Abstract

Background

In preclinical Alzheimer’s disease, it is unclear why some individuals with amyloid pathologic change are asymptomatic (stage 1), whereas others experience subjective cognitive decline (SCD, stage 2). Here, we examined the association of stage 1 vs. stage 2 with structural brain reserve in memory-related brain regions.

Methods

We tested whether the volumes of hippocampal subfields and parahippocampal regions were larger in individuals at stage 1 compared to asymptomatic amyloid-negative older adults (healthy controls, HCs). We also tested whether individuals with stage 2 would show the opposite pattern, namely smaller brain volumes than in amyloid-negative individuals with SCD. Participants with cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) biomarker data and bilateral volumetric MRI data from the observational, multi-centric DZNE-Longitudinal Cognitive Impairment and Dementia Study (DELCODE) study were included. The sample comprised 95 amyloid-negative and 26 amyloid-positive asymptomatic participants as well as 104 amyloid-negative and 47 amyloid-positive individuals with SCD. Volumes were based on high-resolution T2-weighted images and automatic segmentation with manual correction according to a recently established high-resolution segmentation protocol.

Results

In asymptomatic individuals, brain volumes of hippocampal subfields and of the parahippocampal cortex were numerically larger in stage 1 compared to HCs, whereas the opposite was the case in individuals with SCD. MANOVAs with volumes as dependent data and age, sex, years of education, and DELCODE site as covariates showed a significant interaction between diagnosis (asymptomatic versus SCD) and amyloid status (Aß42/40 negative versus positive) for hippocampal subfields. Post hoc paired comparisons taking into account the same covariates showed that dentate gyrus and CA1 volumes in SCD were significantly smaller in amyloid-positive than negative individuals. In contrast, CA1 volumes were significantly (p = 0.014) larger in stage 1 compared with HCs.

Conclusions

These data indicate that HCs and stages 1 and 2 do not correspond to linear brain volume reduction. Instead, stage 1 is associated with larger than expected volumes of hippocampal subfields in the face of amyloid pathology. This indicates a brain reserve mechanism in stage 1 that enables individuals with amyloid pathologic change to be cognitively normal and asymptomatic without subjective cognitive decline.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Alzheimer’s disease is characterized by a long preclinical course of amyloid and related pathologies before cognitive performance declines to the level of mild cognitive impairment (MCI). In this preclinical stage, the experience of progressive subjective cognitive decline (SCD) is considered a symptomatic indicator of stage 2 of the Alzheimer’s continuum, which is preceded by the asymptomatic stage 1 [1,2,3].

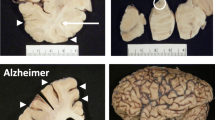

An important question is why some individuals are asymptomatic and therefore fall into stage 1, while others experience symptoms and therefore fall into stage 2. One possibility is that both stages form a continuum of subtle preclinical progression with brain atrophy in which the degree of atrophy in stage 1 is not sufficiently severe to cause symptoms (Fig. 1). Alternatively, individual differences in brain reserve may impact on symptom manifestation in the presence of amyloid (Fig. 1). A commonly reported domain of subjective decline in the context of AD is related to episodic long term memory [1, 2, 4]. According to a continuous model, brain regions early affected in AD and related to memory function and subjectively perceived memory deficits would show evidence of subtle atrophy in stage 1 compared to a status without amyloid (Fig. 1). In stage 2, this atrophy would be more pronounced, causing subjectively experienced memory dysfunction. The alternative is the presence of intact brain reserve in stage 1, which would prevent subjectively experienced memory dysfunction and the absence of sufficient brain reserve at stage 2 (Fig. 1).

Hypothetical volumes of memory regions in amyloid-negative (A−) asymptomatic healthy controls, A− subjective cognitive decline (SCDs), stages 1 and 2. According to a continuum model, volumes should be gradually smaller from A− asymptomatic to 2. According to a brain reserve model, stage 1 should have higher volumes than A− asymptomatic (“higher than expected”), while stage 2 should show the expected decrease. The A− SCD group serves as a control that any volume differences between stages 1 and 2 are not solely attributable to the presence of memory complaints

In the recent Reserve and Resilience working group research framework, brain reserve has been defined as better than expected brain integrity related to cognitive function in the face of a pathology [5]. According to this possibility, individuals in stage 1 may show larger volumes of memory-related brain regions compared to individuals without amyloid as an indicator of higher brain reserve. In stage 2, indicated by SCD, on the other hand, the reverse pattern could be expected and interpreted as an indicator of lower brain reserve (Fig. 1). In this scenario, the cross-sectional and longitudinal impact of amyloid pathology would depend on the presence of brain reserve. Individuals with low brain reserve would remain in stage 1 for a short duration and progress rapidly to stage 2, while those with high brain reserve would remain longer in stage 1 and progress slowly to stage 2.

The functional anatomical hallmark of episodic memory is the medial temporal lobe with the hippocampal formation and parahippocampal region [6,7,8]. In order to detect subtle atrophy patterns in these regions, it is worthwhile to assess the volumes of subfields in the hippocampal formation and subregions in the parahippocampal region (i.e., [8]). Recently, segmentation algorithms to detect the anatomical boundaries of subfields and subregions on MRI have considerably improved [9,10,11].

In this study, we measured the volumes of the hippocampal formation subfields, notably the dentate gyrus (DG), CA1, CA2/CA3, and subiculum according to a recently developed segmentation protocol for high-resolution T2 images [9]. We also measured volumes of parahippocampal regions, notably the entorhinal cortex (ErC), the perirhinal cortex with Brodmann areas 35 (transentorhinal cortex) and 36, and the parahippocampal cortex (PhC). We tested whether in asymptomatic individuals and those with SCD who were either amyloid-negative (A−) or amyloid-positive (A+), the volume pattern of the subfields and subregions was compatible with a continuum interpretation (amyloid negative > stage 1 > stage 2) or a brain reserve interpretation (stage 1 > amyloid negative; stage 1 > stage 2; interaction between amyloid status and the presence/absence of memory complaints). To that end, we utilized data from the multicentric DELCODE study of the German Center for Neurodegenerative Diseases.

We included the A− SCD group in the test of the continuum versus the brain reserve model, in order to account for the possibility that all patients with SCD have smaller hippocampi, irrespective of their amyloid status, when compared to asymptomatic individuals (resulting in a main effect of memory complaints). Such a possibility would argue against a role of amyloid pathology in explaining differences between stages 1 and 2. Therefore, the interaction of clinical stage (1 and 2) and amyloid status (A− and A+) with respect to brain volume would be a critical test of a brain reserve hypothesis (Fig. 1).

Methods

The DELCODE study (for details, see [12]) is an observational longitudinal memory clinic-based multicenter (10 sites) study of the German Center for Neurodegenerative Diseases (DZNE) in Germany. It comprises the clinical stages of Alzheimer’s disease from stage 1 (asymptomatic and amyloid-positive) to stage 4 (early dementia) as well as amyloid-negative cognitive unimpaired individuals. Asymptomatic individuals were defined by an age-, sex-, and education-adjusted performance within − 1.5 standard deviations (SD) on all tests of the CERAD (consortium to establish a registry of Alzheimer’s disease test battery) cognitive test battery. SCD was defined by the presence of subjectively reported decline in cognitive functioning and a test performance above − 1.5 SD below the age-, sex-, and education-adjusted normal performance on all subtests of the CERAD [2]. Participants with SCD were referrals to the memory clinic including self-referrals while the control group was recruited by standardized public advertisement.

Additional inclusion criteria for both groups were age ≥ 60 years, fluent German language skills, capacity to provide informed consent, and presence of a study partner. For exclusion criteria, see [12].

The annual neuropsychological testing in DELCODE included the PACC5 [13]. The PACC5 z-score was calculated as the mean performance z-score across the Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE), a 30-item composite screening test, the Wechsler Memory Scale Logical Memory Delayed Recall, a test of delayed (30 min) story recall, the Digit-Symbol Coding Test (DSCT; 0–93), a test of memory, executive function and processing speed, the Free and Cued Selective Reminding Test–Free Total Recall (FCSRT96; 0–96), a test of free and cued recall of newly learned associations, and the Category Fluency Test, a test of semantic memory and executive function [14,15,16,17]. The z-scores for the PACC5 in our analysis were derived using the mean and standard deviation of healthy controls and participants with SCD as well as relatives of patients with dementia in the entire DELCODE study.

All local institutional review boards and ethical committees approved the study protocol. All participants gave written informed consent before inclusion in the study. DELCODE is registered at the German Clinical Trials Register (DRKS00007966) (04/May/2015). Data handling and quality control are reported in [12].

Sample

T1 and T2 MRI datasets were obtained from 916 participants at baseline. Of these, 433 participants had also CSF data available, which was used to define amyloid positivity (see below). The MRI data underwent automatic segmentation of hippocampal subfields and parahippocampal region according to the protocol outlined below. After manual inspection by an experienced rater (see below) 272 participants had hippocampal segmentations that passed quality assessment for both hemispheres. This final segmentation sample comprised 95 amyloid-negative (A−) asymptomatic individuals, 26 amyloid-positive (A+) asymptomatic individuals, 104 A− SCD, and 47 A+ SCD. The remaining participants of the segmentation sample had MCI and early dementia and were not considered for the current analysis.

CSF Alzheimer’s disease biomarker assessment

CSF Alzheimer’s disease biomarkers were determined centrally at the Bonn site using commercially available kits according to vendor specifications (V-PLEX Aβ Peptide Panel 1 (6E10) Kit, K15200E and V-PLEX Human Total-tau Kit, K151LAE (Mesoscale Diagnostics LLC, Rockville, USA), and Innotest PhosphoTau (181P), 81581, Fujirebio Germany GmbH, Hannover, Germany) (also see [12]). Cut-offs were calculated from the DELCODE dataset by Gaussian mixture modeling using the R package flexmix (version 2.3-15). The following cut-offs were determined: Aß42 ≤ 638.7 pg/ml, Aß42/Aß40 ≤ 0.08 pg/ml, total Tau > 510.9 pg/ml, phospho-tau ≥ 73.65 pg/ml, and Aß42/phospho-tau < 9.68 pg/ml. The cut-off of the Aß42/Aß40 ratio was used to define amyloid positivity.

MRI acquisition

MRI data were acquired at nine DELCODE scanning sites, all equipped with Siemens scanners (3 TIM Trio systems, 4 Verio systems, one Skyra, and one Prisma system). For the current report, T1-weighted (3D GRAPPA PAT 2, 1 mm3 isotropic, 256 × 256px, 192 slices, sagittal, ~5 min, TR 2500 ms, TE 4.33 ms, TI 110 ms, FA 7°) and T2-weighted (optimized for MTL volumetry, 0.5 × 0.5 × 1.5 mm3, 384 × 384px, 64 slices, orthogonal to the hippocampal long axis, ~12 min, TR 3500 ms, TE 353 ms) images were used. Standard operating procedures, quality assurance, and assessment were provided and supervised by the DZNE imaging network (iNET, Magdeburg) as described in [12].

Volumetric analysis

Automated segmentation of hippocampal and parahippocampal subregions

Automated segmentation of hippocampal subfields (ASHS) was implemented in the entire DELCODE cohort using the Penn ABC-3T ASHS Atlas for T2-weighted MRI [9, 18, 19]. Using this atlas, hippocampal subfields (subiculum, dentate gyrus, Cornu Ammonis 1, 2, and 3, hippocampal tail) and parahippocampal regions (entorhinal cortex, Brodmann areas 35 and 36, parahippocampal cortex) were segmented in correspondence with the manual segmentation protocol by Berron et al. [9].

Each created segmentation mask underwent thorough quality assurance by an experienced rater. Quality ratings were performed separately for each hemisphere and for hippocampal and parahippocampal regions. In the present study, only participants whose segmentation masks passed the quality assurance for both hippocampal and parahippocampal regions in both hemispheres were included.

The quality assurance routine first included a visual inspection of all segmentation masks on five coronal and two sagittal snapshots. If there were no indications of segmentation errors, the respective mask was included for analyses. If it became apparent that segmentation failed, the respective segmentation mask was excluded from analyses. If the snapshots showed indications of possible segmentation errors, the respective segmentation mask was inspected in its entire three-dimensional extent. Here, any segmentation error that was visible on more than two consecutive slices on T2w MRI (i.e., extending more than 3 mm longitudinally) led to manual editing or exclusion of the segmentation mask. Errors affecting the outer boundaries of the segmented structures were edited in accordance with the manual segmentation rules by Berron et al. [9]. Errors that affected internal boundaries between subregions were not edited and led to exclusion of the respective segmentation mask. The rater was blinded to the diagnosis and amyloid status of the participants.

Total intracranial volume

Brain reserve may manifest already early in life [20]. While we sought to identify medial temporal lobe brain reserve, early-life manifestation of such reserve may be associated with widespread brain-effects, depending on the connectivity of the medial temporal region, and this may therefore affect total intracranial volume (TIV). Using TIV as a covariate would therefore weaken the ability to detect brain reserve enacted early in life. Therefore, we did not include TIV as a covariate in our analyses.

Statistical analysis

We conducted a multivariate ANOVA (MANOVA) with segmentation volumes as dependent variables for regions of the hippocampal formation (four regions: CA1, CA3/CA2, DG, subiculum) and another one for parahippocampal regions (four regions: ErC, Brodmann areas 35 and 36, PhC) to assess the effect of diagnosis (asymptomatic versus SCD) and amyloid status (Aß42/40 ratio positive or negative), with age, sex, years of education, and site as covariates. Cook’s distances were used to detect outliers (> 0.6).

Paired comparisons were performed as post hoc paired comparisons on estimated marginal means (taking into account the same covariates) with Fisher’s LSD correction. These comparisons were limited to pair-wise comparisons of amyloid status within diagnostic groups.

An independent sample t-test was conducted to make two comparisons of four hippocampal subfields (CA1, CA2/3, DG, and subiculum): (1) between A+ asymptomatic and A+ SCD and (2) A− asymptomatic and A+ SCD individuals.

Results

The sample characteristics are provided in Table 1. Volumes of hippocampal subfields and parahippocampal regions are reported in Tables 2 and 3, respectively. Planned, independent-sample t-tests showed that amyloid-positive (A+) individuals who were asymptomatic (stage 1) or had SCD (stage 2) in our sample did not differ with respect to years of education (p = 0.734), CSF total tau levels (p = 0.078), Aß42/40 levels (p = 0.257), MMSE scores (p = 0.947), or their PACC5 scores (p = 0.414). A+ SCD patients had significantly higher age (p = 0.023) and CSF phospho-tau levels (p = 0.03) than A+ asymptomatic individuals. Statistical comparisons between asymptomatic A− and SCD A− were not performed.

Comparison of volumes between groups

In a MANOVA for the hippocampal formation, there was no main effect of diagnosis (F(4261) = 0.759; p = 0.559) or amyloid status (F(4261) = 1.289; p = 0.275) but a significant interaction between diagnosis and amyloid status (F(4261) = 3.144; p = 0.015).

Tests of between subject effects were significant for the interaction between diagnosis and amyloid status for the DG (p = 0.004), CA1 (p < 0.001), CA2/CA3 (p = 0.003), and the subiculum (p = 0.027). Analysis of Cook’s distances did not reveal any outliers (all values below 0.6). Post hoc pair-wise comparisons of estimated marginal means in the MANOVA (i.e., adjusted for the same covariates as in the MANOVA; Fisher’s LSD correction) showed significantly larger volumes in A+ than A− asymptomatic individuals for CA1 (p = 0.014) (Fig. 2) and CA2/CA3 (p = 0.047) and nonsignificant differences for DG (p = 0.175) and subiculum (p = 0.293). In SCD, lower volumes in A+ than in A− individuals were significant for DG (p = 0.004), CA1 (p = 0.025) (Fig. 2), CA2/CA3 (p = 0.026), and subiculum (p = 0.028).

Bilateral volumes of the CA1 subfield (in mm3) in asymptomatic individuals and those with SCD. Aß42/40 positive asymptomatic individuals (stage 1) have larger CA1 subfields (p = 0.014) than asymptomatic and Aß42/40 neg. For SCDs, those that are amyloid-positive (stage 2) have smaller CA1 volumes than those that are amyloid-negative. Stage 1 individuals have larger CA1 volumes than stage 2 individuals (p < 0.001). Box and whisker plots show median (thick horizontal lines), minimum and maximum values (lower and upper end of whiskers), and outliers (circle, star). Whiskers below each box show the first quartile range and those above the fourth quartile range of data

We conducted an independent sample t-test to make two comparisons of four hippocampal subfields (CA1, CA2/3, DG, and subiculum): (1) between A+ asymptomatic and A+ SCD and (2) A− asymptomatic and A+ SCD. Results revealed that A+ asymptomatic individuals had larger CA1 (p < 0.001), CA2/CA3 (p = 0.006), DG (p = 0.007), and subiculum (p = 0.004) volumes in the first comparison. Although A+ SCD individuals showed smaller subfields than A− asymptomatic individuals in the second comparison, this did not reach the significance level for CA1 (p = 0.168), CA2/3 (p = 0.282), and DG (p = 0.072) except subiculum (p = 0.008) (see Fig. 2).

For parahippocampal regions, the main effect of diagnosis was not significant (F(4260)=2.278; p = 0.661), the main effect of amyloid status was not significant (F(4260)=3.376; p = 0.845), and their interaction was not significant (F(4260)=2.111; p = 0.623). Test of between subject effects and post hoc pair-wise comparisons were not further considered given the lack of significant main-effects and interactions.

Discussion

We found an interaction between hippocampal subfield volumes and amyloid status in asymptomatic individuals and SCDs (Fig. 2). This interaction is in agreement with the hypothesis that stronger brain reserve, as indicated by brain volumes contributes to distinguishing the stage 1 from stage 2 of the Alzheimer’s continuum. The brain reserve interpretation is supported by the larger CA1 subfield (p = 0.014) and larger CA2/CA3 subfields (p = 0.047) in asymptomatic A+ subjects in a post hoc pair-wise comparison with asymptomatic A− participants (Fig. 2). These findings indicate a higher than expected brain integrity as expressed by a larger CA1 and CA2/CA3 volumes in the presence of amyloid pathology in stage 1 individuals, which is in agreement with the recent Reserve and Resilience working group framework definitions for brain reserve [5].

We found that the interaction between amyloid status and clinical status was particularly strong in the subfields DG, CA1, CA2/CA3, and subiculum, and these subfields were smaller in A+ and A− SCD. Memory processing in the subfields of the hippocampal formation and parahippocampal subregions is organized along designated circuits. The DG supports “pattern separation” of similar events, while CA3 and CA1 enable pattern completion and associative learning, respectively. CA1 also allows orchestrated cortical reinstatement of mnemonic information and novelty detection [21,22,23,24]. The subiculum, in turn, is a major output structure of the hippocampus with a widespread connectivity including other regions of the episodic memory network, such as the retrosplenial region [25, 26]. Therefore, in this scheme, our findings suggest that particularly aspects related to pattern separation, novelty processing, and associative learning should contribute to brain reserve in stage 1. In contrast, the unitization of information and familiarity-based recognition seems to involve the adjacent perirhinal cortex [27,28,29,30]. Perirhinal cortex and adjacent regions (the entorhinal cortex) did not show a significant interaction between amyloid status and clinical stage, suggesting that unitization and familiarity-recognition may not contribute to brain reserve in stage 1.

While the A+ SCDs had numerically smaller volumes than the asymptomatic A− group (Table 2) in all subfields, this difference was only significant in the subiculum. These results suggest that stage 2 is associated with only a subtle atrophy when compared to amyloid-negative older adults without memory complaints. One possible interpretation of these results is that patients with A+ SCD are those individuals who were initially the asymptomatic A− group and developed memory complaints under amyloid pathology through a combination of subtle atrophy (significant in the subiculum) and synaptic dysfunction associated with amyloid oligomers. To what extent the atrophy in the subiculum may play a specific role in contributing to memory complaints in stage 2 remains to be determined and replicated.

Years of education was not different between asymptomatic A+ and A− or between asymptomatic A+ and SCD A+. Hence, brain reserve in stage 1 does not appear to be related to higher levels of education. The neurobiological underpinning of this reserve remains to be determined. Candidate mechanisms may include polygenic factors [31]. There is also the possibility that stage 1 and stage 2 are distinguished by fewer ApoE4 carriers in stage 1 (Table 1). However, our study was not sufficiently powered to assess a three-way interaction between amyloid status, clinical stage, and ApoE4 status.

This study has a number of strengths. We recruited stage 2 in a health care-based approach and therefore our data directly speak to brain reserve in cognitively normal individuals who do not seek medical advice due to memory complaints. We used a new and accurate segmentation protocol that allows accurate segmentation of hippocampal subfields and parahippocampal regions. Finally, we performed a stringent QA of the segmentation results.

Limitations

There are also a short-comings. The sample size was small particularly for the stage 1 individuals and therefore our findings need replication. Furthermore, we did not have a sufficient sample size to stratify according to ApoE4 status.

Conclusion

We provide first evidence that large volumes of hippocampal subfields, particularly CA1, could present a brain reserve mechanism that allows individuals with amyloid-pathologic change to be cognitively normal without experiencing subjective cognitive decline. This effect is not predicted by the level of education. While these findings require replication, they have implications for preclinical AD trials and disease-modifying treatments in preclinical individuals.

Availability of data and materials

The data, which support this study, are not publically available but may be provided upon reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- A+:

-

Amyloid-positive

- A−:

-

Amyloid-negative

- AD:

-

Alzheimer’s disease

- ASHS:

-

Automatic segmentation of hippocampal subfields

- CA:

-

Cornu Ammonis

- CSF:

-

Cerebrospinal fluid

- DELCODE:

-

DZNE-Longitudinal Cognitive Impairment and Dementia Study

- DG:

-

Dentate gyrus

- DSCT:

-

Digit-Symbol Coding Test

- DSI:

-

Dice similarity index

- DZNE:

-

German Center for Neurodegenerative Diseases

- FCSRT:

-

Free and Cued Selective Reminding Test

- HCs:

-

Healthy controls

- ICC:

-

Intraclass correlation coefficients

- MCI:

-

Mild cognitive impairment

- MMSE:

-

Mini-Mental State Examination

- MRI:

-

Magnetic resonance imaging

- PhC:

-

Parahippocampal cortex

- SCD:

-

Subjective cognitive decline

- SD:

-

Standard deviation

- TIV:

-

Total intracranial volume

- QA:

-

Quality assessment

References

Jessen F, Amariglio RE, Buckley RF, et al. The characterisation of subjective cognitive decline. Lancet Neurol. 2020;19:271–8.

Jessen F, Amariglio RE, van Boxtel M, et al. A conceptual framework for research on subjective cognitive decline in preclinical Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimers Dement. 2014;10:844–52.

Jack CR Jr, Bennett DA, Blennow K, et al. NIA-AA Research Framework: toward a biological definition of Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimers Dement. 2018;14:535–62.

Tulving E. Episodic memory: from mind to brain. Annu Rev Psychol. 2002;53:1–25.

Reserve and Resilience Workgroup. Framework for terms used in research of reserve and resilience. https://reserveandresilience.com/framework/ Accessed 12 Oct 2022.

Düzel E, Yonelinas AP, Mangun GR, Heinze H-J, Tulving E. Event-related brain potential correlates of two states of conscious awareness in memory. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 1997;94:5973–8.

Düzel E, Vargha-Khadem F, Heinze H-J, Mishkin M. Brain activity evidence for recognition without recollection after early hippocampal damage. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2001;98:8101–6.

Grande X, Berron D, Maass A, Bainbridge WA, Duzel E. Content-specific vulnerability of recent episodic memories in Alzheimer’s disease. Neuropsychologia. 2021;160:107976.

Berron D, Vieweg P, Hochkeppler A, et al. A protocol for manual segmentation of medial temporal lobe subregions in 7 Tesla MRI. Neuroimage Clin. 2017;15:466–82.

de Flores R, Berron D, Ding SL, et al. Characterization of hippocampal subfields using ex vivo MRI and histology data: Lessons for in vivo segmentation. Hippocampus. 2020;30:545–64.

Yushkevich PA, Munoz Lopez M, de Onzono I, Martin MM, et al. Three-dimensional mapping of neurofibrillary tangle burden in the human medial temporal lobe. Brain. 2021;144:2784–97.

Jessen F, Spottke A, Boecker H, et al. Design and first baseline data of the DZNE multicenter observational study on predementia Alzheimer’s disease (DELCODE). Alzheimers Res Ther. 2018;10:15.

Papp KV, Rentz DM, Orlovsky I, Sperling RA, Mormino EC. Optimizing the preclinical Alzheimer’s cognitive composite with semantic processing: The PACC5. Alzheimers Dement (N Y). 2017;3:668–77.

Folstein M. Mini-mental and son. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 1998;13:290–4.

Wechsler D, Stone CP. Wechsler Memory Scale-revised. San Antonio: Psychological Corporation; 1987.

Wechsler D. WAIS-R Manual: Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale-Revised. San Antonio: Psychological Corporation; 1981.

Grober E, Hall C, Sanders AE, Lipton RB. Free and cued selective reminding distinguishes Alzheimer’s disease from vascular dementia. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2008;56:944–6.

Yushkevich PA, Pluta JB, Wang H, et al. Automated volumetry and regional thickness analysis of hippocampal subfields and medial temporal cortical structures in mild cognitive impairment. Hum Brain Mapp. 2015;36:258–87.

Xie L, Wisse LEM, Wang J, et al. Deep label fusion: A generalizable hybrid multi-atlas and deep convolutional neural network for medical image segmentation. Med Image Anal. 2023;83:102683. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.media.2022.102683.

Stern Y, Barnes CA, Grady C, Jones RN, Raz N. Brain reserve, cognitive reserve, compensation, and maintenance: operationalization, validity, and mechanisms of cognitive resilience. Neurobiol Aging. 2019;83:124–9.

McClelland JL, Goddard NH. Considerations arising from a complementary learning systems perspective on hippocampus and neocortex. Hippocampus. 1996;6:654–65.

Kaifosh P, Losonczy A. Mnemonic functions for nonlinear dendritic integration in hippocampal pyramidal circuits. Neuron. 2016;90:622–34.

Kumaran D, McClelland JL. Generalization through the recurrent interaction of episodic memories: a model of the hippocampal system. Psychol Rev. 2012;119:573–616.

Koster R, Chadwick MJ, Chen Y, et al. Big-loop recurrence within the hippocampal system supports integration of information across episodes. Neuron. 2018;99:1342–54 e1346.

Maass A, Berron D, Harrison TM, et al. Alzheimer’s pathology targets distinct memory networks in the ageing brain. Brain. 2019;142:2492–509.

Berron D, van Westen D, Ossenkoppele R, Strandberg O, Hansson O. Medial temporal lobe connectivity and its associations with cognition in early Alzheimer’s disease. Brain. 2020;143:1233–48.

Fiorilli J, Bos JJ, Grande X, Lim J, Duzel E, Pennartz CMA. Reconciling the object and spatial processing views of the perirhinal cortex through task-relevant unitization. Hippocampus. 2021;31:737–55.

Staresina BP, Davachi L. Object unitization and associative memory formation are supported by distinct brain regions. J Neurosci. 2010;30:9890–7.

Diana RA, Yonelinas AP, Ranganath C. Imaging recollection and familiarity in the medial temporal lobe: a three-component model. Trends Cogn Sci. 2007;11:379–86.

Bowles B, Crupi C, Mirsattari SM, et al. Impaired familiarity with preserved recollection after anterior temporal-lobe resection that spares the hippocampus. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104:16382–7.

de Rojas I, Moreno-Grau S, Tesi N, et al. Common variants in Alzheimer’s disease and risk stratification by polygenic risk scores. Nat Commun. 2021;12:3417.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL. The study was funded by the German Center for Neurodegenerative Diseases (Deutsches Zentrum für Neurodegenerative Erkrankungen [DZNE]) and funded by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG, German Research Foundation) – Project-ID 42589994. ZY and FD have received research support from the Turkish Neurological Society.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

ZY and FD conducted imaging and data analysis. DB supervised imaging analysis and automated segmentation. HB performed quality assurance on the automated segmentation outcomes. ZY and ED interpreted the data and wrote the main manuscript. ED led the design of the study, supervised the study and data collection at the Magdeburg study site, conducted statistical analysis and reviewed. FJ and HG reviewed and provided critical feedback on the manuscript. BHS, ST, ME, GZ, HS, WG, LD, OP, SDF, LSS, JP, EJS, AS, KF, JW, DM, KB, DJ, RP, BSR, IK, CL, MHM, AS, NR, MH, FB, MW, SR, AR, PD, SH, KS, LK, SW, RY, MS, MB were involved in the study design, data collection, and supervision of data collection teams at their respective study sites. All authors reviewed and approved the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

All local institutional review boards and ethical committees approved the study protocol. All participants gave written informed consent before inclusion in the study. DELCODE is registered at the German Clinical Trials Register (DRKS00007966), (04/May/2015).

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Yildirim, Z., Delen, F., Berron, D. et al. Brain reserve contributes to distinguishing preclinical Alzheimer’s stages 1 and 2. Alz Res Therapy 15, 43 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13195-023-01187-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13195-023-01187-9