Abstract

Background

A low amount and extent of Aβ deposition at early stages of Alzheimer’s disease (AD) may limit the use of previously developed pathology-proven composite SUVR cutoffs. This study aims to characterize the population with earliest abnormal Aβ accumulation using 18F-florbetaben PET. Quantitative thresholds for the early (SUVRearly) and established (SUVRestab) Aβ deposition were developed, and the topography of early Aβ deposition was assessed. Subsequently, Aβ accumulation over time, progression from mild cognitive impairment (MCI) to AD dementia, and tau deposition were assessed in subjects with early and established Aβ deposition.

Methods

The study population consisted of 686 subjects (n = 287 (cognitively normal healthy controls), n = 166 (subjects with subjective cognitive decline (SCD)), n = 129 (subjects with MCI), and n = 101 (subjects with AD dementia)). Three categories in the Aβ-deposition continuum were defined based on the developed SUVR cutoffs: Aβ-negative subjects, subjects with early Aβ deposition (“gray zone”), and subjects with established Aβ pathology.

Results

SUVR using the whole cerebellum as the reference region and centiloid (CL) cutoffs for early and established amyloid pathology were 1.10 (13.5 CL) and 1.24 (35.7 CL), respectively. Cingulate cortices and precuneus, frontal, and inferior lateral temporal cortices were the regions showing the initial pathological tracer retention. Subjects in the “gray zone” or with established Aβ pathology accumulated more amyloid over time than Aβ-negative subjects. After a 4-year clinical follow-up, none of the Aβ-negative or the gray zone subjects progressed to AD dementia while 91% of the MCI subjects with established Aβ pathology progressed. Tau deposition was infrequent in those subjects without established Aβ pathology.

Conclusions

This study supports the utility of using two cutoffs for amyloid PET abnormality defining a “gray zone”: a lower cutoff of 13.5 CL indicating emerging Aβ pathology and a higher cutoff of 35.7 CL where amyloid burden levels correspond to established neuropathology findings. These cutoffs define a subset of subjects characterized by pre-AD dementia levels of amyloid burden that precede other biomarkers such as tau deposition or clinical symptoms and accelerated amyloid accumulation. The determination of different amyloid loads, particularly low amyloid levels, is useful in determining who will eventually progress to dementia. Quantitation of amyloid provides a sensitive measure in these low-load cases and may help to identify a group of subjects most likely to benefit from intervention.

Trial registration

Data used in this manuscript belong to clinical trials registered in ClinicalTrials.gov (NCT00928304, NCT00750282, NCT01138111, NCT02854033) and EudraCT (2014-000798-38).

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Extracellular amyloid-beta (Aβ) aggregates are a key pathologic hallmark of Alzheimer’s disease (AD) [1]. Aggregation of Aβ is a slow and protracted process which may extend for more than two decades before the onset of clinical symptoms [2]. The lack of success of anti-Aβ therapeutic clinical trials in reducing the cognitive decline in AD [3, 4] has encouraged investigators to start intervention at the earliest possible phase when abnormalities in amyloid biomarkers are detectable even at the asymptomatic stage [5,6,7,8].

Amyloid positron emission tomography (PET) with 18F-florbetaben is an established biomarker of Aβ deposition [9]. Visual assessment of 18F-florbetaben PET is used in the clinical setting to estimate Aβ neuritic plaque density and to classify scans as Aβ-positive or Aβ-negative. Visual assessment was validated against histopathological confirmation of the presence of Aβ deposition [9, 10], but it is dichotomous and may lack sensitivity to assess longitudinal changes. In the research setting, a quantitative approach using composite standardized uptake value ratios (SUVRs) calculated from selected cerebral cortical areas is currently being used as a screening tool in clinical trials and is able to detect Aβ changes either in clinical trials after an anti-Aβ drug is administered or in longitudinal observational studies [11]. 18F-Florbetaben PET SUVR abnormality cutoffs have also been developed to accurately categorize scans [12]. An SUVR abnormality cutoff of 1.478 in a global cortical composite region relative to the cerebellar cortex was developed using histopathological confirmation as the standard of truth providing excellent sensitivity (89.4%) and specificity (92.3%) to detect established Aβ pathology [9]. Other groups have developed other SUVR abnormality cutoffs for 18F-florbetaben PET ranging from 1.38 to 1.45 using different populations, analytical methods, and standards of truth [10, 12,13,14,15,16,17,18]. These SUVR cutoffs, however, were developed with the aim of discriminating between subjects with established Aβ pathology (e.g., AD) and other populations (e.g., cognitively normal elderly subjects). Therefore, these global SUVR cutoffs are not optimal to detect the earliest abnormal pathophysiological accumulation of amyloid load and do not provide topographical information. In addition, several studies have shown that measures of Aβ deposition below a threshold of established Aβ pathology carry critical information on initial pathological brain changes and may indicate appropriate time periods for interventions [19]. Moreover, the regional evolution of Aβ load may enable earlier identification of subjects in the AD pathologic continuum and may overcome dichotomous measures [20]. Regional information has shown to be relevant in staging Aβ pathology [21,22,23], tracking disease progression, and assessing the risk of cognitive decline [23,24,25].

The aim of this study was to characterize the population with the earliest abnormal pathophysiological Aβ accumulation using 18F-florbetaben PET and to identify those subjects that will likely accumulate Aβ over time. To this end, a sample of young cognitively normal subjects (20–40 years) scanned with 18F-florbetaben PET was used to develop regional SUVR cutoffs to detect early Aβ accumulation. Subsequently, the topography of abnormal Aβ accumulation, Aβ accumulation over time, progression to AD dementia, and tau deposition were assessed in older cognitively impaired or cognitively unimpaired individuals with early and established Aβ accumulation.

Materials and methods

Participants

The study population consisted of 686 subjects who underwent at least one 18F-florbetaben PET and T1-weighted MRI scans in established research cohort studies summarized in Table 1. The clinical diagnosis of the study participants included young and cognitively normal healthy controls (20–40 years) (yHC, n = 65), elderly healthy controls (eHC, n = 223), subjects with subjective cognitive decline (SCD, n = 168), subjects with mild cognitive impairment (MCI, n = 129), and subjects with AD dementia (n = 101). The sample of yHC (n = 65) (dataset #1) was used to develop an SUVR cutoff for early Aβ accumulation. A sample of eHC (n = 66) and AD (n = 73) subjects (dataset #2) was used to develop an SUVR cutoff for established Aβ pathology using ROC analysis. A subset of participants with SCD and MCI (n = 212) (datasets #3 and #4) underwent two or three 18F-florbetaben PET scans to assess Aβ deposition over time. A subset of MCI subjects (datasets #4) that underwent three 18F-florbetaben PET scans at baseline (n = 44), 1 year (n = 40), and 2 years (n = 35) and a 4-year clinical follow-up was used to assess conversion to AD dementia in addition to Aβ deposition over time. Another subset of participants (dataset #5) (n = 157 (eHC), n = 85 (MCI), n = 28 (AD)) underwent a 18F-flortaucipir PET in addition to the 18F-florbetaben PET to assess the association between Aβ and tau deposition. Subjects from the ADNI study were not assessed visually. The demographic characteristics of the samples and image acquisition methods are summarized in Table 1 and supplemental material 1.

Image analysis

18F-Florbetaben acquisition and image processing

Details on the PET image acquisition and reconstruction are provided in the respective original publication of the studies used (Table 1). In short, all subjects underwent a 20-min PET scan (4 × 5 min dynamic frames) starting at least 90 min after intravenous injection of 300 MBq ± 20% of 18F-florbetaben followed by a 10-mL saline flush. PET scans were reconstructed using Ordered Subsets Expectation Maximization (OSEM) algorithm using 4 iterations and 16 subsets (zoom = 2) or comparable reconstruction. Corrections were applied for attenuation, scatter, randoms, and dead time. Three-dimensional volumetric T1-weighted brain magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) data was also collected. Then, a Gaussian smoothing kernel was applied to all the scans to bring the 18F-florbetaben PET images from different scanner models to a uniform 8 × 8 × 8 mm spatial resolution. The Gaussian smoothing kernel for each scanner was determined using previously acquired Hoffman brain phantoms [27]. Image analysis of 18F-florbetaben PET scans was conducted using SPM8 (https://www.fil.ion.ucl.ac.uk/spm/software/spm8/). Motion correction was performed on each PET frame, and an average PET image was generated. Then, the average PET scan was co-registered to its associated T1-weighted MRI scan. Subsequently, the MRI image was segmented into gray matter, white matter, and cerebrospinal fluid, and spatially normalized to the standard MNI (Montreal Neurological Institute) space. The normalization transformation was applied to the co-registered PET scans and gray matter probability maps.

MRI-derived ROIs

Regions of interest (ROIs) were defined as the intersection between the standard Automated Anatomic Labeling (AAL) atlas [28] and the normalized gray matter segmentation map thresholded at a probability level of 0.2. ROIs included the cerebellar gray matter and frontal (orbitofrontal and prefrontal), lateral temporal (inferior and superior), occipital, parietal, precuneus, anterior cingulate, posterior cingulate, striatum, amygdala, and thalamus. Mean radioactivity values were obtained from each ROI without correction for partial volume effects applied to the PET data. SUVR was calculated as the ratio of the activity in the target ROI to the activity in the reference region ROI (cerebellar gray matter). A composite SUVR was calculated by unweighted averaging the SUVR of the 6 cortical regions (frontal, lateral temporal, occipital, parietal, anterior, and posterior cingulate cortices) [29].

Calibration to centiloid (CL) scale

Given that SUVR values may depend on the tracer used and analytical methods, all the analysis of this paper were provided in CL scale to make the cutoffs useful to other groups or when using other amyloid tracers. Centiloid (CL) values were calculated for each 18F-florbetaben PET using the method described by Klunk et al. [30]. ROIs downloaded from the Global Alzheimer’s Association Interactive Network (GAAIN) website (http://www.gaain.org) for the cerebral cortex and the whole cerebellum were applied to the normalized 18F-florbetaben PET. Cortical SUVR was calculated as the ratio of the activity in the cortex to the activity in the reference region ROI (whole cerebellum). Finally, the CL values were calculated (CL = 153.4 ⋅ SUVR − 154.9) [31]. The in-house implementation of the standard CL analysis was validated using data freely accessible at the GAAIN website (http://www.gaain.org). SUVRs and CL values from the validation dataset were compared by means of linear correlation to those reported by Klunk et al. [30] (SUVRKlunk, CLKlunk). The in-house implementation of standard CL analysis passed all the validation criteria described by Klunk et al. [30] being SUVR = 1.01 SUVRKlunk − 0.01 (R2 = 0.998) and CL = 1.00 CLKlunk + 0.00 (R2 = 1.00) the regression lines when the whole cerebellum was used as the reference region.

18F-Flortaucipir (18F-AV1451) acquisition and image processing

Details on the PET image acquisition and reconstruction are provided in ADNI3 PET technical procedures manual (https://adni.loni.usc.edu/wp-content/uploads/2012/10/ADNI3_PET-Tech-Manual_V2.0_20161206.pdf). In short, all subjects underwent a 30-min PET scan (6 × 5 min dynamic frames) starting at 75 min after intravenous injection of 370 MBq ± 10% of flortaucipir. Image analysis of 18F-flortaucipir PET scans was performed using the same methods described for 18F-florbetaben PET analysis. Cortical ROIs extracted from the AAL atlas included the mesial temporal (average of amygdala, hippocampus, and parahippocampus), fusiform gyrus, inferior lateral temporal, parietal cortices, and cerebellar gray matter. SUVR was calculated as the ratio of the activity in the cortical ROIs to the activity in the reference region (cerebellar gray matter excluding vermis and anterior lobe cerebellar surrounding the vermis).

Visual assessment

Amyloid PET scans from a subset of 416 participants (n = 65 (yHC), n = 66 (eHC), n = 168 (SCD), n = 44 (MCI), n = 73 (AD)) (datasets #1, #2, #3, and #4) were visually assessed by independent blinded readers using the method described in Seibyl et al. [10]. The readers were blinded to any structural information (CT or MRI) and different for each of the studies included in the manuscript. The subjects used to generate cutoffs for the detection of established Aβ amyloid pathology (dataset #2) and MCI subjects (dataset #4) were read by 3 independent blinded readers with previous experience reading FBB scans and the final assessment was based on the majority read (i.e., agreement of the majority of readers).

SUVR cutoff development and definition of the gray zone

Development of an SUVR cutoff for the detection of early Aβ deposition (SUVRearly)

A group of visually Aβ-negative cognitively normal yHC (dataset #1) were used to develop an SUVR cutoff to detect early amyloid deposition. A Shapiro-Wilk test was applied to ascertain that the distribution of each regional SUVR was not significantly different from the Gaussian distribution. Then, the regional SUVRearly cutoffs were calculated as 2 standard deviations above the mean SUVR of the yHC.

Development of an SUVR cutoff for the detection of established Aβ pathology (SUVRestab)

The established pathology SUVR cutoff was derived using receiver operating characteristic (ROC) analysis to ascertain the optimal threshold for the sensitivity and specificity calculation on a sample of visually Aβ-negative eHC and visually Aβ-positive AD dementia patients (dataset #2) [13]. The SUVR that provided the highest Youden’s index (sensitivity + specificity − 1) was selected. In cases that several SUVR provided the same Youden’s index, the SUVR with higher specificity was selected. Global visual assessment as described by Seibyl et al. was used as the standard of truth [10].

Definition of the “gray zone”

Given the developed SUVR cutoffs, three groups were defined within the SUVR continuum: Aβ-negative subjects (SUVR < SUVRearly), early Aβ deposition or “gray zone” (SUVRearly ≤ SUVR ≤ SUVRestab), and Aβ-positive subjects with established amyloid pathology (SUVRestab < SUVR).

Characterization of earliest in vivo signal and SUVR cutoff assessment

Characterization of earliest in vivo signal in amyloid PET images and topographical distribution

Given that each brain region may have different non-specific binding and dynamic SUVR ranges, direct comparison of SUVR across regions cannot be used to extract the regions showing the earliest amyloid deposition. The assessment of early amyloid deposition assumed that amyloid accumulation follows a logistic growth [32]:

where t is the time through the accumulation process, SUVR(t) is the regional SUVR at time t, NS is the tracer non-specific binding, r is the exponential uninhibited growth rate, K is the carrying capacity, and T50 is the time of half-maximal Aβ carrying capacity. NS, K, r, and T50 could be different for each region. However, the logistic growth model could not be fitted given the cross-sectional nature of the data used in this work (i.e., individual times through the accumulation process are unknown). Instead, half of the maximum amyloid carrying capacity (SUVR(t = T50)) reached when t = T50 was used to identify those regions that show earliest amyloid signal using PET. In this study, it was hypothesized that T50 will be smallest in regions with early amyloid deposition.

where NS was estimated from the regional mean SUVR of the visually Aβ-negative yHCs (NS=SUVRyHC) and K was estimated from the difference between the regional mean of visually Aβ-positive AD dementia subjects (SUVRAD) and SUVRyHC (K = SUVRAD − SUVRyHC).

Then, a regional ΔSUVR was derived to characterize the location of a subject in the AD continuum as follows: ΔSUVR = SUVR − SUVR(t = T50). The ΔSUVR takes positive values in those subjects and regions that are above SUVR(t = T50) and close to the SUVR of subjects with AD dementia and negative values in those subjects and regions that are close to SUVR of yHC. ΔSUVR score was compared across regions. Those regions that reached half of the maximum amyloid carrying capacity (ΔSUVR = 0) earlier were considered the regions that show earliest amyloid deposition. Amygdala, thalamus, and striatum, which have a limited dynamic SUVR range between yHC and subjects with AD dementia due to low tracer accumulation, were not included in the interpretation of ΔSUVRs.

Assessment of Aβ accumulation

In this study, it was hypothesized that subjects with SUVR in the “gray zone” are in the initial stages of Aβ accumulation. To test this hypothesis, Aβ accumulation was assessed in two samples of SCD and MCI subjects with longitudinal 18F-florbetaben PET scans (datasets #3 and #4). To estimate the annual SUVR increase, a linear regression model was fitted to each subject’s data, SUVR = α ⋅ t + β, where α and β are the coefficients of the model, and t is the scan time in years. The annual SUVR increase was obtained from α. The percent of Aβ deposition per year (Aβdep) was determined as Aβdep = 100 ⋅ α/SUVRB where SUVRB is the SUVR at baseline. Subsequently, the average annual SUVR increase (α) in each sample was tested statistically by means of a t-test to demonstrate that those subjects in the “gray zone” are in the process of accumulating Aβ (i.e., (H0 : α = 0; H1 : α > 0). Likewise, annual CL increase (αCL) was estimated using a linear regression model fitted to each subject’s data, CL = αCL t + βCL, where αCL and βCL are the coefficients of the model and t is the scan time in years.

Assessment of tau deposition

In subjects that underwent a tau PET scan (dataset #5), 18F-flortaucipir SUVR (mean ± SD) was estimated in the three cutoff-based groups (Aβ-negative subjects, subjects in the “gray zone”, and Aβ-positive subjects with established amyloid pathology) and compared by means of a t-test.

Sensitivity of visual assessment to detect early amyloid accumulation

In those subjects assessed visually (datasets #1, #2, #3, and #4), the proportion of visually Aβ-positive scans was estimated in the three cutoff-based groups (Aβ-negative subjects, subjects in the “gray zone”, and Aβ-positive subjects with established amyloid pathology) to assess the sensitivity of visual assessment to detect early amyloid accumulation.

Results

Development of SUVRearly cutoff

A sample of cognitively normal yHC was used to develop the SUVR cutoff to detect early amyloid deposition. The distribution of SUVRs in yHC did not statistically differ from a Gaussian distribution being the Shapiro-Wilk test non-significant (p > 0.05) in any of the regions analyzed (Fig. 1, Table 2). The composite SUVR using MRI-derived ROIs in the yHC was 1.16 ± 0.04 (mean ± SD) resulting in a SUVRearly cutoff of 1.25 (Fig. 1, Table 2). The determined SUVRearly cutoff differed across regions ranging from 1.15 (lateral temporal cortex) and 1.45 (posterior cingulate cortex) (Table 2). When the standard CL ROIs were applied, the mean of the yHC was 1.03 ± 0.03 (2.82 ± 5.36 CL) and the resulting cutoff (CLearly) was 1.10 (13.5 CL) (Table 2).

Development of the SUVRestab cutoff

ROC analysis using visual assessment as the standard of truth resulted in SUVRestab cutoffs ranging from 1.26 (lateral temporal and parietal cortices) to 1.47 (posterior cingulate cortex). The SUVR cutoff (MRI-derived ROIs) for the composite region was 1.38 (Fig. 2, Table 3). When the standard CL analysis was applied, the SUVRestab and CLestab cutoff obtained were 1.24 and 35.7 CL, respectively.

Receiver operating characteristic curves obtained using MRI-derived regions of interest (ROIs, left) and centiloid (right) used to derive standardized uptake value ratio cutoffs for the established Alzheimer’s disease pathology from a group of elderly healthy controls (n = 66) and subjects with AD dementia (n = 73, dataset #2)

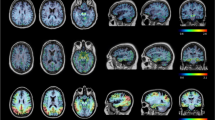

Earliest in vivo signal in amyloid PET images and topographical distribution

Posterior and anterior cingulate cortices followed by precuneus, frontal, and inferior temporal cortices were the regions that showed earlier elevated SUVR values (Fig. 3, left panel). However, given that each region has a different non-specific uptake and SUVR dynamic range, the regional SUVRs were compared against the half maximum amyloid carrying capacity by means of ΔSUVR (ΔSUVR = SUVR − SUVR(t = T50)) to determine the regions that show earliest amyloid accumulation (Fig. 3, right panel). Cingulate cortices (anterior and posterior), precuneus, and orbitofrontal were the regions that first showed pathological Aβ PET tracer retention followed by prefrontal, inferior lateral temporal, parietal, and occipital cortices (Fig. 3, right panel). Other regions that showed tracer retention and differences from yHC were the striatum and the amygdala.

Heat maps of standardized uptake value ratios (SUVRs, left) and ΔSUVRs (=SUVR − SUVR(t = T50)) (right) of all the participants in the analysis (n = 686, datasets #1, #2, #3, #4, and #5). Each column of the heat map represents one subject of the sample. The subjects were sorted according to their composite SUVR (increasing from left to right)

Aβ deposition in subjects with SCD

SUVR histograms derived from a sample of subjects with SCD showed a peak coincident with the Gaussian function fitted to the sample of yHC with a tail with higher SUVRs that increased numbers at follow-up (Fig. 4). The rate of amyloid accumulation increased significantly in those subjects with SUVR in the “gray zone” or with established Aβ deposition in comparison with Aβ-negative subjects (p < 0.002) (Fig. 4). The subjects with SUVRs in the “gray zone” and established Aβ deposition had rates of Aβ accumulation statically different from zero (p < 0.001) (1.66 ± 1.86%/year (composite) and 2.40 ± 2.37%/year (composite), respectively) (Fig. 4, Table 4). Similar results were obtained when the CL analysis was used (1.81 ± 1.86 CL/year (p < 0.001)) (gray zone), 2.38 ± 1.82 CL/year (p < 0.001) (established Aβ pathology)). In general, the Aβ accumulation was significantly larger for subjects in the gray zone and established Aβ deposition than in Aβ-negative subjects (Fig. 4, Table 4).

Histograms of composite standardized uptake value ratios (SUVRs) and centiloids (CLs) for the sample of subjective cognitive decline (SCD) (n = 168, dataset #3) subjects at baseline (first column) and at follow-up (central column). Red and blue lines represent the SUVR abnormality cutoffs for early Aβ detection and established Aβ pathology, respectively. The rate of Aβ accumulation in SCD (and 95% confidence interval in red) in three categories of the composite SUVR continuum (Aβ-negative, gray zone, and established Aβ deposition) is shown on the right column. ROI region of interest

Progression to AD dementia in MCI subjects

SUVR histograms obtained from the MCI subjects showed a broad range of SUVRs (Fig. 5). In general, the rate of amyloid accumulation increased significantly in those subjects with SUVR in the “gray zone” or with established Aβ deposition in comparison with Aβ-negative subjects (p < 0.05). However, the difference between Aβ-negative subjects and subjects in the “gray zone” did not reach statistical significance when CL ROIs were used (Fig. 5). In the composite region, the rate of Aβ accumulation in the “gray zone” (1.51 ± 1.38%/year (p = 0.04) and for “established Aβ deposition” (1.23 ± 1.90%/year (p = 0.004)) was significantly different from zero (Fig. 5) while no accumulation was found in Aβ-negative subjects (− 0.29 ± 1.68%/year (p = 0.74)) (Table 5). None of the Aβ-negative subjects or subjects in the “gray zone” progressed to AD dementia after a 4-year clinical follow-up. Twenty-one subjects (91%) with SUVR above SUVRestab progressed to AD dementia after 4 years (Fig. 5).

Histograms of composite standardized uptake value ratios (SUVRs) and centiloids (CLs) for the sample of mild cognitive impairment (MCI) (n = 44, dataset #4) subjects are shown on the top row. Subjects that progressed to Alzheimer’s disease (AD) dementia after a 4-year clinical follow-up are shown in gray. Red and blue lines represent the SUVR abnormality cutoffs for early Aβ detection and established Aβ pathology, respectively. The rate of Aβ accumulation in MCI subjects (and 95% confidence interval in red) in three categories of the composite SUVR continuum: Aβ-negative, gray zone, and with established Aβ deposition, is shown on the bottom row. ROI region of interest

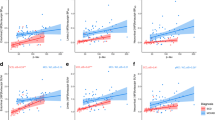

Association between Aβ load and tau deposition

Figure 6 shows the association between amyloid load measured with 18F-florbetaben and tau load measured with [18F] flortaucipir (ρ = 0.35 (parietal)–0.54 (fusiform gyrus) (ρ: Spearman correlation coefficient); p < 0.0001) (Table 6, Fig. 6). Tau deposition was rarely observed in Aβ-negative subjects and subjects in the gray zone: (SUVR(18F-flortaucipir) =1.15 ± 0.08 (Aβ-negative), 1.16 ± 0.09 (gray zone) (Fusiform gyrus)), but increased in subjects with established Aβ pathology (SUVR(18F-flortaucipir) = 1.35 ± 0.24 (Fusiform gyrus)) (Table 6).

Scatter plots of Flortaucipir (FTP) standardized uptake value ratios (SUVRs) versus 18F-florbetaben composite SUVRs using MRI-based regions of interest (ROIs, top row) and FTP SUVRs versus centiloids (CLs, bottom row) (n = 270, dataset #5). Red and blue lines represent the composite SUVR abnormality cutoffs for early Aβ detection and established Aβ pathology, respectively

Sensitivity of visual assessment to detect early amyloid accumulation

Most of the subjects with established Aβ pathology defined either by SUVR (MRI-derived ROIs) or CL cutoffs were visually assessed as positive (93% and 95%, respectively), while all the subjects in the Aβ-negative group were visually assessed as negative (100%). In the gray zone, only 21.4% (MRI-derived ROIs) and 19.6% (CL) of the subjects were visually assessed as positive. The maximum agreement between visual assessment and quantitative assessment was found for SUVR and CL cutoffs in the upper range of the gray zone, while the agreement decreased in the lower range of the gray zone (Fig. 7).

Sensitivities, specificities, and agreement rates between visual assessment and quantitative assessment when using several cutoffs to dichotomize the sample (top row) and composite standardized uptake value ratio (SUVR) versus subject identifier (bottom row) (n = 416) (datasets #1, #2, #3, and #4). Red and blue lines represent the composite SUVR abnormality cutoffs for early Aβ detection and established Aβ pathology, respectively. ROI region of interest, CL centiloid

Discussion

Currently, observational and interventional studies focus on earlier stages of Aβ deposition, where established SUVR cutoffs to discriminate AD dementia subjects from elderly HC are of limited value. In this study, regional and global quantitative SUVR cutoffs were developed for the detection of early amyloid accumulation and established Aβ pathology using 18F-florbetaben PET. A gray zone was defined as the range of SUVR values in subjects having higher SUVR than yHC and less than the values previously used to define visual positivity in patients with AD dementia. The existence of a “gray zone” that may precede visual positivity and the feasibility of identifying subjects in the gray zone using 18F-florbetaben PET were corroborated using two quantitative methods (MRI-derived ROIs and CL ROIs). The population in the “gray zone” represents early stages of Aβ deposition characterized by accelerated Aβ accumulation and pre-AD dementia levels of Aβ burden that may precede the alteration of other biomarkers such as tau deposition or clinical symptoms. Although assessment of tau deposition using Flortaucipir PET in mesial temporal structures could be biased due to adjacent choroid plexus uptake, the association between Aβ and tau was strong also in other regions assessed such as fusiform gyrus and inferior lateral temporal cortex. While the agreement between visual and quantitative assessments was excellent for Aβ-negative subjects and subjects with established Aβ pathology, the agreement was modest in the “gray zone.” In these challenging cases, the use of quantitation may help to detect subtle amyloid accumulation. The appropriate definition of a “gray zone” can improve the detection of emerging Aβ pathology in observational, prevention, and therapeutic trials and is key for the screening of asymptomatic population in clinical trials and detection of subjects that will likely accumulate amyloid. Subjects having amyloid values in the gray zone may be the most likely to respond to pharmacological or non-pharmacological interventions because they have early evidence of disease without the cognitive deficits and neuronal loss that signifies AD.

This study is in agreement with a number of recent reports across different tracers converging to the utility of using two cutoffs for amyloid PET abnormality, an early cutoff around CL = 11–17 where pathology may be emerging, and a second around CL = 29–36 where amyloid burden levels correspond to moderate and frequent neuritic plaques (CERAD stages B–C, [33]) by neuropathology. Early cutoffs of 11, 14, and 17 CL have been reported for the FACEHBI, ALFA+, and AMYPAD Prognostic and Natural History Study studies using Gaussian mixture models [34]. Similarly, Salvadó et al. identified two cutoffs based on a direct comparison with established CSF Aβ42 thresholds: CL = 12 to rule out-amyloid pathology and CL = 29 to denote established pathology [35]. Mormino et al. also showed the biological relevance of slight 11C-PIB elevations in elderly normal control subjects and provided an estimate for the cutoffs defining the “gray zone” using distribution volume ratios [36]. Finally, La Joie et al. and Doré et al. reported using histopathological confirmation gray zones from 12.2–24.4 and 19–28 CLs, respectively [17, 37].

This study also showed that topographical information can help identify increased signal earlier than traditional global cutoffs, with cingulate cortices (anterior and posterior), precuneus, and orbitofrontal cortices being the first regions to show pathological tracer retention, followed by prefrontal, inferior lateral temporal parietal, and occipital cortices. These results agree with previous publications using PET where precuneus, cingulate, and frontal cortices displayed higher PET signal earlier than the remaining neocortical regions [38,39,40]. However, recent publications suggest that other regions such as the banks of the superior temporal, not analyzed in this article, may also show early Aβ deposition and subjects with high Aβ in these regions are at increased risk of cognitive decline [41]. Even though regions with “early” amyloid have been identified in this work, these early elevations are subtle, occasionally may not be detectable at the individual level and the amyloid PET signal is highly correlated across all regions. These subtle differences across regions are consistent with some articles reporting that a sigmoidal model fitting amyloid deposition with the same T50 across brain regions is optimal [32]. In addition, amyloid PET is affected by several technical factors such as the type of camera used, reconstruction methods, corrections applied (e.g., partial volume effect), and quantitative methods used that may have an impact on the regional SUVR estimates. For this reason, topographically defined distribution and early Aβ accumulation measured by PET may not necessarily agree with histopathology findings. Despite these discrepancies with neuropathology results, several studies have shown the utility of amyloid PET topographical quantification in staging AD [21,22,23], determining the risk of subsequent cognitive decline [23, 25], optimal subject selection for anti-amyloid interventional trials [22, 42], and reducing sample size in anti-amyloid interventional trials [43, 44]. Pascoal et al. also showed that the topographical pattern of individuals with MCI that progress to dementia is “traditionally AD-like,” while that of non-converters includes more temporal and occipital regions instead [24]. In this regard, even though CL ROIs and composite SUVR from MRI-derived ROIs provided overall similar results when determining subject in the “gray zone,” the use of CL and composite SUVR is limited in determining the topographical distribution of Aβ load.

As a limitation of this study, it should be mentioned that SUVR cutoff for the detection of established amyloid pathology was derived using visual assessment as a standard of truth and this may bias the proportion of visually positive scans per group. To clarify this potential bias, a Gaussian mixture model was fitted to the whole population of the study (datasets #1, #2, #3, #4, and #5) confirming the cutoffs previously reported in the manuscript (14 and 32 CL), proportion of positive scans per group and accurate definition of the “gray zone” (supplemental material 2). A second limitation is that SUVR may be biased as a surrogate marker of Aβ load by changes in cerebral blood flow (CBF) or radiotracer clearance [45] and SUVR cutoffs may depend on methodological aspects such as equipment, reconstruction, imaging window, image processing, smoothing, and corrections applied. To minimize this methodological limitation, a harmonization procedure was applied to convert all the images into a common resolution as described in Joshi et al. [27]. Even so, the application of cutoffs developed here should be applied with caution to studies using different methods or non-harmonized data.

Conclusions

This study supports the utility of two cutoffs for 18F-florbetaben amyloid PET abnormality defining a “gray zone”: a first cutoff of 13.5 CL that indicated emerging Aβ pathology and a second cutoff of 35.7 CL where amyloid burden levels correspond to established AD neuropathology findings. These cutoffs define a subset of subjects characterized by pre-AD dementia levels of amyloid burden that may precede the alteration of other biomarkers such as tau deposition or clinical symptoms and accelerated amyloid accumulation. Amyloid PET images in the “gray zone” are more likely to be ambiguous by the current binary global visual assessment methodology. At the MCI stage, the determination of different amyloid loads, particularly low amyloid levels, is useful in determining who will eventually progress to dementia. Quantitation of amyloid provides a sensitive measure in these low-load cases and may help to identify a group of subjects most likely to benefit from intervention.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets generated and/or analyzed during the current study are not publicly available.

References

Braak H, Braak E. Frequency of stages of Alzheimer-related lesions in different age categories. Neurobiol Aging. 1997;18(4):351–7.

Villemagne VL, Burnham S, Bourgeat P, Brown B, Ellis KA, Salvado O, et al. Amyloid beta deposition, neurodegeneration, and cognitive decline in sporadic Alzheimer’s disease: a prospective cohort study. Lancet Neurol. 2013;12(4):357–67.

Blennow K, Zetterberg H, Rinne JO, Salloway S, Wei J, Black R, et al. Effect of immunotherapy with bapineuzumab on cerebrospinal fluid biomarker levels in patients with mild to moderate Alzheimer disease. Arch Neurol. 2012;69(8):1002–10.

Uenaka K, Nakano M, Willis BA, Friedrich S, Ferguson-Sells L, Dean RA, et al. Comparison of pharmacokinetics, pharmacodynamics, safety, and tolerability of the amyloid beta monoclonal antibody solanezumab in Japanese and white patients with mild to moderate Alzheimer disease. Clin Neuropharmacol. 2012;35(1):25–9.

Weninger S, Carrillo MC, Dunn B, Aisen PS, Bateman RJ, Kotz JD, et al. Collaboration for Alzheimer’s prevention: principles to guide data and sample sharing in preclinical Alzheimer’s disease trials. Alzheimers Dement. 2016;12(5):631–2.

McDade E, Bateman RJ. Stop Alzheimer’s before it starts. Nature. 2017;547(7662):153–5.

Ritchie CW, Molinuevo JL, Truyen L, Satlin A, Van der Geyten S, Lovestone S. Development of interventions for the secondary prevention of Alzheimer’s dementia: the European Prevention of Alzheimer’s Dementia (EPAD) project. Lancet Psychiatry. 2016;3(2):179–86.

Sperling RA, Jack CR Jr, Aisen PS. Testing the right target and right drug at the right stage. Sci Transl Med. 2011;3(111):111cm33.

Sabri O, Sabbagh MN, Seibyl J, Barthel H, Akatsu H, Ouchi Y, et al. Florbetaben PET imaging to detect amyloid beta plaques in Alzheimer’s disease: phase 3 study. Alzheimers Dement. 2015;11(8):964–74.

Seibyl J, Catafau AM, Barthel H, Ishii K, Rowe CC, Leverenz JB, et al. Impact of training method on the robustness of the visual assessment of 18F-florbetaben PET scans: results from a phase-3 study. J Nucl Med. 2016;57(6):900–6.

Bullich S, Villemagne VL, Catafau AM, Jovalekic A, Koglin N, Rowe CC, et al. Optimal reference region to measure longitudinal amyloid-beta change with 18F-florbetaben PET. J Nucl Med. 2017;58(8):1300–6.

Bullich S, Seibyl J, Catafau AM, Jovalekic A, Koglin N, Barthel H, et al. Optimized classification of 18F-florbetaben PET scans as positive and negative using an SUVR quantitative approach and comparison to visual assessment. Neuroimage Clin. 2017;15:325–32.

Barthel H, Gertz HJ, Dresel S, Peters O, Bartenstein P, Buerger K, et al. Cerebral amyloid-beta PET with florbetaben (18F) in patients with Alzheimer’s disease and healthy controls: a multicentre phase 2 diagnostic study. Lancet Neurol. 2011;10(5):424–35.

Jennings D, Seibyl J, Sabbagh M, Lai F, Hopkins W, Bullich S, et al. Age dependence of brain beta-amyloid deposition in Down syndrome: an [18F] florbetaben PET study. Neurology. 2015;84(5):500–7.

Tuszynski T, Rullmann M, Luthardt J, Butzke D, Tiepolt S, Gertz HJ, et al. Evaluation of software tools for automated identification of neuroanatomical structures in quantitative beta-amyloid PET imaging to diagnose Alzheimer’s disease. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2016;43(6):1077–87.

Villemagne VL, Ong K, Mulligan RS, Holl G, Pejoska S, Jones G, et al. Amyloid imaging with (18)F-florbetaben in Alzheimer disease and other dementias. J Nucl Med. 2011;52(8):1210–7.

Doré V, Bullich S, Rowe CC, Bourgeat P, Konate S, Sabri O, et al. Comparison of 18F-florbetaben quantification results using the standard centiloid, MR-based, and MR-less CapAIBL((R)) approaches: validation against histopathology. Alzheimers Dement. 2019;15(6):807–16.

Ong K, Villemagne VL, Bahar-Fuchs A, Lamb F, Chételat G, Raniga P, et al. (18)F-florbetaben Abeta imaging in mild cognitive impairment. Alzheimers Res Ther. 2013;5(1):4.

Bischof GN, Jacobs HIL. Subthreshold amyloid and its biological and clinical meaning: long way ahead. Neurology. 2019;93(2):72–9.

Fantoni E, Collij L, Lopes Alves I, Buckley C, Farrar G. AMYPAD consortium. The spatial-temporal ordering of amyloid pathology and opportunities for PET imaging. J Nucl Med. 2020;61(2):166–71.

Grothe MJ, Barthel H, Sepulcre J, Dyrba M, Sabri O, Teipel SJ. In vivo staging of regional amyloid deposition. Neurology. 2017;89(20):2031–8.

Mattsson N, Palmqvist S, Stomrud E, Vogel J, Hansson O. Staging beta-amyloid pathology with amyloid positron emission tomography. JAMA Neurol. 2019;76(11):1319–29.

Collij LE, Heeman F, Salvadó G, Ingala S, Altomare D, de Wilde A, et al. Multitracer model for staging cortical amyloid deposition using PET imaging. Neurology. 2020;95(11):e1538–53.

Pascoal TA, Therriault J, Mathotaarachchi S, Kang MS, Shin M, Benedet AL, et al. Topographical distribution of Abeta predicts progression to dementia in Abeta positive mild cognitive impairment. Alzheimers Dement (Amst). 2020;12(1):e12037.

Hanseeuw BJ, Betensky RA, Mormino EC, Schultz AP, Sepulcre J, Becker JA, et al. PET staging of amyloidosis using striatum. Alzheimers Dement. 2018;14(10):1281–92.

Rodriguez-Gomez O, Sanabria A, Perez-Cordon A, Sanchez-Ruiz D, Abdelnour C, Valero S, et al. FACEHBI: a prospective study of risk factors, biomarkers and cognition in a cohort of individuals with subjective cognitive decline. Study rationale and research protocols. J Prev Alzheimers Dis. 2017;4(2):100–8.

Joshi A, Koeppe RA, Fessler JA. Reducing between scanner differences in multi-center PET studies. Neuroimage. 2009;46(1):154–9.

Tzourio-Mazoyer N, Landeau B, Papathanassiou D, Crivello F, Etard O, Delcroix N, et al. Automated anatomical labeling of activations in SPM using a macroscopic anatomical parcellation of the MNI MRI single-subject brain. Neuroimage. 2002;15(1):273–89.

Rowe CC, Ackerman U, Browne W, Mulligan R, Pike KL, O'Keefe G, et al. Imaging of amyloid beta in Alzheimer’s disease with 18F-BAY94-9172, a novel PET tracer: proof of mechanism. Lancet Neurol. 2008;7(2):129–35.

Klunk WE, Koeppe RA, Price JC, Benzinger TL, Devous MD Sr, Jagust WJ, et al. The Centiloid Project: standardizing quantitative amyloid plaque estimation by PET. Alzheimers Dement. 2015;11(1):1–15 e1–4.

Rowe CC, Doré V, Jones G, Baxendale D, Mulligan RS, Bullich S, et al. 18F-Florbetaben PET beta-amyloid binding expressed in centiloids. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2017;44(12):2053–9.

Whittington A, Sharp DJ, Gunn RN. Spatiotemporal distribution of β-amyloid in Alzheimer disease is the result of heterogeneous regional carrying capacities. J Nucl Med. 2018;59(5):822–7.

Mirra SS, Heyman A, McKeel D, Sumi SM, Crain BJ, Brownlee LM, et al. The Consortium to Establish a Registry for Alzheimer’s Disease (CERAD). Part II. Standardization of the neuropathologic assessment of Alzheimer’s disease. Neurology. 1991;41:479–86.

Bullich S. Converging evidence for a “gray-zone” of amyloid burden and its relevance. in AAIC. 2020. Virtual.

Salvadó G, Molinuevo JL, Brugulat-Serrat A, Falcon C, Grau-Rivera O, Suárez-Calvet M, et al. Centiloid cut-off values for optimal agreement between PET and CSF core AD biomarkers. Alzheimers Res Ther. 2019;11(1):27.

Mormino EC, Brandel MG, Madison CM, Rabinovici GD, Marks S, Baker SL, et al. Not quite PIB-positive, not quite PIB-negative: slight PIB elevations in elderly normal control subjects are biologically relevant. Neuroimage. 2012;59(2):1152–60.

La Joie R, Ayakta N, Seeley WW, Borys E, Boxer AL, DeCarli C, et al. Multisite study of the relationships between antemortem [11C]PIB-PET Centiloid values and postmortem measures of Alzheimer’s disease neuropathology. Alzheimers Dement. 2019;15(2):205–16.

Villeneuve S, Rabinovici GD, Cohn-Sheehy BI, Madison C, Ayakta N, Ghosh PM, et al. Existing Pittsburgh Compound-B positron emission tomography thresholds are too high: statistical and pathological evaluation. Brain. 2015;138(Pt 7):2020–33.

Cho H, Choi JY, Hwang MS, Kim YJ, Lee HM, Lee HS, et al. In vivo cortical spreading pattern of tau and amyloid in the Alzheimer disease spectrum. Ann Neurol. 2016;80(2):247–58.

Palmqvist S, Schöll M, Strandberg O, Mattsson N, Stomrud E, Zetterberg H, et al. Earliest accumulation of β-amyloid occurs within the default-mode network and concurrently affects brain connectivity. Nat Commun. 2017;8(1):1214.

Guo T, Landau SM, Jagust WJ. Detecting earlier stages of amyloid deposition using PET in cognitively normal elderly adults. Neurology. 2020;94(14):e1512–24.

Guo T, Dukart J, Brendel M, Rominger A, Grimmer T, Yakushev I. Rate of beta-amyloid accumulation varies with baseline amyloid burden: implications for anti-amyloid drug trials. Alzheimers Dement. 2018;14(11):1387–96.

Insel PS, Mormino EC, Aisen PS, Thompson WK, Donohue MC. Neuroanatomical spread of amyloid beta and tau in Alzheimer’s disease: implications for primary prevention. Brain Commun. 2020;2(1):fcaa007.

Lopes Alves I, Collij LE, Altomare D, Frisoni GB, Saint-Aubert L, Payoux P, et al. Quantitative amyloid PET in Alzheimer’s disease: the AMYPAD prognostic and natural history study. Alzheimers Dement. 2020;16(5):750–8.

Bullich S, Barthel H, Koglin N, Becker GA, De Santi S, Jovalekic A, et al. Validation of noninvasive tracer kinetic analysis of (18)F-Florbetaben PET using a dual-time-window acquisition protocol. J Nucl Med. 2018;59(7):1104–10.

Acknowledgements

The FACEHBI study group: Abdelnour C1,2, Aguilera N1, Alarcón-Martín E1, Alegret M1,2, Alonso-Lana S1, Berthier M3 Buendia M1, Campos F4, Cañabate P1,2, Cañada L1, Cuevas C1, de Rojas I1, Diego S1, Espinosa A1,2, Esteban-De Antonio E1, Gailhajenet A1, García P1, Giménez J5, Gómez-Chiari M5, Guitart M1, Hernández I1,2, Ibarria, M1, Lafuente A1, Lomeña F4, López-Cuevas R1, Masip E1, Martín E1, Martínez J1, Mauleón A1, Moreno M1, Moreno-Grau S1,2, Montrreal L1, Niñerola A4, Nogales AB1, Núñez L6, Orellana A1, Ortega G1, Páez A6, Pancho A1, Pelejà E1, Pérez-Cordon A1, Pérez-Grijalba V7, Perissinotti A4, Pesini P7, Preckler S1, Roberto N1, Romero J7, Ramis M1, Rosende-Roca M1, Ruiz A1,2, Sarasa M7, Tejero MA5, Torres M6, Valero S1,2, Vargas L1, Vivas A5. (1Fundacio ACE Institut Català de Neurociències Aplicades, Research Center and Memory Unit – Universitat Internacional de Catalunya. Barcelona, Spain; 2CIBERNED, Center for Networked Biomedical Research on Neurodegenerative Diseases, National Institute of Health Carlos III, Ministry of Economy and Competitiveness, Spain. 3Cognitive Neurology and Aphasia Unit (UNCA). University of Malaga. 4Servei de Medicina Nuclear, Hospital Clínic i Provincial, Barcelona, Spain; 5Departament de Diagnòstic per la Imatge. Clínica Corachan, Barcelona, Spain; 6Grifols®, 7Araclon Biothech®. Zaragoza, Spain).

Funding

Part of the data were acquired in clinical studies funded by Bayer Pharma AG or Piramal Imaging.

Part of the data collection and sharing for this project was funded by the Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative (ADNI) (National Institutes of Health Grant U01 AG024904) and DOD ADNI (Department of Defense award number W81XWH-12-2-0012). ADNI is funded by the National Institute on Aging, the National Institute of Biomedical Imaging and Bioengineering, and through generous contributions from the following: AbbVie, Alzheimer’s Association; Alzheimer’s Drug Discovery Foundation; Araclon Biotech; BioClinica, Inc.; Biogen; Bristol-Myers Squibb Company; CereSpir, Inc.; Cogstate; Eisai Inc.; Elan Pharmaceuticals, Inc.; Eli Lilly and Company; EuroImmun; F. Hoffmann-La Roche Ltd. and its affiliated company Genentech, Inc.; Fujirebio; GE Healthcare; IXICO Ltd.; Janssen Alzheimer Immunotherapy Research & Development, LLC.; Johnson & Johnson Pharmaceutical Research & Development LLC.; Lumosity; Lundbeck; Merck & Co., Inc.; Meso Scale Diagnostics, LLC.; NeuroRx Research; Neurotrack Technologies; Novartis Pharmaceuticals Corporation; Pfizer Inc.; Piramal Imaging; Servier; Takeda Pharmaceutical Company; and Transition Therapeutics. The Canadian Institutes of Health Research is providing funds to support ADNI clinical sites in Canada. Private sector contributions are facilitated by the Foundation for the National Institutes of Health (www.fnih.org). The grantee organization is the Northern California Institute for Research and Education, and the study is coordinated by the Alzheimer’s Therapeutic Research Institute at the University of Southern California. ADNI data are disseminated by the Laboratory for Neuro Imaging at the University of Southern California.

Part of the data used in the preparation of this article were obtained from the Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative (ADNI) database (adni.loni.usc.edu). As such, the investigators within the ADNI contributed to the design and implementation of ADNI and/or provided data but did not participate in the analysis or writing of this report. A complete listing of ADNI investigators can be found at http://adni.loni.usc.edu/wp-content/uploads/how_to_apply/ADNI_Acknowledgement_List.pdf

The FACEHBI study was supported by funds from Fundació ACE Institut Català de Neurociències Aplicades, Grifols, Life Molecular Imaging, Araclon Biotech, Alkahest, Laboratorio de análisis Echevarne, and IrsiCaixa.

This work has received support from the EU-EFPIA Innovative Medicines Initiatives 2 Joint Undertaking (grant no. 115952). This communication reflects the views of the authors and neither IMI nor the European Union and EFPIA are liable for any use that may be made of the information contained herein.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors made a substantial contribution in interpreting of the study results and revising the manuscript critically for important intellectual content and approved the final version to be published. SB and NRV performed image and statistical analysis and prepared the first versions of the manuscript. SB, NRV, NK, AM, AP, AJ, SDS, and AS contributed to the concept, design, and interpretation of the study. VV, VD, and CR participated in the acquisition and interpretation of data from MCI subjects MM, AS, JPT, OSG, LT, and MB participated in the acquisition and interpretation of results from subjective memory complainers (FACEHBI study). HB and OS participated in the acquisition and interpretation of results from elderly HC and AD subjects. JS participated in the acquisition and interpretation of results from the young healthy volunteers. SML participated in the interpretation of results from the young healthy volunteers and ADNI participants.

Authors’ information

Authors are on behalf of the AMYPAD consortium:

Santiago Bullich, Núria Roé-Vellvé, Marta Marquié, Ángela Sanabria, Juan Pablo Tartari, Oscar Sotolongo-Grau, Norman Koglin, Andre Müller, Audrey Perrotin, Aleksandar Jovalekic, Lluís Tárraga, Andrew W. Stephens, Mercè Boada.

Authors are on behalf of the FACEHBI study group:

Marta Marquié, Ángela Sanabria, Juan Pablo Tartari, Oscar Sotolongo-Grau, Lluís Tárraga, Mercè Boada.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

All studies were conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and after approval of the local ethics committees of the participating centers. All participants (or their legal representatives) provided written informed consent prior to recruitment.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

SB, NRV, NK, AM, AP, AJ, and AS are employees of Life Molecular Imaging GmbH (formerly Piramal Imaging GmbH). SDS is an employee of Eisai Inc. and a former employee of Life Molecular Imaging Inc. (formerly Piramal Pharma Inc). HB and OS received research support, consultant honoraria, and travel expenses from Piramal Imaging GmbH. Victor L. Villemagne has received speaker’s honoraria from Piramal Imaging, GE Healthcare, Avid Pharmaceuticals, AstraZeneca, and Hoffmann-La Roche and consulting fees for Novartis, Lundbeck, Abbvie, Shanghai Green Valley Pharmaceutical Co. LTD, and Hoffmann-La Roche. Christopher C. Rowe has received research grants from Bayer Schering Pharma, Piramal Imaging, Avid Radiopharmaceuticals, Navidea, GE Healthcare, AstraZeneca, and Biogen. John Seibyl holds equity in Invicro and consulting fees from LMI, Roche, Biogen, AbVie, and Invicro. M. Boada has received research funds from the following private donors: Grifols SA, Caixabank S.A., Piramal Imaging, Araclon Biotech, Laboratorios Echevarne, Fundació Castell de Peralada, and Fundació La Pedrera and has participated in advisory boards of Araclon Biotech, Biogen, Bioibérica, Eisai, Grifols, Lilly, Merck, Nutricia, Roche, Schwabe Farma, Servier, and Kyowa Kirin.

No other potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Bullich, S., Roé-Vellvé, N., Marquié, M. et al. Early detection of amyloid load using 18F-florbetaben PET. Alz Res Therapy 13, 67 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13195-021-00807-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13195-021-00807-6