Abstract

Background

The role of neuromuscular blocking agents (NMBAs) in coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) is not fully elucidated. Therefore, we aimed to investigate in COVID-19 patients with moderate-to-severe ARDS the impact of early use of NMBAs on 90-day mortality, through propensity score (PS) matching analysis.

Methods

We analyzed a convenience sample of patients with COVID-19 and moderate-to-severe ARDS, admitted to 244 intensive care units within the COVID-19 Critical Care Consortium, from February 1, 2020, through October 31, 2021. Patients undergoing at least 2 days and up to 3 consecutive days of NMBAs (NMBA treatment), within 48 h from commencement of IMV were compared with subjects who did not receive NMBAs or only upon commencement of IMV (control). The primary objective in the PS-matched cohort was comparison between groups in 90-day in-hospital mortality, assessed through Cox proportional hazard modeling. Secondary objectives were comparisons in the numbers of ventilator-free days (VFD) between day 1 and day 28 and between day 1 and 90 through competing risk regression.

Results

Data from 1953 patients were included. After propensity score matching, 210 cases from each group were well matched. In the PS-matched cohort, mean (± SD) age was 60.3 ± 13.2 years and 296 (70.5%) were male and the most common comorbidities were hypertension (56.9%), obesity (41.1%), and diabetes (30.0%). The unadjusted hazard ratio (HR) for death at 90 days in the NMBA treatment vs control group was 1.12 (95% CI 0.79, 1.59, p = 0.534). After adjustment for smoking habit and critical therapeutic covariates, the HR was 1.07 (95% CI 0.72, 1.61, p = 0.729). At 28 days, VFD were 16 (IQR 0–25) and 25 (IQR 7–26) in the NMBA treatment and control groups, respectively (sub-hazard ratio 0.82, 95% CI 0.67, 1.00, p = 0.055). At 90 days, VFD were 77 (IQR 0–87) and 87 (IQR 0–88) (sub-hazard ratio 0.86 (95% CI 0.69, 1.07; p = 0.177).

Conclusions

In patients with COVID-19 and moderate-to-severe ARDS, short course of NMBA treatment, applied early, did not significantly improve 90-day mortality and VFD. In the absence of definitive data from clinical trials, NMBAs should be indicated cautiously in this setting.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Since early 2020, SARS-CoV-2 infections have placed tremendous burden on patients and international healthcare services [1]. A high proportion of diseased patients require hospitalization, and a small subset with severe coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) become critically ill and require invasive mechanical ventilation (IMV) for life-threatening respiratory failure [2,3,4,5]. High mortality has been reported in this subpopulation [4, 6,7,8,9], irrespective of survival benefits from established treatments, such as corticosteroids and IL-6 receptor antagonists [10, 11].

Neuromuscular blocking agents (NMBAs) have been commonly used for acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) [12, 13] to reduce patient–ventilator asynchrony and—in the context of severely damaged and poorly compliant lungs—to improve oxygenation, while minimizing the work of breathing and risks of barotrauma. International studies have confirmed the use of NMBAs in up to 26% of ARDS patients [14]. Yet, conflicting results were provided by large randomized clinical trials, such as the ACURASYS [15] and ROSE trials [16], and indication, efficacy, and safety on the use of NMBAs in such patients remain uncertain.

The severe respiratory failure associated with COVID-19 has been described as a form of ARDS, and the potential benefits of supportive treatments have largely been extrapolated from evidence in non-COVID-19-related ARDS. Thus, many COVID-19 patients have been treated with NMBAs [17, 18], and in some areas even shortage of these medications has been reported [19], especially during the early phase of the pandemic. To the best of our knowledge, no international studies have clearly elucidated the effects of NMBAs on mortality in COVID-19 patients. Interestingly, in a multicenter observational study, Courcelle et al. [20] reported that the duration of NMBA treatment in this population was often longer than 48 h and not associated with shorter duration of IMV.

To further delineate the role of NMBA in ventilated COVID-19 patients, data extracted from the multicenter registry of the international COVID-19 Critical Care Consortium incorporating the ExtraCorporeal Membrane Oxygenation for 2019 novel Coronavirus Acute Respiratory Disease (COVID-19–CCC/ECMOCARD) were examined. Our hypothesis was that in patients with microbiologically confirmed COVID-19 and moderate-to-severe ARDS, no significant difference in 90-day hospital mortality was to be found between populations who received or not early NMBAs. Thus, the primary goal of this study was to identify difference in 90-day mortality, through propensity score (PS)-adjusted analysis, between patients who received or not a short course of NMBAs, within 48 h from commencement of IMV.

Methods

Study design

This was a comparative study in which mechanically ventilated COVID-19 patients with moderate-to-severe ARDS, who received an early short course of NMBAs, were compared with patients who did not receive NMBA or underwent NMBA treatment only on the day of commencement of IMV to explore the impact on in-hospital mortality during a follow-up period up to 90 days. Of note, the STROBE (Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology) guidelines were used to ensure the reporting of this observational study [21].

Study population and settings

Inclusion criteria

We studied a convenience sampling of patients (≥ 16 years old) with microbiologically confirmed SARS-CoV-2 infection, via rapid nucleic acid amplification test (NAAT) or antigen tests, who were admitted to an intensive care unit (ICU) from February 1, 2020, through October, 31, 2021, at any of the COVID-19 Critical Care Consortiums participating hospitals. In addition, patients were selected if they presented with moderate-to-severe ARDS, defined by a ratio of the partial pressure of arterial oxygen to the fraction of inspired oxygen of < 150 mm Hg [16], within 48 h from commencement of IMV.

Exclusion criteria

We excluded patients with unrecorded date of commencement of IMV or who were transferred from other institutions, after commencement of IMV. In addition, we excluded from the primary analysis all patients with continuous use of NMBA for periods longer than 3 days, and intermittent use of NMBA within a 3-day period of treatment.

Variables, data sources, and measurements

Data on demographics, comorbidities, clinical symptoms, and laboratory results were collected by clinical and research staff of the participating ICUs in an electronic case report form [22]. Details of respiratory and hemodynamic support, physiological variables, and laboratory results were collected daily, with worst daily values recorded preferentially. Duration of IMV, length of ICU and hospital stays, and hospital mortality were also recorded.

Study groups

In line with previous therapeutic protocols applied in patients with moderate-to-severe ARDS [15, 16], we aimed to appraise a short course of NMBAs, applied early during the course of IMV. Thus, patients were assigned to the following study groups.

NMBA treatment

Use of NMBA treatment for at least 48 h and up to 3 consecutive days, initiated early, within 48 h from commencement of IMV.

Control

No use of NMBAs or administration only on the day IMV was commenced.

Of note, the time of first NMBAs administration was not recorded on the case report form; thus, the treatment group was designed to include up to 3 consecutive days of NMBAs exposure to ensure that at least 2 days of full treatment were achieved in most of the patients, even if treatment commenced during the night or a single NMBA dose was given upon endotracheal intubation. In addition, patients who were tracheally intubated and transferred from institutions not collaborating with the COVID-19-CCC/ECMOCARD were excluded from the analysis to avoid enrolment of subjects who might have received NMBA prior to study monitoring. Recording of NMBA use was censored at 28 days from ICU admission, or upon discharge from the ICU or death, whichever occurred first.

Outcomes

The primary objective was comparison between groups in 90-day in-hospital mortality, through PS matching analysis. Secondary objectives were the numbers of ventilator-free days (days since successful weaning from mechanical ventilation) between day 1 and day 28 and between day 1 and day 90 in the PS-matched population. VFD was calculated as follows: VFDs = 0 if subject died in hospital within 28 or 90 days of mechanical ventilation; VFDs = 28 or 90 − x if successfully liberated from ventilation x days after initiation; VFDs = 0 if the subject was mechanically ventilated for more than 28 or 90 days.

Data source

We analyzed the COVID-19-CCC/ECMOCARD study dataset. COVID-19-CCC/ECMOCARD is an international, multicenter, observational cohort study ongoing in 354 hospitals across 54 countries (Additional file 1: Appendix). The full study protocol has been published elsewhere [22]. The COVID-19-CCC/ECMOCARD observational study was reviewed under the National Mutual Acceptance scheme by the Alfred Health Human Research Ethics Committee on February 27, 2020. The ethics committee certified that the study protocol met the requirements of the National Statement on Ethical Conduct in Human Research (2007), granting approval on March 2, 2020. In addition, in accordance with the Office of the Health Services Commissioners Statutory Guidelines on Research issued for the purposes of Health Privacy Principles, the Alfred Health Human Research Ethics Committee granted a waiver of consent for the collection, use, and disclosure of participants health and personal information. Subsequently, the protocol was approved by all international participating hospitals prior to data collection and waiver of consent was granted in all centers.

Data management and quality

The COVID-19 Consortium collaborates with the International Severe Acute Respiratory and Emerging Infection Consortium (ISARIC) group [23] and their Short PeRiod IncideNce sTudy of Severe Acute Respiratory Infection (SPRINT-SARI) [24] project. De-identified patient data are recorded by data collectors at each collaborating site via the REDCap (Vanderbilt/NIH/NCATS UL1 TR000445 v.10.0.23) electronic data capture tool, using instances hosted at the University of Oxford (UK), University College Dublin (Ireland), Monash University (Australia), and The University of Queensland (Australia). A detailed data dictionary was provided to all sites to assist in data collection. In addition, biweekly drop-in data sessions were scheduled to assist with all queries that data collectors might have. Importantly, the database quality audits of the COVID-19 Consortium dataset are a continuing and intensive process encompassing (1) data cleaning rules; (2) checks for outliers; (3) filtering rules setup during the initial development of the case report form, which was periodically monitored/adjusted; and (4) data completeness checks. Finally, in the case any issue was detected during monitoring of data quality, or statistical analysis, these matters were pursued to address any data collection/process limitation in a timely manner, often including follow-up with the site that entered the data for value verification and correction where appropriate.

Statistical analyses

Categorical data are presented as frequency and percentage, while continuous data as mean and standard deviation (SD; normally distributed) and median and interquartile range (IQR; non-normally distributed). Normality of continuous data was reviewed via visual inspection of histograms. Bivariate comparisons between patients receiving NMBA treatment and controls were compared using Fishers exact test, Students unpaired t test, or the Mann–Whitney U test for categorical, normally, and non-normally distributed continuous variables, respectively.

Analyses were performed to examine the relationship between the primary outcome—mortality censored at 90 days post-commencement of IMV—and NMBA treatment. Patients entered the study analysis once they commenced IMV. As an imbalance in several characteristics at ICU admission between the study groups was noted, propensity score (PS) matching analysis was undertaken to balance these patient characteristics. Matching was undertaken, in preference to other techniques involving propensity scores, to best mimic the results of a randomized controlled trial. Baseline features considered potential variables for inclusion in the PS calculation were demographic and clinical characteristics with either a documented relationship with mortality or a baseline imbalance. Variables with more than 5% missing data were not considered. Based on the available literature on risk factors associated with mortality in severe COVID-19, the following covariates were included during PS modeling: age, sex, region (reference group: North America), time from symptom onset to hospital admission and baseline comorbidities (PaO2/FiO2 within 48 h from commencement of IMV, hypertension, chronic cardiac disease, chronic kidney disease, obesity). Matched cohorts were constructed based on the logit of the PS using nearest-neighbor matching with a caliper width of 0.2 and replacement to promote better balance, and accounting for the estimation of the standard errors. Rubins B [25] (a summation measure of bias with value < 25% indicating adequate balance) and Rubins R (0.5–2.0 indicating appropriate balancing) statistics were initially calculated to assess the success of the matching (i.e., if the resulting matched cohort had balanced characteristics). Standardized mean differences for all covariates, before and after matching, were then estimated, with an absolute difference of 10% or greater considered indicative of imbalance [26, 27].

Following PS matching, survival curves were generated for the matched sample to compare patients undergoing NMBA treatment against control. Finally, multivariable Cox regression models were constructed to assess the effect of NMBA treatment on outcome—incorporating robust estimators of variance to account for matched observations—as well as investigating effect modification on the association between mortality and NMBA by concomitant use of corticosteroids and respiratory failure severity. Covariates considered for inclusion in the multivariable Cox regression were laboratory results upon admission, treatments received and ventilator settings; covariates with known relationship with mortality in COVID-19 patients available in this dataset with less than 5% missing data were included in the final model. Where potential covariates were correlated, the most relevant clinical variable was chosen for inclusion in the model to avoid multicollinearity and the violation of model assumptions. Continuous covariates were standardized by subtracting the mean and dividing by the standard deviation to facilitate meaningful interpretation of the hazard ratios. Multiple imputation was not undertaken, and complete case analysis was performed [28]. Assumptions of the Cox regression model, particularly the proportional hazards assumption, were evaluated using test of the Schoenfeld residuals, as well as graphical exploration of the log–log plot; the proportional hazards assumption was met. Competing risk regression was performed to assess the secondary outcomes of VFDs at 28 and 90 days post-starting of IMV [29].

Sensitivity analyses

Considering the observational nature of our report and potential limitations related to PS matching, we also balanced baseline patient characteristics by weighting each individual in the analysis, by the inverse probability of receiving exposure to NMBAs (inverse probability of treatment weighting [IPTW]) [30]. In addition, as the dataset did not report exact NMBA administration practice, the following sensitivity analyses were conducted to confirm the results of the primary analysis: (1) in patients with clinically suspected and microbiologically confirmed COVID-19, with the treatment group defined as per the primary analysis; and in the treatment group only including patients who received NMBAs (2) continuously for 2 days; (3) continuously for 3 days; and (4) continuously for more than 3 days.

Of note, a post hoc power calculation was undertaken, as a convenience sample was being used. In the unmatched cohort, assuming type I error of 0.05, as well as the rate of primary outcome and study group size as reported in the results, the analysis had 98% power, adequate to undertake and report on the analyses of interest. Data were analyzed using StataSE version 17.0 (StataCorp Pty Ltd., College Station, Texas). Any two-tailed p value less than 0.05 was considered significant. No correction was made for multiple comparisons.

Results

Study population

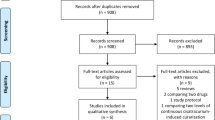

There were 11,873 patients with microbiologically confirmed, or suspected, COVID-19 admitted to 244 hospitals between February 1, 2020, and October 31, 2021. After excluding 3244 patients because of lack of microbiological confirmation of SARS-CoV-2 infection and 1844 patients who were transferred from non-collaborating centers, or transferred out while still on mechanical ventilation, 4616 patients who were on IMV were included in the primary analysis (Fig. 1). Figure 2 shows enrolment rate of those mechanically ventilated patients by date of ICU admission. A matched cohort based on propensity scores was generated, with 210 patients who underwent NMBA treatment and 210 patients as control group. Overall, baseline characteristics were balanced in the propensity score-matched cohort. The mean age was 60.3 years (standard deviation [SD] 13.2 years) (Table 1) and 296 (70.5%) were male. The mean acute physiology and chronic health evaluation (APACHE) II score was 19.5 (SD 11.6; N = 117). In the NMBA treatment and control group, respiratory system compliance was 32.5 mL/cmH2O (SD 12.6) and 33.9 (SD 12.2), respectively, and driving pressure was 22.7 cmH2O (SD 7.5) and 22.4 (SD 8.6). The most common comorbidities among patients in the PS-matched cohort were hypertension (239, 56.9%), obesity (172, 41.1%), and diabetes (125, 30.0%).

NMBA therapy

In the full unmatched cohort, 180 (74.4%) patients received NMBAs for 48 h and 62 (25.6%) for 3 days, while in the control group, 1151 (67.3%) patients received NMBAs only on the day IMV started, and 560 (32.7%) never received NMBAs. In the PS-matched cohort, NMBA treatment was noted in 210 patients. Early use of NMBAs for 48 h was reported in 160 (76.2%) of the patients, while 50 (23.8%) patients received NMBAs for 3 days. In the matched control group, patients never received NMBAs, not even upon the day IMV started. NMBA was provided on average 1 day after ICU admission (N = 207; IQR 0–2 days). The median length from commencement of IMV to initiation of NMBA therapy was 0 days (IQR 0–0 days).

ICU management

In the PS-matched cohort, as summarized in Table 2, PaO2/FiO2 was 88.6 (SD 29.7) vs 86.0 (SD 30.7), in NMBA treatment and control group, respectively. Upon IMV commencement, patients who received NMBA treatment presented PaCO2 of 51.0 mmHg (SD 13.7) vs 48.0 mmHg (SD 15.5) in those who did not. Positive end-expiratory pressure in those undergoing NMBA treatment or not was 12.8 cmH2O (SD 3.3) vs 11.9 cmH2O (SD 3.1), respectively. As for adjunctive therapies, extracorporeal membrane oxygenation, renal replacement therapy, and recruitment maneuvers were provided more frequently to patients who received NMBA treatment (Table 3). Pneumothorax occurred in 21 (10.4%) and 19 (9.6%) of the patients undergoing NMBA treatment or not, respectively.

Primary outcome: 90-day in-hospital mortality

The Kaplan–Meier (Fig. 3A) (log rank test p < 0.001) and the Cox regression model (unadjusted HR 1.78; 95% CI 1.38, 2.30; p < 0.001) confirmed that NMBA treatment was associated with increased mortality risk. The PS-matched cohort analysis comprised 210 patients in the NMBA treatment group vs 210 controls (using replacements). The summaries of balance for unmatched and matched critical parameters are depicted in Fig. 4. Kaplan–Meier curves (Fig. 3B) (log rank p = 0.537) showed no effect of NMBA treatment on mortality, which was also corroborated by the Cox regression model (unadjusted HR = 1.12, 95% CI 0.79, 1.59, p = 0.534). The lack of association with 90-day mortality was consistent after adjusting for smoking habit and critical therapeutic covariates (adjusted HR 1.07; 95% CI 0.72, 1.61, p = 0.729) (Table 4). In subgroup analyses, PaO2/FiO2 and the concomitant use of corticosteroids did not alter negative NMBA association with mortality.

Unadjusted Kaplan–Meier event curves for in-hospital mortality from commencment of invasive mechanical ventilation to 90 days. A Before propensity score matching, 90-day ICU Kaplan-Meier curves differed between patients undergoing up to three-day NMBA therapy, within 48 hours from commencement of IMV, in comparison with those who did not (N = 1953, p < 0.001). B After propensity score matching, no difference in survival between patients undergoing NMBA therapy in comparison with those who did not was found (N = 420, due to equally sized cohorts post propensity score matching, P = 0.537). NMBA neuromuscular blocking agent, ICU intensive care unit

Sensitivity analyses confirmed the lack of association between NMBA treatment and 90-day mortality, when inverse probability weighting analysis was applied (adjusted HR 1.28; 95% CI 0.89, 1.84; p = 0.187) and in the analysis of the cohort of patients with clinically suspected and microbiologically confirmed COVID-19 (adjusted HR 1.44; 95% CI 0.99, 2.09, p = 0.055) (Table 5). In addition, when analyses were restricted to only 2 days (Table 6) or 3 days of NMBA treatment (Table 7), similar insignificant effect on 90-day mortality was found. Conversely, sensitivity analysis exploring continuous NMBA treatment beyond 3 days (Table 8) showed increased risk of 90-day mortality (adjusted HR 1.73, 95% CI 1.22, 2.37, p = 0.001). In this context, the reported median duration of NMBA treatment was 6 days (IQR 5–10).

Secondary outcome: ventilator-free days

In the PS-matched cohort at 28 days after commencement of IMV, VFD were 16 (IQR 0–25) in patients undergoing NMBA treatment and 25 (IQR 7–26) in the control group, and the sub-hazard ratio is 0.82 (95% CI 0.67, 1.00, p = 0.055). However, at 90 days after commencement of IMV, VFD were 77 (IQR 0–87) in patients undergoing NMBA treatment and 87 (IQR 0–88) in the control group; HR 0.86 (95% CI 0.69, 1.07; p = 0.177).

Discussion

To the best of our knowledge, this is the largest, international observational study of patients with COVID-19 requiring mechanical ventilation to assess the impact of short-course NMBA treatment, commenced early during IMV, on 90-day in-hospital mortality. We found that NMBA use was common, specifically at European sites, and frequently applied in patients who presented hypercapnic and required higher levels of PEEP upon commencement of IMV. PS-matching analysis confirmed that early NMBA treatment did not result in lower mortality, while post hoc sensitivity analysis found increased mortality risk when NMBAs use was extended beyond 3 days. In addition, at 28 and 90 days, there were no between-group differences in days free of mechanical ventilation.

NMBAs are commonly used in critically ill patients who require IMV, but this practice has considerably changed throughout the years. In the 1980s, a survey from Great Britain reported NMBA administered in 90% of the patients on IMV [13], while in 2005 data from an international large cohort of mechanically ventilated patients reported NMBAs use merely in 13% of the patients [31]. The most recent clinical practice guidelines by the Society of Critical Care Medicine specified various indications for the use of NMBA in critically ill adult patients [32], among those patients with ARDS and PaO2/FiO2 < 150. In line with the original findings by Gainnier et al. demonstrating consistent oxygenation improvement in ARDS patients undergoing a 48-h course of NMBA [33], the confirmatory ACURASYS trial found that early administration of continuous cisatracurium for 48 h improved 90-day survival [15] and reduced risk of barotrauma. However, subsequent results from the Reevaluation of Systemic Early Neuromuscular Blockade (ROSE) trial failed to show reductions in mortality [16]. Meta-analyses emphasized potential limitations of those previous trials, i.e., heterogeneity in the use of sedation and prone positioning, selection bias, and crossover between treatment groups. Thus, to date, available evidence supports the use of NMBAs to reduce risks of barotrauma and to improve oxygenation [34,35,36], but without clear advantage in survival rate. ARDS caused by COVID-19 has broad similarities with historic ARDS caused by other etiologies [18, 37,38,39], although pulmonary blood flow derangement and resulting pulmonary shunt seem to play a primary role in COVID-19 ARDS [40]. As a result, various interventions previously employed for ARDS, such as prone position [41], ECMO [42], and NMBAs [20], were extensively applied in the COVID-19 population.

In the current study, we describe COVID-19 patients who required mechanical ventilation and who presented with moderate-to-severe hypoxemia. Various small case reports have demonstrated substantial ventilatory asynchrony in these patients [43,44,45] and adverse sequelae, such as pneumothorax or pneumomediastinum [46,47,48]. Patients receiving NMBA also frequently required adjunctive therapies for ARDS, suggesting that the severity of disease was a main driver in the use of these drugs. The COVID-19 population subset investigated in our analyses provides further value to our study; indeed, we identified patients with moderate-to-severe ARDS who received, early, a short course of NMBAs. This is in line with protocols applied in previous large randomized trials [15, 16]. Furthermore, in comparison with the ACURASYS and ROSE trials, we found that the COVID-19 population presented similar baseline impairment in respiratory function, and as in the ROSE trial, low tidal volume and high PEEP were applied and resulted in comparable airway plateau pressure. However, prone position was used much more frequently in the COVID-19 population and the improvements associated with its use [49, 50] might have offset any additional benefit related to NMBAs.

Courcelle and collaborators specifically investigated the effects of NMBAs in COVID-19 patients enrolled in French/Belgian ICUs. After PS matching, they did not find a significant difference in 28-day mortality [20]. Similar to these preliminary findings, our international, larger multicenter investigation also found no improvement in 90-day mortality in patients receiving a short course of NMBAs. Moreover, Courcelle found a median duration of NMBA use of 5 days; conversely, our study appraised only patients who received continuous NMBAs up to 3 days, and interestingly, we found higher hazard ratio of 90-day mortality when the use of NMBAs was extended more than 3 days. This finding provides further evidence on the risks associated with NMBAs in COVID-19 patients. Relative to Courcelles PS-matched cohort, our matched population was similar in age, gender proportion, and BMI and initial ventilatory settings. Yet, in the French/Belgian study, prone positioning was applied in over 90% and ECMO in 15% of the patients, in line with French expert consensus guidelines recommendations [51] and evidence in favor of the aforementioned interventions in COVID-19 patients [42, 50, 52]. Conversely, our dataset encompassed a global population of critically ill COVID-19 patients, including ICU centers both with and without access to modalities such as prone position and ECMO, which were applied in up to 69.6% and 16.7%, respectively. In the early waves of the pandemic, centers with the highest patient numbers acknowledged that treatments, such as prone positioning, could sometimes not be accomplished, due to staffing limitations and patient safety concerns [11]. Similarly, NMBA use at centers with overwhelming ICU surge may also be greater than in less resource-constrained environments.

Non-depolarizing NMBAs inhibit the acetylcholine (Ach) receptor on the motor endplate and are available as aminosteroid or benzylisoquinolinium compound, the latter being the first choice for ARDS patients [53]. Renal and hepatic disease can drastically prolong the clearance of aminosteroid NMBAs, and in these conditions benzylisoquinolinium agents are preferred, since they undergo spontaneous degradation via Hofmann elimination. The NMBA class used was not recorded in our dataset, but severe liver and chronic kidney diseases were present in only 2.9 and 5.7% of the patients treated with NMBAs, respectively. Of note, COVID-19 can cause a broad variety of neurological symptoms and sequelae [54] and has been associated with the development of anti-Ach receptors antibodies [55] and myasthenia gravis [56]. Hence, comprehensive research is needed in this field to elucidate whether underlying neurological mechanisms associated with COVID-19 lead to an increased risk of death when NMBA are administered, and caution should be applied.

Strengths and limitations

To date, this is the first international report of a large group of mechanically ventilated COVID-19 patients with severe disease to investigate the effects of NMBA. Employing comprehensive PS matching analysis, we demonstrated no improvement in mortality with NMBA use. These findings were consistently corroborated in sensitivity analysis applying inverse probability of treatment weighting. In addition, we provided inferences not limited by clinical practice specific to single-country studies. Nonetheless, certain limitations must be highlighted. First, although we conducted a comprehensive comparative PS-matched analysis that resulted in significant homogeneity in the evaluated sub-cohorts, the observational nature of our study and risks of drawing causal inferences should be highlighted. While immortal time bias could be considered as a potential limitation of this study design, given the short duration between cohort entry and exposure to NMBA therapy, the magnitude of the bias is expected to be limited [57]. In addition, similar times from ICU admission to death were found in both groups. Yet, the risk of immortal time bias should also be considered for several interventions potentially associated with survival—such as prone positioning, ECMO, and corticosteroids—since only patients who survived long enough to receive these interventions were analyzed. Second, the analyzed dataset did not provide any information on the type of NMBA, doses, or adequacy of the block achieved; hence, we were unable to extrapolate the appropriateness of their clinical use. In addition, the time of commencement of NMBA treatment was not recorded; thus, although we included patients who received NMBAs up to 3 days, and we explored different treatment regimens in sensitivity analyses, potential discrepancy in the clinically indicated 2-day full course of NMBA treatment [15, 16] should be considered when interpreting the results. Third, a proportion of the studied population was admitted to the ICU early during the pandemic. Consequently, potential logistical limitations related to managing critically ill patients treated in newly developed and understaffed ICUs, due to shortages in ICU beds or healthcare providers, must be considered. Fourth, as shown in Fig. 4, residual discrepancy for Asia likely persisted post-matching. Further assessment on the potential reasons for this divergence suggested possible increased mortality in control patients from Asia. This could be related to the specific regional differences in ventilatory practice or application of adjunctive therapies, which should be further explored in future studies. Irrespective, potential random effect related to heterogenous practice among collaborating hospitals should be considered while interpreting our results. Fifth, the voluntary nature of site participation in the study must be emphasized, especially during a pandemic, as data may be skewed toward centers with enough resources to enter data. Lastly, as our observational study acquired data from routine clinical records, missing data could have biased our estimates.

Conclusions

Our results derived by PS-matching analysis suggest that among patients with COVID-19 and moderate-to-severe ARDS, early administration of a short course of NMBAs did not result in improved 90-day in-hospital mortality. In addition, NMBA treatment did not impact ventilator-free days. Thus, the use of NMBAs should be cautiously assessed in this population, pending further studies that could elucidate specific indications for NMBAs in COVID-19.

Availability of data materials

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- ARDS:

-

Acute respiratory distress syndrome

- PaCO2 :

-

Arterial partial pressure of carbon dioxide

- CI:

-

Confidence interval

- COVID-19:

-

Coronavirus disease 2019

- COVID-19–CCC/ECMOCARD:

-

COVID-19 Critical Care Consortium incorporating the ExtraCorporeal Membrane Oxygenation for 2019 novel Coronavirus Acute Respiratory Disease

- HR:

-

Hazard ratio

- ISARIC:

-

International Severe Acute Respiratory and Emerging Infection Consortium

- IMV:

-

Invasive mechanical ventilation

- IQR:

-

Interquartile range

- MAP:

-

Mean arterial pressure

- NMBAs:

-

Neuromuscular blocking agents

- PEEP:

-

Positive end-expiratory pressure

- PS:

-

Propensity score

- PaO2/FiO2 :

-

Ratio between arterial partial pressure of oxygen and inspiratory fraction of oxygen

- SD:

-

Standard deviation

- SARS-CoV-2:

-

Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2

- SPRINT-SARI:

-

Short PeRiod IncideNce sTudy of Severe Acute Respiratory Infection

References

COVID-19 Map-Johns Hopkins Coronavirus Resource Center [Internet]. [cited 2020 Jun 7]. Available from: https://coronavirus.jhu.edu/map.html.

Grasselli G, Zangrillo A, Zanella A, Antonelli M, Cabrini L, Castelli A, et al. Baseline characteristics and outcomes of 1591 patients infected with SARS-CoV-2 admitted to ICUs of the Lombardy Region, Italy. J Am Med Assoc. 2020;323:1574–81.

Guan W, Ni Z, Hu Y, Liang W, Ou C, He J, et al. Clinical characteristics of coronavirus disease 2019 in China. N Engl J Med. 2020;382:1708–20.

Richardson S, Hirsch JS, Narasimhan M, Crawford JM, McGinn T, Davidson KW, et al. Presenting characteristics, comorbidities, and outcomes among 5700 patients hospitalized with COVID-19 in the New York City Area. J Am Med Assoc. 2020;323:E1-8.

Karagiannidis C, Mostert C, Hentschker C, Voshaar T, Malzahn J, Schillinger G, et al. Case characteristics, resource use, and outcomes of 10 021 patients with COVID-19 admitted to 920 German hospitals: an observational study. Lancet Respir Med. 2020;8:583–862.

Zhou F, Yu T, Du R, Fan G, Liu Y, Liu Z, et al. Clinical course and risk factors for mortality of adult inpatients with COVID-19 in Wuhan, China: a retrospective cohort study. Lancet. 2020;395:1054–62.

Grasselli G, Scaravilli V, Tubiolo D, Russo R, Crimella F, Bichi F, et al. Quality of life and lung function in survivors of extracorporeal membrane oxygenation for acute respiratory distress syndrome. Anesthesiology. 2019;130:572–80.

Wang D, Hu B, Hu C, Zhu F, Liu X, Zhang J, et al. Clinical characteristics of 138 hospitalized patients with 2019 novel coronavirus-infected pneumonia in Wuhan, China. JAMA. 2020;323:1061–9.

Lim ZJ, Subramaniam A, Reddy MP, Blecher G, Kadam U, Afroz A, et al. Case fatality rates for patients with COVID-19 requiring invasive mechanical ventilation. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2021;203:54–66.

Angus DC. Effect of hydrocortisone on mortality and organ support in patients with severe COVID-19 the REMAP-CAP COVID-19 corticosteroid domain randomized clinical trial the members of the REMAP-CAP investigators appear in supplement 2. JAMA. 2020;324:1317–29.

Investigators TR-C. Interleukin-6 receptor antagonists in critically ill patients with Covid-19. [Internet]. Massachusetts Medical Society; 2021 [cited 2021 Sep 13];384:1491–502. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa2100433.

Benzing G. Sedating drugs and neuromuscular blockade during mechanical ventilation. J Am Med Assoc. 1992;267:1775c–1775.

Merriman HM. The techniques used to sedate ventilated patients. Intensive Care Med. 1981;7:217–24. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF01702623.

Bellani G, Laffey JGG, Pham T, Fan E, Brochard L, Esteban A, et al. Epidemiology, patterns of care, and mortality for patients with acute respiratory distress syndrome in intensive care units in 50 countries. JAMA. 2016;315:788–800.

Papazian L, Forel J-M, Gacouin A, Penot-Ragon C, Perrin G, Loundou A, et al. Neuromuscular blockers in early acute respiratory distress syndrome. N Engl J Med. 2010;363:1107–16. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa1005372.

Early Neuromuscular Blockade in the Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome. N Engl J Med [Internet]. Massachusetts Medical Society; 2019 [cited 2020 Dec 25];380:1997–2008. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1056/nejmoa1901686.

Cummings MJ, Baldwin MR, Abrams D, Jacobson SD, Meyer BJ, Balough EM, et al. Epidemiology, clinical course, and outcomes of critically ill adults with COVID-19 in New York City: a prospective cohort study. Lancet. 2020;395:1763–70.

Ferrando C, Suarez-Sipmann F, Mellado-Artigas R, Hernández M, Gea A, Arruti E, et al. Clinical features, ventilatory management, and outcome of ARDS caused by COVID-19 are similar to other causes of ARDS. Intensive Care Med. 2020. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00134-020-06192-2.

Ziatkowski-Michaud J, Mazard T, Delignette M-C, Wallet F, Aubrun F, Dziadzko M. Neuromuscular monitoring and neuromuscular blocking agent shortages when treating critically ill COVID-19 patients: a multicentre retrospective analysis. Br J Anaesth. 2021;127:e73–5.

Courcelle R, Gaudry S, Serck N, Blonz G, Lascarrou JB, Grimaldi D, et al. Neuromuscular blocking agents (NMBA) for COVID-19 acute respiratory distress syndrome: a multicenter observational study. Crit Care BioMed Central. 2020. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13054-020-03164-2.

von Elm E, Altman DG, Egger M, Pocock SJ, Gøtzsche PC, Vandenbroucke JP. The strengthening the reporting of observational studies in epidemiology (STROBE) statement: guidelines for reporting observational studies. Lancet (London, England). 2007;370:1453–7.

ECMOCARD [Internet]. [cited 2020 Jun 2]. Available from: https://www.elso.org/COVID19/ECMOCARD.aspx.

Dunning JW, Merson L, Rohde GGU, Gao Z, Semple MG, Tran D, et al. Open source clinical science for emerging infections. Lancet Infect Dis. 2014;14:8–9.

Murthy S. Using research to prepare for outbreaks of severe acute respiratory infection. BMJ Glob Health. 2019;4:e001061.

Rubin DB. Using propensity scores to help design observational studies: application to the tobacco litigation. Health Serv Outcomes Res Methodol. 2001;2:169–88.

Rosenbaum PR, Rubin DB. Constructing a control group using multivariate matched sampling methods that incorporate the propensity score. Am Stat JSTOR. 1985;39:33.

Austin PC. Balance diagnostics for comparing the distribution of baseline covariates between treatment groups in propensity-score matched samples. Stat Med. 2009;28:3083–107.

Hughes RA, Heron J, Sterne JAC, Tilling K. Accounting for missing data in statistical analyses: multiple imputation is not always the answer. Int J Epidemiol. 2019;48:1294–304.

Yehya N, Harhay MO, Curley MAQ, Schoenfeld DA, Reeder RW. Reappraisal of ventilator-free days in critical care research. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2019;200:828–36.

Williamson EJ, Forbes A, White IR. Variance reduction in randomised trials by inverse probability weighting using the propensity score. Stat Med. 2014;33:721.

Arroliga A, Frutos-Vivar F, Hall J, Esteban A, Apezteguía C, Soto L, et al. Use of sedatives and neuromuscular blockers in a cohort of patients receiving mechanical ventilation. Chest. 2005;128:496–506.

Murray MJ, Deblock H, Erstad B, Gray A, Jacobi J, Jordan C, et al. Clinical practice guidelines for sustained neuromuscular blockade in the adult critically ill patient. Crit Care Med. 2016;44:2079–103.

Gainnier M, Roch A, Forel JM, Thirion X, Arnal JM, Donati S, et al. Effect of neuromuscular blocking agents on gas exchange in patients presenting with acute respiratory distress syndrome. Crit Care Med. 2004;32:113–9.

Hua Y, Ou X, Li Q, Zhu T. Neuromuscular blockers in the acute respiratory distress syndrome: a meta-analysis. PLoS ONE. 2020;15:e0227664.

Chang W, Sun Q, Peng F, Xie J, Qiu H, Yang Y. Validation of neuromuscular blocking agent use in acute respiratory distress syndrome: a meta-analysis of randomized trials. Crit Care. 2020;24:1–8.

Ho ATN, Patolia S, Guervilly C. Neuromuscular blockade in acute respiratory distress syndrome: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. J Intensive Care. 2020;8:1–11.

Fan E, Beitler JR, Brochard L, Calfee CS, Ferguson ND, Slutsky AS, et al. COVID-19-associated acute respiratory distress syndrome: is a different approach to management warranted? Lancet Respir Med. 2020;8:816–21.

Gibson PG, Qin L, Puah SH. COVID-19 acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS): clinical features and differences from typical pre-COVID-19 ARDS. Med J Aust. 2020;213:54–6.

Grieco DL, Bongiovanni F, Chen L, Menga LS, Cutuli SL, Pintaudi G, et al. Respiratory physiology of COVID-19-induced respiratory failure compared to ARDS of other etiologies. Crit Care. 2020;24:529.

Gattinoni L, Coppola S, Cressoni M, Busana M, Chiumello D. Covid-19 does not lead to a typical” acute respiratory distress syndrome. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2020;201:1299–300.

Langer T, Brioni M, Guzzardella A, Carlesso E, Cabrini L, Castelli G, et al. Prone position in intubated, mechanically ventilated patients with COVID-19: a multi-centric study of more than 1000 patients. Crit Care. 2021;25:1–11.

Barbaro RP, MacLaren G, Boonstra PS, Iwashyna TJ, Slutsky AS, Fan E, et al. Extracorporeal membrane oxygenation support in COVID-19: an international cohort study of the Extracorporeal Life Support Organization registry. Lancet. 2020;396:1071–8.

Ge H, Pan Q, Zhou Y, Xu P, Zhang L, Zhang J, et al. Lung mechanics of mechanically ventilated patients with covid-19: analytics with high-granularity ventilator waveform data. Front Med. 2020;7:541.

Botta M, Tsonas AM, Pillay J, Boers LS, Algera AG, J Bos LD, et al. Ventilation management and clinical outcomes in invasively ventilated patients with COVID-19 (PRoVENT-COVID): a national, multicentre, observational cohort study. Lancet Respir [Internet]. 2020 [cited 2021 Jan 5]; Available from: www.thelancet.com/respiratoryPublishedonline.

Perez-Nieto OR, Guerrero-Gutiérrez MA, Zamarron-Lopez EI, Deloya-Tomas E, Gasca Aldama JC, Ñamendys-Silva SA. Impact of asynchronies in acute respiratory distress syndrome due to coronavirus disease 2019. Crit Care Explor. 2020;2:e0200.

Chen N, Zhou M, Dong X, Qu J, Gong F, Han Y, et al. Epidemiological and clinical characteristics of 99 cases of 2019 novel coronavirus pneumonia in Wuhan, China: a descriptive study. Lancet. 2020;395:507–13.

Zhou C, Gao C, Xie Y, Xu M. COVID-19 with spontaneous pneumomediastinum. Lancet Infect Dis. 2020;50:510.

Zantah M, Dominguez Castillo E, Townsend R, Dikengil F, Criner GJ. Pneumothorax in COVID-19 disease- incidence and clinical characteristics. Respir Res. 2020;21:236. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12931-020-01504-y.

Guérin C, Reignier J, Richard J-C, Beuret P, Gacouin A, Boulain T, et al. Prone positioning in severe acute respiratory distress syndrome. N Engl J Med. 2013;368:2159–68. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa1214103.

Coppo A, Bellani G, Winterton D, Di Pierro M, Soria A, Faverio P, et al. Feasibility and physiological effects of prone positioning in non-intubated patients with acute respiratory failure due to COVID-19 (PRON-COVID): a prospective cohort study. Lancet Respir Med. 2020;8:765–74.

Papazian L, Aubron C, Brochard L, Chiche JD, Combes A, Dreyfuss D, et al. Formal guidelines: management of acute respiratory distress syndrome. Ann Intensive Care. 2019. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13613-019-0540-9.

Schmidt M, Hajage D, Lebreton G, Monsel A, Voiriot G, Levy D, et al. Extracorporeal membrane oxygenation for severe acute respiratory distress syndrome associated with COVID-19: a retrospective cohort study. Lancet Respir Med [Internet]. Lancet Publishing Group; 2020 [cited 2020 Sep 26]; Available from: /pmc/articles/PMC7426089/?report=abstract.

Sottile PD, Kiser TH, Burnham EL, Ho PM, Allen RR, Vandivier RW, et al. An observational study of the efficacy of cisatracurium compared with vecuronium in patients with or at risk for acute respiratory distress syndrome. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2018. https://doi.org/10.1164/rccm.201706-1132OC.

Mao L, Jin H, Wang M, Hu Y, Chen S, He Q, et al. Neurologic manifestations of hospitalized patients with coronavirus disease 2019 in Wuhan, China. JAMA Neurol Am Med Assoc. 2020;77:683–90.

Pérez Álvarez ÁI, Suárez Cuervo C, Fernández MS. SARS-CoV-2 infection associated with diplopia and anti-acetylcholine receptor antibodies. Neurol (English Ed). 2020;35:264–5.

Restivo DA, Centonze D, Alesina A, Marchese-Ragona R. Myasthenia gravis associated with SARS-CoV-2 infection. Ann Intern Med. 2020. https://doi.org/10.7326/L20-0845.

Lévesque LE, Hanley JA, Kezouh A, Suissa S. Problem of immortal time bias in cohort studies: example using statins for preventing progression of diabetes. BMJ. 2010;340:907–11.

Acknowledgements

We recognize the crucial importance of the ISARIC and SPRINT-SARI networks in developing and expanding the global COVID-19 Critical Care Consortium. We thank the generous support we received from the Extracorporeal Life Support Organization (ELSO) and the International ECMO Network (ECMONet). We greatly acknowledge Adrian Barnett for his invaluable contribution to the analysis plan and statistical insights. We greatly acknowledge Gabriele Fior (University of Milan) for his input and contribution to the critical revision of the manuscript. We owe Li Wenliang, MD, from the Wuhan Central Hospital, an eternal debt of gratitude for reminding the world that doctors should never be censored during a pandemic. Finally, we acknowledge all members of the COVID-19 Critical Care Consortium and various collaborators as reported in the Additional file 1: Appendix.

Funding

The University of Queensland; The Wesley Medical Research; The Prince Charles Hospital Foundation; Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation c/o Open Access—Grant number INV-034765; The Health Research Board of Ireland; Gianluigi Li Bassi is a recipient of the BITRECS fellowship; the BITRECS” project has received funding from the European Unions Horizon 2020 research and innovation program under the Marie Skłodowska-Curie grant agreement no. 754550 and from the La Caixa” Foundation (ID 100010434), under the agreement LCF/PR/GN18/50310006. Finally, Carol Hodgson is funded by the National Health and Medical Research Council Grant.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Consortia

Contributions

GLB, JF, and JYS conceived of the study, participated in its design and coordination, and helped to draft the manuscript; KG and HD participated in the design of the study and coordination, conducted the statistical analysis, and helped to draft the manuscript; NW performed the statistical analysis and helped to draft the manuscript; AC, SS, SH, SF, JGL, EF, JoF, RB, DB, AB, DC, AA, ME, GG, CH, SH, CL, EM, LM, SM, AN, MO, PP, AT, and PY participated in collection of data and reviewed the initial draft of the manuscript; MP participated in collection of data, helped in the statistical analysis and reviewed the initial draft of the manuscript, Kristen Gibbons contributed to statistical analysis. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Participating hospitals obtained local ethics committee approval, and a waiver of informed consent was granted in all cases.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

A/Prof Li Bassi received research support from Fisher & Paykel outside the submitted work. Prof. Dalton consults with Innovative ECMO Concepts, Abiomed and Instrumentation Labs, which does not affect the current work. Prof. Brodie receives research support from ALung Technologies, and he has been on the medical advisory boards for Baxter, Abiomed, Xenios, and Hemovent. A/Prof Fan reports personal fees from ALung Technologies, Baxter, Fresenius Medical Care, Getinge, and MC3 Cardiopulmonary outside the submitted work. Prof. Laffey reports consulting fees from Baxter and Cala Medical, both outside the submitted work. Prof. Nichol is supported by a Health Research Board of Ireland Award (CTN-2014-012). Prof. Fraser receives research support from Fisher & Paykel outside the submitted work. Prof. Grasselli reports personal fees from Draeger Medical, Biotest, Getinge, Fisher & Paykel, and MSD outside the submitted work.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1

. Appendix.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Li Bassi, G., Gibbons, K., Suen, J.Y. et al. Early short course of neuromuscular blocking agents in patients with COVID-19 ARDS: a propensity score analysis. Crit Care 26, 141 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13054-022-03983-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13054-022-03983-5