Abstract

Background

Hospitalized patients with COVID-19 admitted to the intensive care unit (ICU) and requiring mechanical ventilation are at risk of ventilator-associated bacterial infections secondary to SARS-CoV-2 infection. Our study aimed to investigate clinical features of Staphylococcus aureus ventilator-associated pneumonia (SA-VAP) and, if bronchoalveolar lavage samples were available, lung bacterial community features in ICU patients with or without COVID-19.

Methods

We prospectively included hospitalized patients with COVID-19 across two medical ICUs of the Fondazione Policlinico Universitario A. Gemelli IRCCS (Rome, Italy), who developed SA-VAP between 20 March 2020 and 30 October 2020 (thereafter referred to as cases). After 1:2 matching based on the simplified acute physiology score II (SAPS II) and the sequential organ failure assessment (SOFA) score, cases were compared with SA-VAP patients without COVID-19 (controls). Clinical, microbiological, and lung microbiota data were analyzed.

Results

We studied two groups of patients (40 COVID-19 and 80 non-COVID-19). COVID-19 patients had a higher rate of late-onset (87.5% versus 63.8%; p = 0.01), methicillin-resistant (65.0% vs 27.5%; p < 0.01) or bacteremic (47.5% vs 6.3%; p < 0.01) infections compared with non-COVID-19 patients. No statistically significant differences between the patient groups were observed in ICU mortality (p = 0.12), clinical cure (p = 0.20) and microbiological eradication (p = 0.31). On multivariable logistic regression analysis, SAPS II and initial inappropriate antimicrobial therapy were independently associated with ICU mortality. Then, lung microbiota characterization in 10 COVID-19 and 16 non-COVID-19 patients revealed that the overall microbial community composition was significantly different between the patient groups (unweighted UniFrac distance, R2 0.15349; p < 0.01). Species diversity was lower in COVID-19 than in non COVID-19 patients (94.4 ± 44.9 vs 152.5 ± 41.8; p < 0.01). Interestingly, we found that S. aureus (log2 fold change, 29.5), Streptococcus anginosus subspecies anginosus (log2 fold change, 24.9), and Olsenella (log2 fold change, 25.7) were significantly enriched in the COVID-19 group compared to the non–COVID-19 group of SA-VAP patients.

Conclusions

In our study population, COVID-19 seemed to significantly affect microbiological and clinical features of SA-VAP as well as to be associated with a peculiar lung microbiota composition.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Since its first detection in China, the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2)-caused pneumonia, known as coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19), has become an unprecedented global pandemic [1]. Although many SARS-CoV-2 infected individuals undergo a mild disease [2], a significant proportion of hospitalized patients require admission to the intensive care unit (ICU) [3]. In this setting [4], mechanical ventilation (MV) is commonly used to provide supportive care [5], especially in patients with acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS), which is a well-established feature of COVID-19 pathophysiology [6]. While up to 50% of ventilated patients do not survive SARS-CoV-2 infection [7], ICU patients have a greater risk of secondary infection or superinfection by bacterial pathogens compared to patients in mixed ward/ICU settings [8]. It is plausible that SARS-CoV-2 infection impairs pulmonary immune responses against bacteria [9] or alters the dynamics of inter-microbial interactions [10], thereby leading to enhanced growth of pathogenic species. It is also plausible that co-infection exacerbates the lung damage triggered by SARS-CoV-2 and, then, facilitate pathogen’s systemic dissemination [7]. To date it is unclear whether specific co-infecting pathogens are associated with poor outcomes [11], as well as they correlate with the microbial community in the lung of patients suffering from SARS-CoV-2 infection [12]. A recent study investigating the lung-tissue microbiota characteristics of 20 deceased patients with COVID-19 (80% were mechanically ventilated) found a bacterial community enriched with Acinetobacter species [13], which include carbapenem-resistant A. baumannii [14]. Concomitantly, Kreitmann et al. reported that Staphylococcus aureus (SA) accounted for ~ 70% of bacteria isolated from early sampled lower respiratory tract of COVID-19 patients, who required mechanical ventilation for ARDS [15]. No significant difference in day-28 mortality was observed according to the presence of co-infection, and this finding was consistent with the receipt of appropriate antibiotic treatment (all SA isolates were methicillin susceptible) in co-infected patients [15]. Similarly, in critically ill influenza patients superinfected by bacterial pathogens, SA was the most common pathogen [16], whereas much less virulence to SA isolates might be required for bacterial superinfection in cases of preceding influenza infection [17]. Thus, any colonizing SA isolate may induce bacterial superinfection, suggesting that an altered balance between commensals and potential pathogens in a virus-conditioned lung microbiota may contribute to aggravate SARS-CoV-2-induced pneumonia.

The aim of this study was to investigate clinical features of SA ventilator-associated pneumonia (SA-VAP) in ICU patients with or without COVID-19. We also investigated the lung microbiota of patients for whom lower respiratory tract samples were available to identify bacterial community features related to COVID-19.

Methods

Study setting and design

This observational study prospectively included hospitalized patients with COVID-19 across two medical ICUs of the Fondazione Policlinico Universitario A. Gemelli IRCCS (Rome, Italy), who developed SA-VAP between 20 March 2020 and 30 October 2020 (thereafter referred to as cases). A control group of SA-VAP patients admitted to the same study sites between the calendar years 2017 and 2019 was also included and used as a historical non–COVID-19 comparator group (in this case prospectively collected data were retrospectively analyzed). For both groups, electronic patient records and microbiology laboratory data were used to identify patients and to retrieve clinical data (e.g., presence of one or more comorbidities), microbiological results (i.e., from cultures of bronchoalveolar lavage [BAL] fluid or other relevant samples), receipt and/or type of antimicrobial treatment(s), and outcomes. Following identification, patients from COVID-19 group were 1:2 matched with those from non–COVID-19 group (control patients), based on the Simplified Acute Physiology Score II (SAPS II) [18] (within 5 points at ICU admission), and the Sequential Organ Failure Assessment (SOFA) score [19] (within 2 points at SA-VAP diagnosis). In cases of multiple possible controls, choice fell on those patients who shared closest SAPS II and SOFA score values. During case–control matching, investigators were blinded to cases’ outcomes.

The study was performed in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Fondazione Policlinico A. Gemelli IRCCS (reference number 23703/19). A written informed consent or proxy consent was obtained according to committee recommendations.

Definitions and outcomes

Acute kidney injury, ARDS, septic shock, or VAP were defined according to previously reported criteria [20,21,22,23]. The SA-VAP was defined as bacteremic when the diagnosis of SA-VAP coincided with S. aureus isolation in at least one blood culture in the absence of other specified source of bacteremia [24]. The primary outcome was the mortality in the ICU, whereas secondary outcomes were the clinical cure, microbiological cure, and in-hospital mortality. Clinical cure of SA-VAP was defined as the complete resolution of all signs and symptoms of infection by the end of targeted therapy (i.e., appropriate antimicrobial therapy), including no progression of any previous chest-radiography abnormalities. Microbiological cure was defined as the lack of SA growth in cultures from subsequently collected respiratory tract and/or blood samples. Empirical antimicrobial therapy, called inappropriate initial antimicrobial treatment (IIAT), consisted into administering an antimicrobial agent against which the patient’s SA isolate was not susceptible (see above). When judgements were discordant (about 2% of patients), the reviewers reassessed the data and reached a consensus decision (see Additional file 1: Figure S1 e-diagram).

Microbiology laboratory testing

Microbiota characterization

We characterized the microbiota of BAL fluid samples collected from a subset of SA-VAP patients in both COVID-19 and non–COVID-19 groups. All samples were stored at − 80 °C until processing, which only for samples from COVID-19 patients was performed in a biosafety level 3 cabinet. Total DNA was extracted in a strictly controlled separate and aseptic laboratory workplace. Briefly, 5 ml of each sample was centrifuged, and the resulting pellet was carefully resuspended in sterile phosphate-buffered saline. This suspension was used to extract DNA with the DANAGENE MICROBIOME Saliva DNA kit (DanaGen-BioTed S.L., Barcelona, Spain) according to manufacturer’s instructions. The extracted DNA from each sample was checked for quality by agarose gel electrophoresis and for concentration by the Qubit™ 4.0 fluorometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Rodano, Italy) measurement using the Qubit dsDNA HS (High Sensitivity) Assay kit (Life Technologies, Monza, Italy). For each sample, the V3‒V4 hypervariable regions of the 16S rRNA gene was amplified using forward and reverse primers that contained the sequences 5′-TCGTCGGCAGCGTCAGATGTGTATAAGAGACAGCCTACGGGNGGCWGCAG3′ and 5′-TCTCGTGGGCTCGGAGATGTGTATAAGAGACAGGACTACHVGGGTATCTAATCC-3′, respectively [25]. The resulting amplicons were purified using Agencourt AMPure XP beads (Beckman Coulter, Milan, Italy) and then barcoded using the Nextera XT Index kit (Illumina, San Diego, CA, USA). Indexed amplicons were diluted to reach relative equimolar concentrations with one another, and the resulting library was sequenced on a MiSeq® instrument (Illumina) using a 2 × 300 paired-end configuration according to manufacturer’s recommendations. To increase the base-diversity degree, we added an internal control (PhiX v3; Illumina) to the library as previously described [26]. Sequencing reads have been submitted to the NCBI Sequence Read Archive (PRJNA693784). After demultiplexing of raw sequencing reads, FastQ sequences were analyzed according to the QIIME 2 (Quantitative Insights into Microbial Ecology 2) bioinformatics pipeline [27]. Briefly, FastQ sequences were trimmed to remove primers and barcodes, and were then quality filtered (4202769 in total; 1470182 and 2640530 reads from COVID-19 and non–COVID-19 patient samples, respectively). We processed the sterile saline used for sample collection as an extraction and sequencing control, which yielded median 151901 reads per sample. Using the DADA2 algorithm [28], removal of chimeras led to obtain amplicon sequence variants (ASVs), which underwent a taxonomic annotation via a pre-fitted scikit-learn classifier based on SILVA 132 reference database [https://www.scikit-learn.org/stable/]. Finally, we removed sequences from mitochondrial DNA or sequences from microbial taxa with less than 0.01% representability [29].

Statistical analyses

Clinical data analysis was performed using MedCalc Statistical Software version 16.4.3 (MedCalc, Ostend, Belgium), whereas data were graphed using GraphPad Prism version 6.0 (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA). Continuous data were presented as median (interquartile range [IQR]), whereas categorical data were presented as counts and proportions. Differences between groups for continuous data were assessed using either Student’s t-test (normally distributed) or Mann–Whitney U-test (non-normally distributed), whereas those for categorical data were assessed using the chi-square test or Fisher’s exact test as appropriate. Odds ratios and 95% confidence intervals were calculated. Variables with a P value < 0.1 in univariable analysis were included in multivariable analyses, which were conducted using stepwise logistic regression. Microbial community data analysis was performed in R studio version 4.0.2 (https://www.rstudio.com/) using the phyloseq package [30]. For each sample, alpha diversity was determined by calculating diversity indices (number of observed species, Shannon, the Simpson’s inverse, and the Pielou’s species evenness) at a rarefaction depth of 105,851 sequences, and significant differences between groups were assessed using the Wilcoxon nonparametric test. To assess compositional (dis)similarity between samples, beta diversity was determined by calculating the unweighted UniFrac distance and was visualized as a principal coordinates analysis (PCoA) plot [31], and significant differences between groups were assessed using PERMANOVA. Relative abundances of microbial community members between groups were also calculated, whereas the analysis of differentially abundant taxa was conducted using the DESeq2 package [32]. In all analyses, a P value < 0.05 was set as the statistical significance threshold.

Results

Characteristics of patients who developed SA-VAP in the ICU

During the study period, 40 (43.5%) of 92 VAPs were due to SA and thus selected for the analysis (Additional file 1: Figure S1 e-diagram). COVID-19 patients with SA-VAP (n = 40) were compared with non–COVID-19 patients with SA-VAP (n = 80), who were used as controls (Table 1). At the time of SA-VAP diagnosis, we did not observe significant differences between patient groups in terms of demographics or main comorbidities. Furthermore, rate of septic shock, acute kidney injury requiring renal replacement therapy, duration of ICU stay, and use of mechanical ventilation before SA-VAP were similar in both groups. Regarding SA-VAP features, COVID-19 patients were more likely to have a late-onset infection (35/40 [87.5%] vs. 51/80[63.8%]; P = 0.01), methicillin-resistant infection (26/40 [65%] vs. 22/80 [27.5%]; P < 0.01), or bacteremic infection (19/40 [47.5%] vs. 5/80 [6.3%]; P < 0.01) than non–COVID-19 patients (see also Fig. 1a) (see also Additional file 2: e-Table S1). Regarding antistaphylococcal antimicrobial agents, linezolid was most frequently used to treat COVID-19 patients (24/40 [60%] vs. 8/80 [10%]; P < 0.01), whereas other (non-oxacillin or non-vancomycin) agents to treat non–COVID-19 patients (2/40 [5%] vs. 34/80 [42.5%]; P < 0.01). Interestingly, no statistically significant differences between COVID-19 and non–COVID-19 groups were found regarding the receipt of IIAT or the duration of antimicrobial treatment (Table 1).

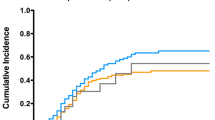

a Microbiological and clinical features of SA VAP in COVID-19 patients and controls. b Kaplan–Meier curve showing the impact of IIAT (black line) on ICU mortality. SA: Staphylococcus aureus; BSI: bloodstream infection; MRSA: methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus; Micro: microbiological; VAP: ventilator-associated pneumonia; IIAT: initial inadequate antibiotic therapy; IAAT: initial adequate antibiotic therapy

Outcomes and predictors of ICU mortality

Despite being higher among COVID-19 patients, ICU mortality did not significantly differ between COVID-19 or non–COVID-19 groups (35% vs. 20%, P = 0.12) (Table 1). Similarly, no differences between groups were observed regarding clinical cure and microbiological eradication of SA-VAP (see also Fig. 1a). Comparing alive (n = 90) or deceased (n = 30) patients on univariate analysis (Table 2) showed that age (P = 0.01), SAPS II (P < 0.01), and the SOFA score (P = 0.06) were associated with higher risk of death. Similarly, neoplasm (P = 0.06), COVID-19 (P = 0.08), bacteremic infection (P = 0.01), methicillin-resistant infection (P = 0.01), and IIAT (P ≤ 0.01) were more likely to occur in patients who died. Furthermore, deceased patients were more likely to receive linezolid treatment (P = 0.02) than alive patients were, whereas oxacillin treatment was associated with lower risk of death (P = 0.01). However, on multivariable logistic regression analysis (Table 2), SAPS II (adjusted odds ratio [OR], 1.08; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.03–1.14; P < 0.01) and IIAT (adjusted OR, 4.63, 95% CI, 1.56–13.7; P < 0.01) were found to be independently associated with ICU mortality. The multivariable Cox-regression model confirmed that IIAT significantly increased the risk of ICU mortality (hazard ratio [HR], 3.5; 95% CI, 1.62–7.72), which was consistent with the Kaplan–Meier survival curve analysis results (P < 0.01) shown in Fig. 1b.

SA-VAP related lung microbiota profiles of COVID-19 or non–COVID-19 patients

Our sequencing strategy of BAL samples obtained from COVID-19 (n = 10) or non–COVID-19 (n = 16) patients provided 3,928,074 sequences in total (ranging from 105,857 to 202,048 sequences per sample), which were classified in 542 ASVs representing 11 bacterial phyla. The most prominent phyla were (in alphabetic order) Actinobacteria, Bacteroidetes, Firmicutes, Fusobacteria, Proteobacteria, and Tenericutes, together accounting for 99.9% of all sequences. Although previous antimicrobial prescriptions (90% vs. 100%, p = 0.81) and mechanical ventilation days (9 days [6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19] in COVID pts vs 7.5 days [4–14.5] in non-COVID patients; p = 0.46) were similar in the two groups, we observed that the overall composition of the lung microbiota in COVID-19 patients was significantly different from that in non–COVID-19 patients (unweighted UniFrac distance, R2 0.15349, P = 0.004) (Fig. 2). However, the UniFrac-derived PCoA plot showed overlapping between the two microbial communities, indicating that samples of patient groups’ communities shared features that may account for clustering on different spatial levels. According to observed species, diversity was lower in patients from the COVID-19 group compared to patients from the non–COVID-19 group (94.4 ± 44.9 vs. 152.5 ± 41.8; P = 0.001) (Fig. 2). Conversely, no significant differences were observed in the Shannon (P = 0.421), Simpson’s inverse (P = 0.979), or Pielou's species evenness (P = 0.938) indices. We compared the taxa at phylum and genus level between COVID-19 and non–COVID-19 groups (Fig. 2). At phylum level, Tenericutes were relatively more abundant in patients with COVID-19 (2.8% vs. 1.7%), whereas Actinobacteria were present only in patients with COVID-19 (6.7%). Conversely, Fusobacteria and Proteobacteria were relatively less abundant in COVID-19 patients (1.0% vs. 2.7% and 16.8% vs. 24.9%, respectively). In both groups, relative abundances of Bacteroidetes and Firmicutes were similar (around 45.0%). At genus level, Porphyromonas (Bacteroidetes) and Prevotella 7 (Bacteroidetes) were relatively more abundant in COVID-19 patients (3.5% and 7.0% vs. 1.1% and 3.4%, respectively). Conversely, Alistipes (Bacteroidetes), Bacteroides (Bacteroidetes), and Fusobacterium (Fusobacteria) were relatively less abundant in COVID-19 patients (2.1%, 7.1%, and 2.3% vs. 1.2%, 3.8%, and 1.0%, respectively). Interestingly, Bifidobacterium (Actinobacteria), Corynebacterium 1 (Actinobacteria), Prevotella 6 (Actinobacteria), Enterococcus (Firmicutes), Lactobacillus (Firmicutes), Peptoniphilus (Firmicutes), Klebsiella (Proteobacteria) (2.0%), and Stenotrophomonas (Proteobacteria) were present only in COVID-19 patients. Conversely, Gemella (Firmicutes), Aggregatibacter (Proteobacteria), Haemophilus (Proteobacteria), and Neisseria (Proteobacteria) were present only in non–COVID-19 patients. We also used DESeq analysis to identify taxa for which the relative abundance was significantly different in patients with or without COVID-19. In addition to Peptoniphilus (log2 fold change, 24.6), Prevotella 7 (log2 fold change, 22.7), and Bifidobacterium dentium (log2 fold change, 21.3), we found that Staphylococcus aureus (log2 fold change, 29.5), Streptococcus anginosus subspecies anginosus (log2 fold change, 24.9), and Olsenella (log2 fold change, 25.7) were significantly enriched in the COVID-19 group compared to the non–COVID-19 group of SA-VAP patients (Fig. 3).

Lung microbiota composition and diversity indices in patients with S. aureus respiratory infection. Alpha diversity (a) and Unweighted Unifrac Beta diversity (b) were analysed on the basis of the dataset normalized to 105,851 reads per sample. The two groups compared were defined by SARS-CoV-2 positive infection. The differences between groups were assessed by Wilcoxon nonparametric test showing a lower alpha diversity in COVID-19 group compared to patients from the non-COVID-19 group (Observed index: 94.4 ± 44.9 vs. 152.5 ± 41.8; P = 0.001). No significant differences were observed in the Shannon (P = 0.421), Simpson’s inverse (P = 0.979), or Pielou's evenness (P = 0.938) indices. Permutational multivariate analysis of variance (PERMANOVA) showed significant differences between the microbial communities of the two groups (R2 0.15349, P = 0.004). Panel C shows the mean of the relative abundances of the 30 more represented genera within the six major phyla that compose the lung bacterial community of COVID-19 and non-COVID-19 groups

Differential abundances between patients with concomitant SARS-CoV-2 and S. aureus respiratory infection and SARS-CoV-2-negative patients with S. aureus infection. The analysis of differentially abundant taxa was assessed using the DESeq2 package. In all analyses, a P value < 0.05 was set as the statistical significance threshold. Positive values of log2 Fold change represent genera significantly more abundant in Covid-19 group

Discussion

We studied clinical features of ICU patients with early or late SA-VAP who were categorized as having (n = 40) or not having (n = 80) COVID-19, which is a well-known predisposing condition to bacterial co-infection or superinfection [8, 33]. Patients without COVID-19 had been hospitalized in the ICU before the end of 2019, the date COVID-19 has become globally pandemic [1]. While COVID-19 or non-COVID-19 patient groups did not significantly differ in terms of ICU mortality (P > 0.05), we found that patients with COVID-19 significantly differed from patients without COVID-19 in terms of clinically relevant SA-VAP features such as a bacteremic (P < 0.01) or a methicillin-resistant (P < 0.01) infection. We therefore tried to relate these findings to the lung microbial community features that were investigated in subgroups of COVID-19 (n = 10) or non-COVID-19 (n = 16) patients.

A blood culture results’ evaluation study in COVID-19 patients presenting to New York city (NYC) hospitals revealed that SA was the second (after Escherichia coli) most common cause of bacteremia among COVID-19 patients [34]. In another recent study [35], SA has been the most detected respiratory pathogen in SARS-CoV-2 positive (7/10; 70%) compared with SARS-CoV-2 negative (18/53; 34%) patients. Again, in a bacterial infections’ analysis in 74 hospitalized patients with COVID-19 [36], 59.5% (44/74) of patients acquired superinfections, with 11 (25.0%) of 44 being VAP (caused by SA in 4/11 [36.4%]) and 16 (36.4%) of 44 being bacteremia (caused by coagulase-negative staphylococci in 7/16 [43.8%]). While 56.8% (25/44) of these superinfections occurred in ICU patients and caused worse outcomes [36], it seemed that bacteremia did not complicate SA-VAP in that study. Conversely, in a SA-bacteremia series in COVID-19 patients from two NYC hospitals, Cusumano et al. [37] identified pneumonia in 8 (19.0%) of 42 cases as a source of infection, with 5 (26.3%) of 19 patients surviving at 14 days from the first positive blood culture.

In our study, bacteremic infection was significantly more frequent in patients with than in patients without COVID-19. Several factors in COVID-19 patients may account for this finding, such as complex immune dysregulation [38], administration of immunomodulatory drugs (e.g. corticosteroids), long durations of ICU stay and MV prior to infection onset. Our data was consistent with the observed prevalence of nosocomial bloodstream infections in ICU patients [39], but it was in contrast with that reported previously [34, 40, 41]. Very recently, the OUTCOMEREA network describing clinical and epidemiological features of COVID-19 patients observed that these patients were significantly more likely to develop late-onset (> 7 days) ICU-acquired bloodstream infections compared to non-COVID-19 patients [42]. Furthermore, COVID-19 patients were found to develop more VAP than patients without COVID-19 despite sharing a similar pulmonary microbiota [43]. Until recently (i.e., in pre–COVID-19 era), bacteremic SA pneumonia was considered as relatively uncommon despite being associated with high mortality rates [39]. Among 98 pneumonia cases, 56 due to methicillin-susceptible SA (MSSA) and 42 due to methicillin-resistant SA (MRSA), studied by De la Calle et al. in 2016 [24], 7.1% (7/98) of cases were bacteremic. In another study [39] conducted in 2006 on patients from nine European countries’ ICUs, bacteremia (caused by MRSA or A. baumannii) accounted for 70 (14.6%) of 479 culture-documented cases of nosocomial pneumonia (465 of which were VAP). MRSA infection was an independent risk factor for the development of bacteremia, and ICU mortality was significantly higher in bacteremic (57.1%) than in non-bacteremic patients (33.0%; P < 0.001). Said that, it is noteworthy that, in our study, rates of bacteremic or methicillin-resistant infections were significantly higher in COVID-19 (47.5% and 65.0%, respectively) than in non-COVID-19 (6.3% and 27.5%, respectively) patients (P < 0.01, for both comparisons). Finally, taken together, these findings are consistent with the results from a 18 studies’ meta-analysis on 8,249 samples from COVID-19 patients [44]. The analysis showed that SA accounted for 25.6% (95% CI 15.6–39.0) of microbial pathogen/COVID-19 coinfections whereas MRSA accounted for 53.9% (95% CI, 24.5–80.9) of SA/COVID-19 coinfections.

Although the role of synergic interactions between SARS-CoV-2 and co-infecting bacteria remains unclear [11], changes in the respiratory tract microbiota (i.e., a dysbiosis status) of VAP patients [45] may reduce the resistance to colonization by potentially pathogenic bacteria [7], including antibiotic-resistant bacteria such as MRSA [46]. It is also plausible that SARS-CoV-2 infection uncovers bacterial receptors on epithelial lung cells, thereby favoring bacterial attachment, growth, and dissemination, and then increasing the risk of bloodstream infection and sepsis [7]. On the other hand, extensive antibiotic treatments in COVID-19 patients [47] may perturb gut homeostasis, allowing bacterial pathogens to cause pneumonia or other invasive infections [48]. Consistent with a significantly altered gut microbiota of COVID-19 patients compared to healthy controls [49], our 16S rRNA gene sequencing data show that the lung bacterial community of patients with COVID-19 was different from that of patients without COVID-19 (P = 0.004). Interestingly, Olsenella and Streptococcus anginosus, which normally inhabit the oropharynx forming biofilm to enhance bacterial adherence and thriving [50], were among the taxa significantly enriched in the COVID-19 lung microbiota together with SA. Thus, co-dominance of SA with oropharyngeal bacteria in the lung microbiota from COVID-19 patients may result from viral-induced dysbiosis and/or dysregulated immune responses [9] that, in turn, modify the interaction with other bacterial or host cells [51]. Consequently, the route by which SA-VAP progresses may differ in COVID-19 from in non-COVID-19 patients, supporting higher rates of bacteremia or other clinical features (i.e., methicillin-resistant infection) in COVID-19 patients than in non-COVID-19 patients observed by us. Otherwise, the hypothesis that hypervirulence [52] or good-fitness [17] attributes drove SA to become dominant in the lung of COVID-19 patients cannot be excluded. In our population, it was difficult to dissect changes in the lung microbiota in COVID-19 versus non–COVID-19 patients that might have occurred following the challenge with SARS-CoV-2 from changes that might have reflected differing antimicrobial susceptibility or evolving characteristics of the microbial community in the lung of patients during the study periods. However, we tried to overcome this study limitation by checking the two patient groups for potential differences in prior antimicrobial use or in duration of mechanical ventilation, which both are known to perturb the respiratory tract community and to affect the vulnerability to pneumonia in ICU patients.

In this study, ICU mortality was not statistically different between patients with and without COVID-19. Conversely, data in critically ill patients with influenza showed that the presence of coinfections, particularly SA coinfection, was an independent risk factor for mortality [53, 54]. In our patients, common profiles of clinical severity and management were found to be associated with ICU mortality, while the potential of decreased lung bacterial diversity to influence ICU mortality in COVID-19 patients was not assessed..

The present study had some limitations. First, its monocentric design could limit the applicability of our findings to non-ICU settings or to other centers. Second, the sample size was relatively small, the ratio of matched cases/controls was not 1:1 and the controls were selected during a different period (three-year period before cases). Third, the role of the immune dysregulation status (e.g. laboratory data) and of the administration of immunomodulatory drugs (e.g. corticosteroids) in the study group was not investigated, although both factors could have influenced clinical and microbiological findings. Finally, SA-VAP diagnosis was based on both tracheal aspirate and bronchoalveolar lavage samples, because the latter samples were not systematically obtained due to high risk of aerosol generation.

Conclusions

Bacterial coinfections/superinfections represent a challenging issue in critically ill COVID-19 patients. Late-onset and methicillin-resistant SA-VAP typically occur in these patients, and are significantly associated with bloodstream dissemination. SARS-CoV-2 lung dysbiosis may explain such peculiar features, but ICU mortality remains mainly driven by the severity of clinical conditions or the prompt initiation of effective antibiotic therapy.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- COVID-19:

-

Coronavirus disease 2019

- SA:

-

Staphylococcus aureus

- VAP:

-

Ventilator-associated pneumonia

- ICU:

-

Intensive care unit

- BAL:

-

Bronchoalveolar lavage

- SAPSII:

-

Simplified Acute Physiology Score II

- SOFA:

-

Sequential Organ Failure Assessment

- SARS-CoV-2:

-

Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2

- MV:

-

Mechanical ventilation

- ARDS:

-

Acute respiratory distress syndrome

- IIAT:

-

Inappropriate initial antimicrobial treatment

- dsDNA:

-

Double-stranded Deoxyribonucleic acid

- HS:

-

High sensitivity

- rRNA:

-

Ribosomal ribonucleic acid

- NCBI:

-

National Center for Biotechnology Information

- QIIME 2:

-

Quantitative insights into microbial ecology 2

- DADA:

-

Divisive Amplicon Denoising Algorithm

- ASVs:

-

Amplicon sequence variants

- IQR:

-

Interquartile range

- OR:

-

Odds ratio

- CI:

-

Confidence interval

- PCoA:

-

Principal coordinates analysis

- PERMANOVA:

-

Permutational multivariate analysis of variance

- HR:

-

Hazard ratio

- NYC:

-

New York city

- MSSA:

-

Methicillin-susceptible Staphylococcus aureus

- MRSA:

-

Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus

References

World Health Organization. COVID-19 Weekly Epidemiological Update 22. World Heal Organ. 2021;1–3. Available from: https://www.who.int/docs/default-source/coronaviruse/situation-reports/weekly_epidemiological_update_22.pdf.

Rodriguez-Morales AJ, Cardona-Ospina JA, Gutiérrez-Ocampo E, Villamizar-Peña R, Holguin-Rivera Y, Escalera-Antezana JP, et al. Clinical, laboratory and imaging features of COVID-19: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Travel Med Infect Dis. 2020;34:101623. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tmaid.2020.101623.

Kotfis K, Williams Roberson S, Wilson JE, Dabrowski W, Pun BT, Ely EW. COVID-19: ICU delirium management during SARS-CoV-2 pandemic. Crit Care. 2020;24:176. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13054-020-02882-x.

Alhazzani W, Møller MH, Arabi YM, Loeb M, Gong MN, Fan E, et al. Surviving sepsis campaign: guidelines on the management of critically ill adults with coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19). Intensive Care Med. 2020;46:854–87. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00134-020-06022-5.

Grasselli G, Tonetti T, Protti A, Langer T, Girardis M, Bellani G, et al. Pathophysiology of COVID-19-associated acute respiratory distress syndrome: a multicentre prospective observational study. Lancet Respir Med. 2020;8(12):1201–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2213-2600(20)30370-2.

Grieco DL, Bongiovanni F, Chen L, Menga LS, Cutuli SL, Pintaudi G, et al. Respiratory physiology of COVID-19-induced respiratory failure compared to ARDS of other etiologies. Crit Care. 2020;24:1–11. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13054-020-03253-2.

Bengoechea JA, Bamford CG. SARS-CoV-2, bacterial co-infections, and AMR: the deadly trio in COVID-19? EMBO Mol Med. 2020;12:e12560. https://doi.org/10.15252/emmm.202012560.

Lansbury L, Lim B, Baskaran V, Lim WS. Co-infections in people with COVID-19: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Infect. 2020;81:266–75. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jinf.2020.05.046.

Manohar P, Loh B, Nachimuthu R, Hua X, Welburn SC, Leptihn S. Secondary Bacterial Infections in Patients With Viral Pneumonia. Front Med. 2020;7:420. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmed.2020.00420.

Hanada S, Pirzadeh M, Carver KY, Deng JC. Respiratory viral infection-induced microbiome alterations and secondary bacterial pneumonia. Front Immunol. 2018;9:2640. https://doi.org/10.3389/fimmu.2018.02640.

Vaillancourt M, Jorth P. The Unrecognized Threat of Secondary Bacterial Infections with COVID-19. MBio. 2020;11:e01806-e1820. https://doi.org/10.1128/mBio.01806-20.

Shen Z, Xiao Y, Kang L, Ma W, Shi L, Zhang L, et al. Genomic diversity of severe acute respiratory syndrome-coronavirus 2 in patients with coronavirus disease 2019. Clin Infect Dis. 2020;71:713–20. https://doi.org/10.1093/cid/ciaa203.

Fan J, Li X, Gao Y, Zhou J, Wang S, Huang B, et al. The lung tissue microbiota features of 20 deceased patients with COVID-19. J Infect. 2020;81:e64–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jinf.2020.06.047.

Zheng Y, Wan Y, Zhou L, Ye M, Liu S, Xu C, et al. Risk factors and mortality of patients with nosocomial carbapenem-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii pneumonia. Am J Infect Control. 2013;41:e59-63. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajic.2013.01.006.

Kreitmann L, Monard C, Dauwalder O, Simon M, Argaud L. Early bacterial co-infection in ARDS related to COVID-19. Intensive Care Med. 2020;46:1787–9. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00134-020-06165-5.

McCullers JA. The co-pathogenesis of influenza viruses with bacteria in the lung. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2014;12:252–62. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrmicro3231.

Deinhardt-Emmer S, Haupt KF, Garcia-Moreno M, Geraci J, Forstner C, Pletz M, et al. Staphylococcus aureus pneumonia: preceding influenza infection paves the way for low-virulent strains. Toxins. 2019;11:734. https://doi.org/10.3390/toxins11120734.

Le Gall JR, Lemeshow S, Saulnier F. A new Simplified Acute Physiology Score (SAPS II) based on a European/North American multicenter study. JAMA. 1993;270:2957–63. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.270.24.2957.

Vincent JL, Moreno R, Takala J, Willatts S, De Mendonça A, Bruining H, et al. The SOFA (Sepsis-related Organ Failure Assessment) score to describe organ dysfunction/failure. Intensive Care Med. 1996;22:707–10. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF01709751.

Khwaja A. KDIGO clinical practice guidelines for acute kidney injury. Nephron Clin Pract. 2012;120:c179–84. https://doi.org/10.1159/000339789.

ARDS Definition Task Force, Ranieri VM, Rubenfeld GD, Thompson BT, Ferguson ND, Caldwell E, et al. Acute respiratory distress syndrome: the Berlin Definition. JAMA. 2012;307:2526–33. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2012.5669.

Singer M, Deutschman CS, Seymour CW, Shankar-Hari M, Annane D, Bauer M, et al. The third international consensus definitions for sepsis and septic shock (Sepsis-3). JAMA. 2016;315:801–10.

Kalil AC, Metersky ML, Klompas M, Muscedere J, Sweeney DA, Palmer LB, et al. Management of adults with hospital-acquired and ventilator-associated pneumonia: 2016 Clinical Practice Guidelines by the Infectious Diseases Society of America and the American Thoracic Society. Clin Infect Dis. 2016;63:e61-111. https://doi.org/10.1093/cid/ciw353.

De la Calle C, Morata L, Cobos-Trigueros N, Martinez JA, Cardozo C, Mensa J, et al. Staphylococcus aureus bacteremic pneumonia. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2016;35:497–502. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10096-015-2566-8.

Klindworth A, Pruesse E, Schweer T, Peplies J, Quast C, Horn M, et al. Evaluation of general 16S ribosomal RNA gene PCR primers for classical and next-generation sequencing-based diversity studies. Nucleic Acids Res. 2013;41:1–11. https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/gks808.

De Maio F, Posteraro B, Ponziani FR, Cattani P, Gasbarrini A, Sanguinetti M. Nasopharyngeal Microbiota Profiling of SARS-CoV-2 infected patients. Biol Proced. 2020;22:18. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12575-020-00131-7.

Bolyen E, Rideout JR, Dillon MR, Bokulich NA, Abnet CC, Al-Ghalith GA, et al. Reproducible, interactive, scalable and extensible microbiome data science using QIIME 2. Nat Biotechnol. 2019;37:852–7. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41587-019-0209-9.

Callahan B, McMurdie P, Rosen M, Han A, Johnson A, Holmes S. DADA2: High-resolution sample inference from Illumina amplicon data. Nat Methods. 2016;13:581–3. https://doi.org/10.1038/nmeth.3869.

Karstens L, Asquith M, Davin S, Fair D, Gregory WT, Wolfe AJ, et al. Controlling for contaminants in low-biomass 16S rRNA gene sequencing experiments. mSystems. 2019;4:e00290-19. https://doi.org/10.1128/mSystems.00290-19.

McMurdie PJ, Holmes S. phyloseq: an R package for reproducible interactive analysis and graphics of microbiome census data. PLoS ONE. 2013;8:e61217. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0061217.

Lozupone CA, Hamady M, Kelley ST, Knight R. Quantitative and qualitative β diversity measures lead to different insights into factors that structure microbial communities. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2007;73:1576–85. https://doi.org/10.1128/AEM.01996-06.

McMurdie PJ, Holmes S. Waste not, want not: why rarefying microbiome data is inadmissible. PLoS Comput Biol. 2014;10:e1003531. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pcbi.1003531.

Feng Y, Ling Y, Bai T, Xie Y, Huang J, Li J, et al. COVID-19 with different severities: a multicenter study of clinical features. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2020;201:1380–8. https://doi.org/10.1164/rccm.202002-0445OC.

Sepulveda J, Westblade LF, Whittier S, Satlin MJ, Greendyke WG, Aaron JG, et al. Bacteremia and blood culture utilization during COVID-19 surge in New York City. J Clin Microbiol. 2020;58:1–7. https://doi.org/10.1128/JCM.00875-20.

Calcagno A, Ghisetti V, Burdino E, Trunfio M, Allice T, Boglione L, et al. Co-infection with other respiratory pathogens in COVID-19 patients. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2021;27:297–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cmi.2020.08.012.

Garcia-Vidal C, Sanjuan G, Moreno-García E, Puerta-Alcalde P, Garcia-Pouton N, Chumbita M, et al. Incidence of co-infections and superinfections in hospitalized patients with COVID-19: a retrospective cohort study. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2021;27:83–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cmi.2020.07.041.

Cusumano JA, Dupper AC, Malik Y, Gavioli EM, Banga J, Berbel Caban A, et al. Staphylococcus aureus bacteremia in patients infected with COVID-19: a case series. Open Forum Infect Dis. 2020;7:ofaa518. https://doi.org/10.1093/ofid/ofaa518.

Giamarellos-Bourboulis EJ, Netea MG, Rovina N, Akinosoglou K, Antoniadou A, Antonakos N, et al. Complex immune dysregulation in COVID-19 patients with severe respiratory failure. Cell Host Microbe. 2020;27:992-1000.e3. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chom.2020.04.009.

Koulenti D, Tsigou E, Rello J. Nosocomial pneumonia in 27 ICUs in Europe: perspectives from the EU-VAP/CAP study. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2017;36:1999–2006. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10096-016-2703-z.

Giacobbe DR, Battaglini D, Ball L, Brunetti I, Bruzzone B, Codda G, et al. Bloodstream infections in critically ill patients with COVID-19. Eur J Clin Invest. 2020;50. https://doi.org/10.1111/eci.13319.

Goyal P, Choi JJ, Pinheiro LC, Schenck EJ, Chen R, Jabri A, et al. Clinical characteristics of covid-19 in New York City. N Engl J Med. 2020;382:2372–4. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMc2010419.

Buetti N, Ruckly S, de Montmollin E, Reignier J, Terzi N, Cohen Y, et al. COVID-19 increased the risk of ICU-acquired bloodstream infections: a case-cohort study from the multicentric OUTCOMEREA network. Intensive Care Med. 2021;47:180–7. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00134-021-06346-w.

Maes M, Higginson E, Pereira-Dias J, Curran MD, Parmar S, Khokhar F, et al. Ventilator-associated pneumonia in critically ill patients with COVID-19. Crit Care. 2021;25:25. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13054-021-03460-5.

Adeiza SS, Shuaibu AB, Shuaibu GM. Random effects meta-analysis of COVID-19/S. aureus partnership in co-infection. GMS Hyg Infect Control. 2020;15:Doc29. https://doi.org/10.3205/dgkh000364.

Woo S, Park S-Y, Kim Y, Jeon JP, Lee JJ, Hong JY. The dynamics of respiratory microbiota during mechanical ventilation in patients with pneumonia. J Clin Med. 2020;9:638. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm9030638.

Thibeault C, Suttorp N, Opitz B. The microbiota in pneumonia: from protection to predisposition. Sci Transl Med. 2021;13. https://doi.org/10.1126/scitranslmed.aba0501.

Rawson TM, Moore LSP, Zhu N, Ranganathan N, Skolimowska K, Gilchrist M, et al. Bacterial and fungal coinfection in individuals with coronavirus: a rapid review to support COVID-19 antimicrobial prescribing. Clin Infect Dis. 2020;71:2459–68. https://doi.org/10.1093/cid/ciaa530.

Roquilly A, Torres A, Villadangos JA, Netea MG, Dickson R, Becher B, et al. Pathophysiological role of respiratory dysbiosis in hospital-acquired pneumonia. Lancet Respir Med. 2019;7:710–20. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2213-2600(19)30140-7.

Gu S, Chen Y, Wu Z, Chen Y, Gao H, Lv L, et al. Alterations of the gut microbiota in patients with COVID-19 or H1N1 influenza. Clin Infect Dis. 2020. https://doi.org/10.1093/cid/ciaa709.

Su T-Y, Lee M-H, Huang C-T, Liu T-P, Lu J-J. The clinical impact of patients with bloodstream infection with different groups of Viridans group streptococci by using matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization-time of flight mass spectrometry (MALDI-TOF MS). Medicine. 2018;97:e13607. https://doi.org/10.1097/MD.0000000000013607.

Bos LDJ, Kalil AC. Changes in lung microbiome do not explain the development of ventilator-associated pneumonia. Intensive Care Med. 2019;45:1133–5. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00134-019-05691-1.

Souli M, Ruffin F, Choi S-H, Park LP, Gao S, Lent NC, et al. Changing characteristics of Staphylococcus aureus bacteremia: results from a 21-Year, prospective longitudinal study. Clin Infect Dis. 2019;69:1868–77. https://doi.org/10.1093/cid/ciz112.

Martin-Loeches I, J Schultz M, Vincent J-L, Alvarez-Lerma F, Bos LD, Solé-Violán J, et al. Increased incidence of co-infection in critically ill patients with influenza. Intensive Care Med. 2017;43:48–58. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00134-016-4578-y.

Rice TW, Rubinson L, Uyeki TM, Vaughn FL, John BB, Miller RR, et al. Critical illness from 2009 pandemic influenza A virus and bacterial coinfection in the United States. Crit Care Med. 2012;40:1487–98. https://doi.org/10.1097/CCM.0b013e3182416f23.

Acknowledgements

We are indebted to Valentina Di Gravio, research nurse at Fondazione Policlinico Universitario A. Gemelli IRCCS, for her help in patient selection and screening.

Funding

This work was supported by grants from the Italian Ministry for University and Scientific Research (GR-2018–12367375).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

GDP and FDM had full access to all the data in the study and take responsibility for the integrity and the accuracy of the data analysis. GDP, MA, FDM and BP conceived the study, and participated in its design and coordination and helped to draft the manuscript. FDM and GDP were in charge of the statistical analysis, participated in analysis and interpretation of data, helped to draft the manuscript, and critically revised the manuscript for important intellectual content. SC, GC, GDA, LM, GM, SLC, GB, EST, DLG, and RX collected the data for the study and participated in statistical analysis. GDP, FDM, GDA, MT, MS, BP and MA participated in the conception, design and development of the database, helped in analysis and interpretation of data, helped in drafting of the manuscript and critically revised the manuscript for important intellectual content. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The study was approved by the local ethics committees, (approval numbers: Comitato Etico UCSC reference number 23703/19). A written informed consent or proxy consent was obtained according to committee recommendations.

Consent for publication

Not applicable

Competing interest

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1. Figure S1:

e-diagram.

Additional file 2. eTable S1:

Characteristics of 48 study patients diagnosed with MRSA-VAP.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

De Pascale, G., De Maio, F., Carelli, S. et al. Staphylococcus aureus ventilator-associated pneumonia in patients with COVID-19: clinical features and potential inference with lung dysbiosis. Crit Care 25, 197 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13054-021-03623-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13054-021-03623-4