Abstract

Introduction

The aim of this study was to describe the clinical complications, treatment use, healthcare resource utilization (HCRU), and costs among patients with sickle cell disease (SCD) with recurrent vaso-occlusive crises (VOCs) in the US.

Methods

Merative MarketScan Databases were used to identify patients with SCD with recurrent VOCs from March 1, 2010, to March 1, 2019. Inclusion criteria were ≥ 1 inpatient or ≥ 2 outpatient claims for SCD and ≥ 2 VOCs per year in any 2 consecutive years after the first qualifying SCD diagnosis. Individuals without SCD in these databases were used as matched controls. Patients were followed for ≥ 12 months, from their second VOC in the 2nd year (index date) to the earliest of inpatient death, end of continuous enrollment in medical/pharmacy benefits, or March 1, 2020. Outcomes were assessed during follow-up.

Results

In total, 3420 patients with SCD with recurrent VOCs and 16,722 matched controls were identified. Patients with SCD with recurrent VOCs had a mean of 5.0 VOCs (standard deviation [SD] = 6.0), 2.7 inpatient admissions (SD 2.9), and 5.0 emergency department visits (SD 8.0) per patient per year during follow-up. Compared to matched controls, patients with SCD with recurrent VOCs incurred higher annual ($67,282 vs. $4134) and lifetime ($3.8 million vs. $229,000 over 50 years) healthcare costs.

Conclusion

Patients with SCD with recurrent VOCs experience substantial clinical and economic burden driven by inpatient costs and frequent VOCs. There is a major unmet need for treatments that alleviate or eliminate clinical complications, including VOCs, and reduce healthcare costs in this patient population.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Why carry out this study? |

Sickle cell disease (SCD) is a hereditary hemoglobinopathy associated with substantial clinical complications, including recurrent and painful vaso-occlusive crises (VOCs) as well as high healthcare resource utilization (HCRU) |

This real-world administrative claims-based analysis represents a novel and necessary assessment of clinical and economic outcomes in the vulnerable subset of patients with SCD with recurrent VOCs |

What was learned from this study? |

Patients with SCD with recurrent VOCs experienced a mean of 5.0 VOCs (standard deviation [SD] = 6.0), 2.7 inpatient admissions (SD 2.9), and 5.0 emergency department visits (SD 8.0) per patient per year |

Compared to matched controls, patients with SCD with recurrent VOCs had significantly higher annual ($67,282 vs. $4134) and lifetime ($3.8 million vs. $229,000 over 50 years) healthcare costs, highlighting the need for cost-effective therapies that reduce clinical complications in this patient population |

Introduction

Sickle cell disease (SCD) is a hereditary hemoglobinopathy impacting ~ 100,000 individuals in the US [1, 2]. SCD is caused by a point mutation in the gene that encodes β-globin (HBB) [3]. This mutation leads to the production of abnormal or sickled hemoglobin, which polymerizes in its deoxygenated form to promote a cycle of cellular adhesion, vaso-occlusion, endothelial dysfunction, and inflammation [4, 5]. As a result of vaso-occlusion, patients with SCD experience recurrent vaso-occlusive crises (VOCs) [5, 6], the hallmark clinical feature of SCD that contributes to the development of chronic pain, multi-organ failure, and early mortality [5,6,7]. Patients with SCD also experience other serious clinical complications, including anemia, avascular necrosis, retinopathy, infection, cardiopulmonary complications, frequent hospitalizations, and poor health-related quality of life [5, 6]. Most available treatment options reduce the severity of these clinical complications but do not eliminate them [5, 6]. Currently, the only curative option is allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation; however, given the stringent requirements for donors and recipients, only a small subset of patients are eligible to receive this treatment [5, 6].

In the US, 90% of adults with SCD report having ≥ 1 severe pain event in the past 12 months [8], and up to 67% have ≥ 3 VOCs per year [9]. VOCs are the most common cause of healthcare resource utilization (HCRU) among patients with SCD, contributing to 78% of their emergency department visits and 95% of their inpatient hospital admissions [10, 11]. Moreover, suboptimal management of VOCs during an initial hospitalization is associated with frequent readmission, often as early as 1 week post-discharge [11].

Previous studies have established that VOCs lead to substantial clinical and economic burden for patients with SCD. However, these studies have largely focused on the overall patient population with SCD [12, 13] or conducted secondary subgroup analyses on patients with specific numbers of VOCs [12, 14, 15]. As a result, data on the clinical complications, treatment use, HCRU, and costs are limited in patients with SCD with recurrent VOCs (defined as ≥ 2 VOCs per year for 2 consecutive years). Given that recurrent VOCs are associated with increased disease severity and premature mortality [16], there is a need to better understand how to optimize care for this more vulnerable subgroup of patients. Furthermore, previous studies have used a relatively narrow definition of “VOC,” which could have led to potential underestimation of costs in patients with SCD with recurrent VOCs. Use of a broader, composite definition of “VOC” (i.e., SCD with crisis, priapism, splenic sequestration, and acute chest syndrome) to identify and characterize patients with SCD has not been done before in administrative claims-based analyses and could enable a more comprehensive depiction of clinical and economic outcomes in this population. An unmet need to improve care for this subgroup of patients with recurrent VOCs remains. This retrospective real-world analysis aimed to address the limitations of the previous studies by identifying patients with SCD with recurrent VOCs and describing the economic and clinical burden associated with managing their recurrent VOCs in the US.

Methods

Study Design and Data Source

The Merative MarketScan Commercial, Medicare Supplemental, and Multi-State Medicaid Databases were used to identify patients with SCD with recurrent VOCs between March 1, 2010, and March 1, 2019. The full study period was from March 1, 2010, to March 1, 2020. During this time, inpatient medical, outpatient medical, and outpatient pharmacy data were available for ~ 89 million individuals and their dependents with commercial insurance coverage, ~ 4.6 million individuals with Medicare Supplemental coverage, and ~ 20 million individuals enrolled in Medicaid. Because these databases use only de-identified data, institutional review board approval was not required for this study.

Study Population

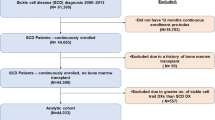

Patients of any age were eligible for inclusion if they either had ≥ 1 non-diagnostic inpatient claim or ≥ 2 non-diagnostic outpatient claims (service dates within 365 days of each other) with a diagnosis code for SCD between March 1, 2010, and March 1, 2019 (Fig. 1). Evidence of SCD with recurrent VOCs was based on the documentation of (1) SCD and (2) ≥ 2 VOCs per year in any 2 consecutive years after the date of the first qualifying diagnosis code for SCD. The index date was the date of the second VOC in the second of the 2 consecutive years. A VOC was defined as an inpatient or emergency department claim with a diagnosis code for acute chest syndrome, priapism, SCD with crisis, or splenic sequestration associated with SCD, and an accompanying Current Procedural Terminology (CPT) code for physician evaluation and management. VOCs were considered discrete events if they occurred ≥ 3 days apart from each other [12]. A minimum of 24 months of continuous enrollment before the index date and ≥ 12 months of continuous enrollment after and including the index date were required to be eligible for inclusion. Patients were excluded if they had ≥ 2 inpatient or outpatient claims with a diagnosis code for sickle cell trait or evidence of having received a hematopoietic stem cell transplant during the baseline or follow-up. All patients were followed for ≥ 12 months, beginning on the index date and ending on the earliest date of either inpatient death, end of continuous enrollment, or end of the study period (March 1, 2020).

Patient attrition. aClaims must have occurred within 365 days of each other. Only non-diagnostic claims were included; non-diagnostic claims are medical claims in which diagnosis codes reflect confirmed diagnoses rather than suspected diagnoses reported to justify diagnostic tests or procedures. bVOC claims were considered discrete events if they occurred ≥ 3 days apart from each other. BMT bone marrow transplant; HSCT hematopoietic stem cell transplant; SCD sickle cell disease; VOC vaso-occlusive crisis

To provide context around SCD-related healthcare costs, we matched each patient with SCD with recurrent VOCs to up to five individuals in the Merative MarketScan Databases without claims for SCD or other non-malignant blood disorders (e.g., anemia, β-thalassemia, etc.) on age, sex, geographic region, payer type, and amount of follow-up data. The index dates of controls in each database were randomly assigned based on the distribution of index dates of patients with SCD. Like patients with SCD, matched controls were required to have ≥ 24 months of continuous enrollment with medical and pharmacy benefits before the index date and ≥ 12 months of continuous enrollment with medical and pharmacy benefits after and including the index date to be eligible for inclusion.

Study Outcomes

Demographics, including age, sex, race, geographic region, and payer type, were assessed at the index date. Clinical (i.e., clinical complications and treatment use) and economic outcomes (i.e., HCRU and costs) were assessed during the variable-length follow-up.

Clinical complications were identified using non-diagnostic claims that contained diagnosis codes for complications of interest. Treatment use was determined by the presence of ≥ 1 medical or pharmacy claim for folic acid, hydroxyurea, iron chelation therapy (ICT), pain medications, and penicillin during the variable-length follow-up. The total number of claims for each treatment was also recorded. Only clinical complications and treatment use documented in > 10% of the overall cohort are reported here.

Annual HCRU included inpatient admissions, outpatient visits/encounters, and outpatient prescriptions. Outpatient visits/encounters included emergency department visits, physician office visits, laboratory encounters, and other service visits/encounters. Healthcare costs were based on paid amounts of adjudicated claims, including insurer and health plan payments as well as patient cost-sharing in the form of copayment, deductible, and coinsurance [17, 18].

Costs were reported per patient per year (PPPY) and adjusted for inflation to 2020 US medical prices using the Medical Care Component of the Consumer Price Index [19]. Lifetime healthcare costs were evaluated in pre-specified age categories (0–5 years, 6–10 years, 11–15 years, 16–20 years, 21–25 years, 26–30 years, 31–35 years, 36–40 years, 41–50 years, and ≥ 51 years) and through patients’ estimated life expectancies (LEs) as follows:

Lifetime healthcare costs were calculated with the assumption that a patient lived to 50 years of age and were not adjusted for expected mortality over time.

Statistical Analysis

Descriptive statistics were used to summarize the demographics of patients with SCD with recurrent VOCs as well as their clinical complications, treatment use, HCRU, and healthcare costs. Comparative analyses were also performed to evaluate differences in HCRU and costs between patients with SCD with recurrent VOCs and matched controls. T-tests were used to determine the statistical significance of differences for continuous variables, and chi-squared tests were used for categorical variables. A p value of < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Additional descriptive analyses were conducted in pre-specified patient subgroups based on age, payer type, and the mean number of VOCs they experienced per year in the variable-length follow-up. Clinical complications were summarized in patients who experienced < 2 or ≥ 2 VOCs per year during the variable-length follow-up and across three age cohorts (i.e., 0–11 years, 12–35 years, and ≥ 36 years). HCRU and costs were also summarized across more granular categories of VOC frequency (i.e., < 2, 2 to < 4, 4 to < 6, 6 to < 8, 8 to < 10, and ≥ 10 VOCs experienced per year during the variable-length follow-up) and across Medicaid and commercial payer types.

Results

Demographics and Payer Types

Overall, 3420 patients were identified as having SCD with recurrent VOCs and 16,722 individuals identified as matched controls (Fig. 1). Of the 3420 identified patients with SCD with recurrent VOCs, 2310 continued to experience ≥ 2 VOCs per year during the variable-length follow-up (i.e., after the index date). The mean age of the patients was 19.1 years (standard deviation [SD] = 12.8 years; range 2–67 years), approximately half were female (51.6%), and most were included in the Medicaid Database (80.0%). Both groups were balanced on matched characteristics after the matching criteria were applied (Table 1). The mean duration of follow-up for patients with SCD with recurrent VOCs was 4.2 years (SD 2.2 years).

Clinical Complications and Treatment Use

Overall, patients with SCD with recurrent VOCs had a mean of 5.0 VOCs PPPY (SD 6.0). Considered by payer type, patients in the Medicaid Database had a higher mean number of VOCs PPPY (5.3 [SD 6.2]) than patients in the Commercial Database (4.0 [SD 5.1]). The subgroup of patients who continued to experience ≥ 2 VOCs per year during the variable-length follow-up had a mean of 6.8 VOCs PPPY (SD 6.6). Clinical complications in patients with SCD with recurrent VOCs are described in Table 2. The prevalence of most complications was higher among older patients and those with higher numbers of VOCs during the variable-length follow-up (Supplementary Table 1).

Most patients with SCD with recurrent VOCs had ≥ 1 opioid claim (93.6%); the mean number of opioid claims PPPY was 9.7 (SD 12.9) (Table 3). A large proportion of patients had ≥ 1 hydroxyurea claim (68.0%) during the variable-length follow-up; the mean number of hydroxyurea claims PPPY was 2.6 (SD 3.2). The subgroup of patients who continued to experience ≥ 2 VOCs per year during the variable-length follow-up had a higher number of mean opioid claims PPPY (12.5 [SD 14.1]) than the overall cohort of patients with SCD with recurrent VOCs (Supplementary Table 2).

HCRU and Costs

Patients with SCD with recurrent VOCs had significantly higher HCRU than matched controls across all inpatient and outpatient HCRU variables assessed (Table 4). Compared to matched controls, patients with SCD with recurrent VOCs had a higher mean number of inpatient admissions PPPY (2.7 vs. 0.05; p < 0.0001) and emergency department visits PPPY (5.0 vs. 0.6; p < 0.0001) (Table 4). SCD with recurrent VOCs was also associated with higher total annual healthcare costs PPPY compared to matched controls ($67,282 vs. $4134; p < 0.0001); the overall cost differences between the two cohorts were primarily driven by inpatient costs (Fig. 2a). VOC-related costs PPPY comprised 71% of costs among patients with SCD with recurrent VOCs ($47,663 [SD $89,292]).

a Annual healthcare costs for all patients with SCD with recurrent VOCs, the subgroup of patients who continued to experience ≥ 2 VOCs per year during the variable-length follow-up, and matched controls, as well as b payer-specific annual healthcare costs for all patients with SCD with recurrent VOCs and the subgroup of patients who continued to experience ≥ 2 VOCs per year during the variable-length follow-up. aOutpatient visits/encounters included emergency department, physician office, laboratory, and other outpatient visits/encounters. PPPY per patient per year; SCD sickle cell disease; VOC vaso-occlusive crisis

Considered by payer type, patients with SCD with recurrent VOCs in the Medicaid Database had a higher mean number of emergency department visits PPPY than those in the Commercial Database (5.3 [SD 8.2] vs. 4.0 [SD 7.5]) and a higher mean number of outpatient prescriptions PPPY (36.9 [SD 29.3] vs. 27.7 [SD 22.6]) (Supplementary Table 3). In contrast, total annual healthcare costs were higher for patients covered by commercial insurance ($89,297) than for those covered by Medicaid ($61,655) (Fig. 2b).

The subgroup of patients who continued to experience ≥ 2 VOCs per year during the variable-length follow-up (n = 2310) had higher total annual healthcare costs than the overall group of patients with SCD with recurrent VOCs (N = 3420); the cost differences between the two groups persisted regardless of payer type (Fig. 2b). Mean annual VOC-related costs were also higher in this subgroup ($65,361 [SD $103,303]). Consistent with these findings, total annual healthcare costs in the overall cohort of patients with SCD with recurrent VOCs were higher in patients with higher numbers of VOCs. Patients with < 2 VOCs per year during the variable-length follow-up (n = 1110) had total annual healthcare costs of $25,138, and patients with ≥ 10 VOCs per year during the variable-length follow-up (n = 418) had total annual healthcare costs of $177,700 (Fig. 3).

Extrapolation of total annual healthcare cost data suggested that patients with SCD with recurrent VOCs would incur substantial healthcare costs over their lifetimes. By age 50, projected lifetime healthcare costs reached $3.8 million for all patients with SCD with recurrent VOCs and $4.6 million for the subgroup of patients who continued to experience ≥ 2 VOCs per year during the variable-length follow-up compared to $229,000 for matched controls (Fig. 4). Each additional year of life after age 50 added $102,262 to the total lifetime healthcare cost estimates for patients with SCD with recurrent VOCs, $129,340 for the subgroup of patients who continued to experience ≥ 2 VOCs per year during the variable-length follow-up, and $8253 for matched controls. Lifetime healthcare cost estimates continued to be highest among patients with ≥ 2 VOCs per year during the variable-length follow-up, regardless of payer type, and were also higher among patients covered by commercial insurance than among patients covered by Medicaid (Supplementary Fig. 1).

Lifetime healthcare costs for all patients with SCD with recurrent VOCsa, the subgroup of patients who continued to experience ≥ 2 VOCs per year during the variable-length follow-upb, and matched controlsc. aAnnual costs for patients with SCD with recurrent VOCs per age group were $24,697 (age 0–5 years [n = 503]), $33,499 (age 6–10 years [n = 473]), $54,715 (age 11–15 years [n = 504]), $81,875 (age 16–20 years [n = 657]), $95,082 (age 21–25 years [n = 436]), $83,612 (age 26–30 years [n = 247]), $98,964 (age 31–35 years [n = 208)], $82,573 (age 36–40 years [n = 143)], $105,580 (age 41–50 years [n = 152]), and $102,262 (age ≥ 51 years [n = 97]). bAnnual costs for patients in the ≥ 2 VOCs PPPY subgroup per age group were $34,191 (age 0–5 years [n = 234]), $48,581 (age 6–10 years [n = 252]), $68,295 (age 11–15 years [n = 341]), $99,588 (age 16 to 20 years [n = 506]), $104,578 (age 21 to 25 years [n = 367]), $101,813 (age 26–30 years [n = 194]), $121,490 (age 31–35 years [n = 152]), $98,856 (age 36–40 years [n = 102]), $135,580 (age 41–50 years [n = 103]), and $129,340 (age ≥ 51 years [n = 59]). cAnnual costs for matched controls per age group were $1423 (age 0–5 years [n = 2725]), $2334 (age 6–10 years [n = 2384]), $2947 (age 11–15 years [n = 2860]), $5517 (age 16–20 years [n = 2257]), $6040 (age 21–25 years [n = 2261]), $5523 [age 26–30 years [n = 1259]), $4351 (age 31–35 years [n = 1016]), $3984 (age 36–40 years [n = 405]), $7432 (age 41–50 years [n = 828]), and $8253 (age ≥ 51 years [n = 727]). K thousand; M million; SCD sickle cell disease; VOC vaso-occlusive crisis

Discussion

This study used administrative claims data to evaluate the real-world clinical complications, treatment patterns, HCRU, and costs associated with SCD with recurrent VOCs. During the variable-length follow-up, patients experienced substantial clinical complications and required frequent acute pain management. HCRU, annual healthcare costs, and lifetime healthcare costs were significantly higher for patients with SCD with recurrent VOCs than for matched controls. Total annual and projected lifetime healthcare costs were also higher in the subgroup of patients who continued to experience ≥ 2 VOCs per year during the variable-length follow-up. The differences in total annual healthcare costs between cohorts largely reflected the higher inpatient costs for patients with SCD with recurrent VOCs, most of which were attributable to VOC events, thus indicating that the number of VOCs substantially impacts healthcare costs for this patient population.

Among patients with SCD with recurrent VOCs, 26.5% had claims for chronic pain and 98.4% reported requiring medications to manage the pain and other outcomes associated with VOC events. These findings are consistent with the notion that VOCs are the defining clinical feature of SCD [5, 6] and the main cause of HCRU for patients with SCD [10, 11]. Opioids were the most prescribed pain medications, with the mean number of claims PPPY being greater for these medications than for any other pain medication evaluated. Although tailored opioid therapy can be used during acute events [20], hydroxyurea remains the recommended standard of care for managing pain that interferes with daily activities and quality of life in both pediatric and adult patients with SCD [20]. It is therefore notable that fewer patients had pharmacy claims for or documented use of hydroxyurea (2.6 claims PPPY [68.0%]) than they had for opioids (9.7 claims PPPY [93.6%]). Taken together, an unmet need for additional treatment options for preventing and managing acute and chronic pain in patients with SCD with recurrent VOCs remains; such treatment options could reduce the need for opioids in this population.

Total annual healthcare costs for patients with SCD with recurrent VOCs were > $67,000 PPPY. These costs were higher than those in matched controls and those in broader cohorts of patients with SCD, regardless of the number of VOCs [12, 14]. The finding of higher annual healthcare costs in patients with SCD with recurrent VOCs (i.e., ≥ 2 VOCs per year for 2 consecutive years) is broadly consistent with the findings of another published study involving patients who experienced ≥ 2 VOCs during a shorter 1-year follow-up period [14]. In both our study and the Shah et al. study, higher healthcare costs were predominantly driven by inpatient admissions [14]. Our study focused on patients with severe presentations of SCD, in line with the inclusion criteria of ongoing clinical trials in this therapy area [21], which likely explains the higher costs observed in patients with SCD with recurrent VOCs versus the broader cohorts of patients with SCD [12, 14]. Our study also uniquely utilized the MarketScan databases to include patients across all payer types, while the Shah et al. study utilized MarketScan databases to include only patients covered by commercial insurance as well as individual-level data files (i.e., the Research Identifiable File [RIF] and Medicaid Analytic eXtract [MAX]) for patients enrolled in Medicaid and/or Medicare [12, 14].

Total annual healthcare costs were also higher for patients covered by commercial insurance than for patients with SCD with recurrent VOCs covered by Medicaid, a finding that is consistent with the results of some [22] but not all previous studies of patients with SCD with recurrent VOCs within these payer groups [14, 23]. Other published studies have found similar costs between patients covered by Medicaid and commercial insurance [14] or an inverse relationship between commercial and Medicaid costs [23]. Differences in the findings between our study and the other studies referenced here may be driven by their use of a payment proxy, which imputed costs for Medicaid-covered patients with SCD with capitated plans [23] and could lead to higher Medicaid-related costs. Additional differences may also be driven by our focus on patients with recurrent VOCs (i.e., ≥ 2 VOCs per year for 2 consecutive years) as well as differences between studies in patient age and database use (i.e., MarketScan vs. RIF MAX) [14, 22]. Although total annual healthcare costs were higher for patients covered by commercial insurance in our analysis, patients covered by Medicaid had higher HCRU, which emphasizes the potential impact of different reimbursement rates across payer types on the healthcare costs of patients with SCD with recurrent VOCs; similar observations have been made in a prior study of patients with SCD [22]. Lower reimbursement rates for patients covered by Medicaid have been well documented for many diseases in the literature and likely drive the differences observed in annual and lifetime healthcare costs across payer types in patients with SCD with recurrent VOCs [24, 25].

Our study also confirms the notion of a strong, positive relationship between the number of VOCs and extent of HCRU in patients with ≥ 2 VOCs PPPY [12, 14, 15]. In our study, we found higher rates of inpatient admissions in the subgroup of patients who continued to experience ≥ 2 VOCs in the follow-up period, consistent with evidence that inpatient admissions increase with the number of VOCs [12, 14]. In our study, and others [12, 14], we combined VOC claims with service dates within < 3 days of each other as a single event to account for potential VOC events captured as claims on separate days, which limited the likelihood of overestimating the number of discrete VOC events. Although it is not possible to confirm that a patient meeting this definition had discrete VOCs, combining claims with service dates < 3 days apart is a common approach [12, 14] and increased the probability that each event represented a discrete VOC. Differences in the definitions of “VOC,” as well as inherent limitations of using administrative claims databases (e.g., misclassification bias, selection bias, etc.), can challenge comparisons across studies and impact study results. Furthermore, we used a broader definition of VOCs than that used in the Shah et al. [12] study, similar to that used in recent clinical trials [21], and captured claims for acute chest syndrome, priapism, SCD with crisis, or splenic sequestration associated with SCD. Our use of this broader definition of VOCs may have led to a higher number of VOCs being identified in this study. However, we also appreciate that the use of this composite definition is not common in clinical practice or administrative claims studies and therefore potentially reduces this study’s comparability to other published studies.

This study also found that patients covered by Medicaid had a higher number of VOCs and higher associated HCRU than patients covered by commercial insurance. Lack of access to adequate healthcare is a major challenge for patients with SCD, regardless of disease severity [26]. Increased reliance on emergency department care is common among patients with SCD, particularly due to a lack of physicians who specialize in the disease and during the transition from pediatric to adult care [26, 27]. Given that 90% of patients with SCD in the US are Black [26], structural and interpersonal racism also contributes to poor pain management and healthcare experiences [28] for this demographic. Proposed changes to the healthcare system to reduce the impact of racism on patients include developing formal, hospital-based systems to report racist behavior; using SCD-specific pain-management protocols; empowering patients to report concerns of racism; and developing partnerships with patients [28]. Ultimately, increasing access to quality healthcare for patients of all demographics is needed to minimize the clinical and economic burden of SCD, especially among Medicaid enrollees and other historically marginalized groups [26].

Several limitations in this study should be noted. First, it used administrative claims data collected for reimbursement purposes and is therefore subject to potential misclassification bias. Second, the sole reliance on direct costs in these analyses likely led to an underestimation of the economic burden of disease associated with SCD, given the significant indirect cost burden that has been reported in this population, such as negative effects on work productivity, non-work productivity, and daily activities [29, 30]. Inversely, the lifetime cost calculation used a simplifying assumption that patients with SCD will have severe disease from birth until death, which may have led to an overestimation of the actual lifetime costs in this patient population. However, our use of age-specific annual costs may have mitigated, to a degree, some of this limitation. Third, individuals who died, went on long-term disability, or did not meet eligibility criteria may have systematically different clinical outcomes than patients who met enrollment criteria. Fourth, this study did not account for any impact of recently approved therapies for SCD, such as L-glutamine, voxelotor, and crizanlizumab; therefore, pharmacy costs associated with experiencing recurrent VOCs may have been underestimated. Lastly, the results of this study may not be generalizable to patients without commercial insurance coverage, Medicare coverage, or Medicaid eligibility.

Conclusion

This study is the first to focus on clinical and economic outcomes in the subgroup of patients with SCD with recurrent VOCs, identified by having ≥ 2 VOCs per year for 2 consecutive years and using a broader composite definition for VOCs. These patients have substantial clinical complications, as well as significant HCRU and healthcare costs, largely driven by inpatient hospital admissions and the number of VOCs. Disease-modifying therapies that alleviate the clinical complications of SCD and eliminate recurrent VOCs, as well as increase access to care, are urgently needed to improve clinical and economic outcomes in this patient population.

Change history

11 September 2023

A Correction to this paper has been published: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12325-023-02629-4

References

Hassell KL. Population estimates of sickle cell disease in the US. Am J Prev Med. 2010;38:S512–21.

Hassell KL. Sickle cell disease: a continued call to action. Am J Prev Med. 2016;51:S1-2.

Finch JT, Perutz MF, Bertles JF, Dobler J. Structure of sickled erythrocytes and of sickle-cell hemoglobin fibers. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1973;70:718–22.

Sundd P, Gladwin MT, Novelli EM. Pathophysiology of sickle cell disease. Annu Rev Pathol. 2019;14:263–92.

Kato GJ, Piel FB, Reid CD, Gaston MH, Ohene-Frempong K, Krishnamurti L, et al. Sickle cell disease. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2018;4:18010.

Ware RE, de Montalembert M, Tshilolo L, Abboud MR. Sickle cell disease. Lancet. 2017;390:311–23.

Darbari DS, Sheehan VA, Ballas SK. The vaso-occlusive pain crisis in sickle cell disease: definition, pathophysiology, and management. Eur J Haematol. 2020;105:237–46.

Evensen CT, Treadwell MJ, Keller S, Levine R, Hassell KL, Werner EM, et al. Quality of care in sickle cell disease: cross-sectional study and development of a measure for adults reporting on ambulatory and emergency department care. Medicine (Baltimore). 2016;95: e4528.

Zaidi AU, Glaros AK, Lee S, Wang T, Bhojwani R, Morris E, et al. A systematic literature review of frequency of vaso-occlusive crises in sickle cell disease. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2021;16:460.

Yusuf HR, Atrash HK, Grosse SD, Parker CS, Grant AM. Emergency department visits made by patients with sickle cell disease: a descriptive study, 1999–2007. Am J Prev Med. 2010;38:S536–41.

Ballas SK, Lusardi M. Hospital readmission for adult acute sickle cell painful episodes: frequency, etiology, and prognostic significance. Am J Hematol. 2005;79:17–25.

Shah N, Bhor M, Xie L, Paulose J, Yuce H. Medical resource use and costs of treating sickle cell-related vaso-occlusive crisis episodes: a retrospective claims study. J Health Econ Outcomes Res. 2020;7:52–60.

Johnson KM, Jiao B, Ramsey SD, Bender MA, Devine B, Basu A. Lifetime medical costs attributable to sickle cell disease among nonelderly individuals with commercial insurance. Blood Adv. 2023;7:365–74.

Shah NR, Bhor M, Latremouille-Viau D, Kumar Sharma V, Puckrein GA, Gagnon-Sanschagrin P, et al. Vaso-occlusive crises and costs of sickle cell disease in patients with commercial, Medicaid, and Medicare insurance - the perspective of private and public payers. J Med Econ. 2020;23:1345–55.

Desai RJ, Mahesri M, Globe D, Mutebi A, Bohn R, Achebe M, et al. Clinical outcomes and healthcare utilization in patients with sickle cell disease: a nationwide cohort study of Medicaid beneficiaries. Ann Hematol. 2020;99:2497–505.

Darbari DS, Wang Z, Kwak M, Hildesheim M, Nichols J, Allen D, et al. Severe painful vaso-occlusive crises and mortality in a contemporary adult sickle cell anemia cohort. PLoS ONE. 2013;5(11): e79923.

Tan L, Reibman J, Ambrose C, Chung Y, Desai P, Llanos JP, et al. Clinical and economic burden of uncontrolled severe noneosinophilic asthma. Am J Manag Care. 2022;28:e212–20.

Zeiger R, Sullivan P, Chung Y, Kreindler JL, Zimmerman NM, Tkacz J. Systemic corticosteroid-related complications and costs in adults with persistent asthma. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2020;8:3455-65.e13.

Statistics USBoL. Measuring Price Change in the CPI: Medical care. Updated December 1, 2022. https://www.bls.gov/cpi/factsheets/medical-care.htm. Accessed 24 Jan 2023.

Brandow AM, Carroll CP, Creary S, Edwards-Elliott R, Glassberg J, Hurley RW, et al. American Society of Hematology 2020 guidelines for sickle cell disease: management of acute and chronic pain. Blood Adv. 2020;4:2656–701.

ClinicalTrials.gov. A Safety and Efficacy Study Evaluating CTX001 in Subjects With Severe Sickle Cell Disease. Updated December 6, 2022. https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT03745287. Accessed 24 Jan 2023.

Mvundura M, Amendah D, Kavanagh PL, Sprinz PG, Grosse SD. Health care utilization and expenditures for privately and publicly insured children with sickle cell disease in the United States. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2009;53:642–6.

Gallagher ME, Chawla A, Brady BL, Badawy SM. Heterogeneity of the long-term economic burden of severe sickle cell disease: a 5-year longitudinal analysis. J Med Econ. 2022;25:1140–8.

Millwee B, Quinn K, Goldfield N. Moving toward paying for outcomes in medicaid. J Ambul Care Manage. 2018;41:88–94.

Lopez E, Neuman T, Jacobson G, Levitt L. How much more than medicare do private insurers pay? A review of the literature. 2020. https://www.kff.org/medicare/issue-brief/how-much-more-than-medicare-do-private-insurers-pay-a-review-of-the-literature/. Accessed 15 Nov 2022.

Lee L, Smith-Whitley K, Banks S, Puckrein G. Reducing health care disparities in sickle cell disease: a review. Public Health Rep. 2019;134:599–607.

Hemker BG, Brousseau DC, Yan K, Hoffmann RG, Panepinto JA. When children with sickle-cell disease become adults: lack of outpatient care leads to increased use of the emergency department. Am J Hematol. 2011;86:863–5.

Powers-Hays A, McGann P. When actions speak louder than words—racism and sickle cell disease. N Engl J Med. 2020;383:1902–3.

Lubeck D, Agodoa I, Bhakta N, Danese M, Pappu K, Howard R, et al. Estimated life expectancy and income of patients with sickle cell disease compared with those without sickle cell disease. JAMA Netw Open. 2019;2: e1915374.

Holdford D, Vendetti N, Sop DM, Johnson S, Smith WR. Indirect economic burden of sickle cell disease. Value Health. 2021;24:1095–101.

Acknowledgements

Funding

The study and publication fees were supported by Vertex Pharmaceuticals Incorporated and CRISPR Therapeutics AG.

Medical Writing and Editorial Assistance

The authors thank Paula J. Smith of Merative for providing programming services and Ciara Silverman, PharmD, of Vertex Pharmaceuticals Incorporated for her support in drafting this manuscript and performing data analysis. Medical writing and editing support were provided by Brittany Y. Jarrett, PhD, Natalie Prior, PhD, Jenifer Li, MSc, and Nicholas Strange of Complete HealthVizion, IPG Health Medical Communications, Inc., Chicago, IL, USA, funded by Vertex Pharmaceuticals Incorporated.

Author Contributions

All authors met the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors (ICMJE) authorship criteria. Neither honoraria nor payments were made for authorship. Chuka Udeze, Kristin A. Evans, Yoojung Yang, Timothy Lillehaugen, Janna Manjelievskaia, and Biree Andemarium were responsible for the study conception and design. Kristin A. Evans, Timothy Lillehaugen, and Janna Manjelievskaia were responsible for data acquisition. All authors participated in data analysis or interpretation, drafted or critically revised the manuscript for intellectual content, gave final approval of the version to be published, and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Prior Presentation

Portions of these data were presented at the Academy of Managed Care Pharmacy (AMCP) Annual Meeting 2022, National Harbor, MD, USA, October 11–14, 2022; and Society for Medical Decision Making (SMDM) 2022, Seattle, WA, USA, October 23–26, 2022.

Disclosures

Chuka Udeze, Yoojung Yang, and Nanxin Li are employees of Vertex Pharmaceuticals Incorporated and may hold stock/stock options. Urvi Mujumdar is a former employee of Vertex Pharmaceuticals Incorporated and may hold stock/stock options. Kristin A. Evans and Timothy Lillehaugen are employees of Merative and may hold stock/stock options. Janna Manjelievskaia was an employee of Merative at the time of this analysis and is now employed by Veradigm. Biree Andemarium has received research funding from the American Society of Hematology, Connecticut Department of Public Health, Forma Therapeutics, Global Blood Therapeutics, Hemanext, HRSA, Imara, Novartis, and PCORI, and has served as an advisory board member or consultant for Agios, Aruvant, Bayer, bluebird bio, CRISPR Therapeutics AG, CVS/Accordant, Cyclerion, Emmaus, Forma Therapeutics, GBT, Genentech, Hemanext, Novartis, NovoNordisk, Roche, Sanofi, TerSera, Terumo, and Vertex Pharmaceuticals Incorporated.

Compliance with Ethics Guidelines

This study employed the Merative MarketScan Commercial, Medicare Supplemental, and Multi-State Medicaid Databases, which include only de-identified patient data; therefore, institutional review board approval was not required.

Data Availability

This study used data available from Merative. Restrictions apply to the availability of these data, which were used under a licensing agreement.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

The original online version of this article was revised due to correction in Fig 2 b.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Udeze, C., Evans, K.A., Yang, Y. et al. Economic and Clinical Burden of Managing Sickle Cell Disease with Recurrent Vaso-Occlusive Crises in the United States. Adv Ther 40, 3543–3558 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12325-023-02545-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12325-023-02545-7