nfasouthcn.com/content/202106/10/c5390270.html (accessed November 12, 2022).

Tan, X., Song, Y., and Liu, T. (2021). Resilience, vulnerability and adaptability: A qualitative study of COVID-19 lockdown experiences in two Henan villages, China. PLoS ONE. 16, e0247383. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0247383

Wan, X. (2015). Governmentalities in Everyday Practices: The Dynamic of Urban Neighbourhood Governance in China. London, England: Urban Studies, SAGE PublicationsSage UK. doi: 10.1177/0042098015589884

Wang, Y. P., and Murie, A. (2000). Social and spatial implications of housing reform in China. Int. J. Urban Reg. Res. 24, 397–417. doi: 10.1111/1468-2427.00254

Wei, Y., Ye, Z., Cui, M., and Wei, X. (2021). COVID-19 prevention and control in China: grid governance. J. Public Health, 43, 76–81. doi: 10.1093/pubmed/fdaa175

Xiang, B. (2021). The nearby: A scope of seeing. J. Contemp. Chinese Art. 8, 147–165. doi: 10.1386/jcca_00042_1

Xie, L. (2022). “Nature-based Solutions for Transforming sustainable urban development in China” in Green Infrastructure in Chinese Cities, ed. A. Cheshmehzangi (Springer Nature), 469–493.

Xinhua. (2022). China Has Registered More than 900,000 Civil Society Organizations. Available online at: http://www.gov.cn/xinwen/2021-02/09/content_5586274.htm (accessed November 12, 2022).

Zhang, Q., Yung, E. H. K., and Chan, E. H. W. (2018). Towards sustainable neighborhoods: Challenges and opportunities for neighborhood planning in transitional urban China. Sustainability. 10, 406. doi: 10.3390/su10020406

Keywords: community governance, city, spontaneous groups, COVID-19, China

Citation: Xie L and Shao M (2022) The rejuvenation of urban community in China under COVID-19. Front. Sustain. Cities 4:960547. doi: 10.3389/frsc.2022.960547

Received: 03 June 2022; Accepted: 15 November 2022;

Published: 01 December 2022.

Edited by:

Tathagata Chatterji, Xavier University, IndiaReviewed by:

Junaid Ahmad, Peshawar Medical College, PakistanVenus Khim-Sen Liew, Universiti Malaysia Sarawak, Malaysia

Copyright © 2022 Xie and Shao. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Linjun Xie, Linjun-xie@nottingham.edu.cn

Linjun Xie

Linjun Xie Mengqi Shao

Mengqi Shao