Abstract

Introduction

Pain and frailty are prevalent conditions in the older population. Many chronic diseases are likely involved in their origin, and both have a negative impact on quality of life. However, few studies have analysed their association.

Methods

In light of this knowledge gap, 3577 acutely hospitalized patients 65 years or older enrolled in the REPOSI register, an Italian network of internal medicine and geriatric hospital wards, were assessed to calculate the frailty index (FI). The impact of pain and some of its characteristics on the degree of frailty was evaluated using an ordinal logistic regression model after adjusting for age and gender.

Results

The prevalence of pain was 24.7%, and among patients with pain, 42.9% was regarded as chronic pain. Chronic pain was associated with severe frailty (OR = 1.69, 95% CI 1.38–2.07). Somatic pain (OR = 1.59, 95% CI 1.23–2.07) and widespread pain (OR = 1.60, 95% CI 0.93–2.78) were associated with frailty. Osteoarthritis was the most common cause of chronic pain, diagnosed in 157 patients (33.5%). Polymyalgia, rheumatoid arthritis and other musculoskeletal diseases causing chronic pain were associated with a lower degree of frailty than osteoarthritis (OR = 0.49, 95%CI 0.28–0.85).

Conclusions

Chronic and somatic pain negatively affect the degree of frailty. The duration and type of pain, as well as the underlying diseases associated with chronic pain, should be evaluated to improve the hospital management of frail older people.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Why carry out this study? |

Frailty and pain are conditions in which prevalence increases with age. |

Many chronic diseases, especially those related to the musculoskeletal system and connective tissue, are involved in the origin of both frailty and pain. |

This paper investigates the relation between pain and frailty in hospitalized older patients. |

What was learned from the study? |

Chronic, widespread and somatic pain were negatively associated with frailty. |

The accurate assessment of pain and its therapeutic treatment should be evaluated to improve the management of frail hospitalized older people. |

Digital Features

This article is published with digital features to facilitate understanding of the article. To view digital features for this article go to https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.12982520.

Introduction

Age is frequently associated with pain and frailty. Chronic pain is clinically common, being present in about 66% of persons over the age of 65 years and mainly in women, who are affected three times as frequently as men [1,2,3]. Pain often presents as a recurrent symptom associated with acute and chronic inflammatory processes such as rheumatic and degenerative diseases. Among these, low back pain is the most common, affecting 33% of older people. Osteoarthritis involves major joints in about 12% of the world population, and rheumatoid arthritis is diagnosed in about 1–2% [4]. Pain is also a common symptom accompanying different chronic diseases such as cancer, diabetes, neurodegenerative diseases, and liver, renal and cardiovascular diseases, their common denominators being the presence of chronic pain and advanced age.

Chronic pain impairs quality of life and the ability to maintain an independent lifestyle, productivity and social relationships [5, 6]; thus older people often experience mood and anxiety disorders [7, 8]. Zis and collaborators showed that about 13% of older adults suffered from both major depression and chronic pain simultaneously, although this prevalence may vary in different populations, and the authors highlight how the two conditions might be risk factors for each other [9]. In turn, depression increases the perception of pain, thus triggering a vicious circle, suggesting a possible role of neuroinflammation as a common pathogenic factor for the development of both chronic pain and depression [9]. Apart from depression, many other causes and consequences of chronic pain share common mechanisms with the development of frailty [10].

Frailty is an age-related syndrome due to a multidimensional process leading to increased vulnerability, reduced ability to respond to stressors, adverse health outcomes and also death [12,13,14,15]. In older adults, persistent pain might lead to a loss of physiological reserves and impaired mobility, thus contributing to the likelihood of frailty [11]. There is still ongoing debate regarding the most suitable operational definition and assessment instruments for use in clinical practice to define frailty. The frailty phenotype described by Fried, which is based on five criteria related to compromised physical performance [12], and the frailty index (FI) based on age-related accumulation of deficits proposed by Rockwood and Mitnitski are the most common [16]. Regardless of the method, frailty and pre-frailty increase in prevalence with aging and are more frequent in women [12, 17]. These features have similarities with those of chronic pain, such that many causes and effects of pain are embedded in the definition of frailty. There are at the moment only a few studies that directly correlate pain with frailty [10, 18, 19], and they are confined to the primary care setting. With the hypothesis that early recognition and adequate management of pain might be of crucial importance in hospitalized older adults in order to prevent or slow frailty, the objective of this study was to evaluate whether there was an association between pain and frailty in a population of older patients acutely hospitalized in internal medicine and geriatric wards.

Methods

Data Collection

Data were obtained from REPOSI (REgistry POlitherapy SIMI), an ongoing collaboration between the Italian Society of Internal Medicine (SIMI), IRCCS Fondazione Ca’ Granda Ospedale Maggiore Policlinico and IRCCS “Mario Negri” Institute of Pharmacological Research involving a network of more than 100 internal medicine and geriatric hospital wards throughout Italy. The REPOSI register enrols patients ≥ 65 years old acutely admitted to the participating wards during four index weeks 3 months apart. Data were initially obtained every 2 years (in 2010, 2012 and 2014), and are now collected yearly, beginning in 2016. Greater detail is provided elsewhere [15, 20]. The minimum data set includes sociodemographic factors, laboratory parameters, performance in activities of daily living (ADL) according to the Barthel Index (BI) [21], cognitive skills via the Short Blessed Test (SBT) [22], patterns of co-morbidities and their severity according to the Cumulative Illness Rating Scale (CIRS) [23], and drugs prescribed on admission, during hospital stay and at discharge. The study was conducted according to Good Clinical Practice guidelines and the Declaration of Helsinki. The study was approved by the Ethical Committee of the IRCCS Ca’ Granda Maggiore Policlinico Hospital Foundation of Milan and by the ethics committees of the participating centres (Supplementary Material). All patients provided signed informed consent.

Pain and Frailty Assessment

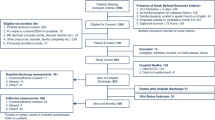

Patients enrolled from 2012 onward were eligible for the present analysis, because in previous REPOSI runs, no information on pain was collected. Patients with all the information available for the computation of the frailty index were assessable for the present analysis.

Frailty was measured according to the frailty index previously published within the framework of the REPOSI register [24], and based upon the procedure outlined by Searle [25]. The index includes 34 items related to nutrition using the body mass index (BMI), ability to perform activities of daily living (BI), cognition (SBT), mood (e.g. diagnosis of depression and anxiety), laboratory parameters (e.g. haemoglobin, platelets, white blood cells, creatinine clearance) and main chronic diseases reported in the CIRS (e.g. severity of hypertension, heart failure, ischaemic heart disease, stroke, diabetes, dyslipidaemias, thyroiditis, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease [COPD], kidney failure [CKD], upper and lower gastrointestinal diseases, liver disease, tumours, musculoskeletal diseases, Parkinson disease and psychiatric disorders). Patients were stratified into three groups according to their increasing degree of frailty: not frail (F0), moderately frail (F1) and severely frail (F2). The cut-off values were assessed according the 33th and 67th percentiles of the FI distribution.

Pain and some of its characteristics, including its temporal duration (acute or chronic), type (somatic, visceral, neuropathic), localizations (localized, widespread), causes and intensity (ranked from 0 to 10 according to the Numeric Rating Scale, NRS), were self-reported by patients and assessed at the moment of hospital admission.

Statistical Analysis

Data were summarized as frequencies (%), medians and interquartile ranges (IQR), or means and standard deviations (SD) as appropriate. A proportional odds ordinal logistic regression model (POM) was used to assess whether pain and its characteristics were associated with increasing severity of frailty. In the ordinal regression model, the response variable was the severity of frailty assessed by the three tiers of the FI introduced above, and all models were adjusted for sex and age.

In the ordinal regression model, the frequencies of each response category (e.g. F2), and of those above (F1/F2), were in turn considered and compared with the frequencies of those below (F1/F0 or F0), so that two separate comparisons were obtained. POM assumes that the effect of any covariate is the same across all comparisons, so that only one set of regression coefficients (and therefore only one odds ratio for each predictor) should be estimated. Accordingly, the regression model can be expressed as:

The POM assumption was checked by the score test and graphical methods. Results were expressed as odds ratio (OR) and 95% confidence interval (CI). The analysis was performed using SAS version 9.4 software (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA).

Results

Among 4827 patients enrolled in the REPOSI register since 2012, 3577 (74.1%) were assessable for the computation of the FI. The sample was well balanced for gender, with a mean age (SD) of 79.1 (7.6) years, and the FI distribution was positively skewed, with a mean of 0.27 and SD of 0.14. In particular, 1177 were not frail (F0), with a FI ≤ 0.19, 935 were moderately frail (F1), with a FI between 0.19 and 0.32, and 1169 were severely frail (F2), with FI > 0.32. Frailty increased with age, but with no significant difference between males and females after adjustment for age.

Table 1 shows the characteristics of 3577 patients according to the degree of frailty. Among patients, 884 (24.7%) suffered from pain, and in particular 379 (42.9%) had chronic pain. Somatic pain was the most common type of pain occurring in 400 patients (45.2%). Furthermore, 48 patients (5.5%) experienced widespread pain, and among the others, 195 patients (22.3%) suffered from pain involving two or more body sites, mainly the trunk and lower limbs.

Table 2 shows the results from the ordinal logistic regression model. In all the regression models, the chi-square score test failed to reject the null hypothesis of equal regression coefficients across response categories (p > 0.25); thus we may conclude that the proportional odds assumption holds. After adjusting for sex and age, there was an overall statistically significant association between pain and frailty (OR = 1.33, 95% CI 1.16–1.54). Specifically only patients suffering from chronic pain, but not those with acute pain, were more likely to be moderately to severely frail than those with no pain (OR = 1.69, 95% CI 1.38–2.07).

Somatic pain was associated with a higher degree of frailty than all other types of pain (OR = 1.60, 95% CI 1.22–2.07). Patients with widespread pain tended to be frailer than those suffering from localized pain (OR = 1.60, 95% CI 0.93–2.78), regardless of the number or specific sites involved. No relation was found between pain intensity and frailty, either in the overall population or in those with chronic pain.

Musculoskeletal conditions were the most common cause of persistent pain, particularly osteoarthritis, which accounted in our sample for almost one third of the cases, followed by rheumatoid arthritis and other rheumatic conditions (18.0%). Cancer was the other most frequent condition (Table 3). No relevant difference was found among the diseases leading to chronic pain (Table 4), but a lower degree of frailty was found in patients with pain caused by rheumatic conditions (OR = 0.49, 95%CI 0.28–0.85).

Discussion

This study investigated the association between pain and frailty along with its characteristics in a large sample of acutely hospitalized older patients. Despite the rather low prevalence of patients reporting pain, the results allow us to evaluate how pain and its characteristics are negatively associated with increasing frailty. Only a few studies have previously evaluated the relationship between pain and frailty [18, 19, 26, 27].

Pain and frailty present important differences. Pain, defined by the International Association for the Study of Pain (IASP) as “an unpleasant sensory and emotional experience associated with tissue damage, actual or potential”, is a subjective experience, generally considered a symptom of injury or disease. Frailty, on the other hand, is a biological condition derived from multiple clinical factors that indicate a more or less deficient condition of health. Our main finding was the association between chronic but not acute pain and a higher degree of frailty. The definition of chronic pain is still controversial. Typically, pain is considered chronic when it lasts or recurs over a period of more than 3–6 months [28, 29].

According to a more functional concept, chronic pain is triggered and maintained by biochemical and structural changes in the central nervous system, including glial activation and the onset of neuroinflammation, owing to an intense release of nociceptive stimuli over a long period of time [30, 31]. Notably, neuroinflammatory processes can be linked both to chronic pain and to depression, often present in these patients [9].

Persistent pain is typically the consequence of the presence of chronic diseases capable of generating persistent and intense stimuli. In our study, chronic pain was indeed associated with the type of underlying disease.

No significant differences in the frailty index were found between osteoarthritis, cancer and other less frequent diseases causing chronic pain. Exceptions were polymyalgia, rheumatoid arthritis and a few other musculoskeletal diseases, that presented with a lower risk of severe frailty than osteoarthritis (OR = 0.49). Furthermore, widespread rather than localized pain was associated with increasing frailty, and somatic rather than visceral and neuropathic pain was associated with a higher degree of frailty. On the other hand, the frailty index was not influenced by the intensity of pain, ranked as mild, moderate or severe [32, 33]. Surprised by this finding, we chose to evaluate pain intensity separately for chronic pain, but even this analysis failed to show a relationship with the frailty index. This apparent contradiction reinforces the view that the chronicity of pain rather than its severity is the main determinant of the degree of frailty.

With regard to pain generators, they were mainly related to chronic conditions strongly connected to chronic inflammatory processes, often widespread with multiple body localizations. Rheumatic diseases and cancer, the most frequent in our cases, are conditions associated with long-lasting and systemic inflammation. The high concentration of pro-inflammatory molecules bind to nociceptors and determine the sustained and continuous presence of painful stimuli, causing on the one hand a situation of permanent and widespread pain and, at the same time, the burden of progressing systemic disease.

In order to break this chain, one goal is to reduce the level of inflammation by means of preventive or therapeutic methods effective for both the cause (inflammation) and the effect (pain) [34].

Because both pain and frailty negatively affect quality of life in older people, better recognition of chronic pain and its management should become a target for intervention that may help to avoid the worsening of frailty in older hospitalized patients.

Limitations

This study on the relationship between pain and frailty was based upon data collected within the framework of a cross-sectional study. Even though the available data allow for an accurate assessment of the frailty index, data on pain and its characteristics are likely to be under-reported, with incomplete information, because its assessment may be hampered when communication problems exist, as is the case in patients with severe cognitive impairment or dementia. A more standardized and specifically-driven data collection method is therefore warranted, and only a prospective study would be able to provide further insights on the natural history of frailty and to assess the potential role of pain as a possible contributor to frailty. Furthermore, at variance with previous reports, we did not take into account physical frailty and characteristics such as weakness and exhaustion. Chronic conditions, such as musculoskeletal diseases and mood disorders, often leading to chronic pain, are also embedded in the definition of the frailty index itself, thus making it difficult to assess how they mediate and modulate the relationship between pain and frailty.

Conclusion

Chronic, diffuse and somatic pain associated with long-term chronic diseases is the expression of inflammatory processes, and reasonably affects at least in part the severity of frailty and quality of life in hospitalized older adults with multimorbidity. An accurate and more in-depth evaluation of pain and the recognition of its aetiology may help clinicians to manage these frail patients with effective results.

References

Molton IR, Terrill AL. Overview of persistent pain in older adults. Am Psychol. 2014;69(2):197–207. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0035794.

Corsi N, Roberto A, Cortesi L, et al. Prevalence, characteristics and treatment of chronic pain in elderly patients hospitalized in internal medicine wards. Eur J Intern Med. 2018;55:35–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejim.2018.05.031.

Latini R, De Marinis MG, Giordano F, et al. Epidemiology of chronic pain in the Latium Region, Italy: a cross-sectional study on the clinical characteristics of patients attending pain clinics. Pain Manag Nurs. 2019;20(4):373–81. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pmn.2019.01.005.

Neogi T, Zhang Y. Epidemiology of osteoarthritis. Rheum Dis Clin North Am. 2013;39:1–19. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rdc.2012.10.004.

Langley P, Müller-Schwefe G, Nicolaou A, Liedgens H, Pergolizzi J, Varrassi G. The societal impact of pain in the European Union: health-related quality of life and healthcare resource utilization. J Med Econ. 2010;13(3):571–81. https://doi.org/10.3111/13696998.2010.516709.

Gureje O, Von Korff M, Simon GE, et al. Persistent pain and well-being: a World Health Organization study in primary care. JAMA. 1998;280:147–51. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.280.2.147.

Evans DL, Charney DS, Lewis L, et al. Mood disorders in the medically ill: scientific review and recommendations. Biol Psychiatry. 2005;58:175–89. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biopsych.2005.05.001.

Currie SR, Wang J. Chronic back pain and major depression in the general Canadian population. Pain. 2004;107:64–3060. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pain.2003.09.015.

Zis P, Daskalaki A, Bountouni I, Sykioti P, Varrassi G, Paladini A. Depression and chronic pain in the elderly: links and management challenges. Clin Investig Aging. 2017;12:709–20. https://doi.org/10.2147/CIA.S113576.

Blyth FM, Rochat S, Cumming RG, et al. Pain, frailty and comorbidity on older men: the CHAMP study. Pain. 2008;140(1):224–30. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pain.2008.08.011.

Shega JW, Dale W, Andrew M, Paice J, Rockwood K, Weiner DK. Persistent pain and frailty: a case for homeostenosis. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2012;60(1):113–7. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1532-5415.2011.03769.x.

Fried LP, Tangen CM, Walston J, et al. Frailty in older adults: evidence for a phenotype. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2001;56:M146. https://doi.org/10.1093/gerona/56.3.m146.

Morley JE, Bcha MB, Vellas B, et al. Frailty consensus: a call to action. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2013;14(6):392–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jamda.2013.03.022.

Rockwood K, Song X, Macknight C, et al. A global clinical measure of fitness and frailty in elderly people. CMAJ. 2005;173:489–95. https://doi.org/10.1503/cmaj.050051.

Marcucci M, Franchi C, Nobili A, Mannucci PM, Ardoino I, REPOSI investigators. Defining aging phenotypes and related outcomes: clues to recognize frailty in hospitalized older patients. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2017;72(3):395–402. https://doi.org/10.1093/gerona/glw188.

Rockwood K, Mitnitski A. Frailty in relation to the accumulation of deficits. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2007;62:722–7. https://doi.org/10.1093/gerona/62.7.722.

Xue QL. The Frailty Syndrome: definition and natural history. Clin Geriatr Med. 2011;27(1):1–15. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cger.2010.08.009.

Coelho T, Paul C, Gobbens RJJ, Fernandes L. Multidimensional frailty and pain in community dwelling elderly. Pain Med. 2017;18:693–701. https://doi.org/10.1111/pme.12746.

Nakai Y, Makizako H, Kiyama R, et al. Association between chronic pain and physical frailty in community-dwelling older adults. J Environ Res Public Health. 2019;16(8):1330. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph16081330.

Franchi C, Mannucci PM, Nobili A, Ardoino I. Use and prescription appropriateness of drugs for peptic ulcer and gastrooesophageal reflux disease in hospitalized older people. Eur J Clin Pharma. 2020;76:459–65. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00228-019-02815-w.

Mahoney FI, Barthel DW. Functional evaluation: the Barthel index. Md State Med J. 1965;14:61–5.

Katzman R, Brown T, Fuld P, Peck A, Schechter R, Schimmel H. Validation of a short orientation-memory-concentration test of cognitive impairment. Am J Psychiatry. 1983;140:734–9. https://doi.org/10.1176/ajp.140.6.734.

Miller MD, Towers A. Manual of guidelines for scoring the cumulative illness rating scale for geriatrics (CIRS-G). Pittsburg: University of Pittsburgh; 1991.

Cesari M, Franchi C, Cortesi L, Nobili A, Ardoino I, Mannucci PM. Implementation of the Frailty Index in hospitalized older patients: results from the REPOSI register. Eur J Intern Med. 2018;56:11–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejim.2018.06.001.

Searle SD, Mitnitski A, Gahbauer EA, Gill TM, Rockwood K. A standard procedure for creating a frailty index. BMC Geriatr. 2008;8:24. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2318-8-24.

Saraiva MD, Suzuki GS, Lin SM, Ciampi de Andrade D, Jacob-Filho W, Suemoto CK. Persistent pain is a risk factor for frailty: a systematic review and meta-analysis from prospective longitudinal studies. Age Ageing. 2018;47:785–93. https://doi.org/10.1093/ageing/afy104.

Chiou J, Liu L, Lee W, et al. What factors mediate the inter-relationship between frailty and pain in cognitively and functionally sound older adults? A prospective longitudinal ageing cohort study in Taiwan. BMJ Open. 2018;8:e018716. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2017-018716.

Merskey H, Bogduk N. Classification of chronic pain. 2nd ed. Seattle: IASP Press; 1994.

Treede RD, Riefb W, Barke A, et al. A classification of chronic pain for ICD-11. Pain. 2015;156:1003–7. https://doi.org/10.1097/j.pain.0000000000000160.

Borsook D, Andrew M, Youssef AM, et al. When pain gets stuck: the evolution of pain chronification and treatment resistance. Pain. 2018;159:2421–36. https://doi.org/10.1097/j.pain.0000000000001401.

Fusco M, Skaper SD, Coaccioli S, Varrassi G, Paladini A. Degenerative joint diseases and neuroinflammation. Pain Pract. 2017;17(4):522–32. https://doi.org/10.1111/papr.12551.

Cleeland CS. Measurement of pain by subjective report. In: Chapman CR, Loeser JD, editors. Advances in pain research and therapy (vol 12): issues in pain measurement. New York: Raven Press; 1989. p. 391–403.

Rodríguez-Sánchez I, García-Esquinas E, Mesas AE, Martín-Moreno JM, Rodríguez-Mañas L, Rodríguez-Artalejo F. Frequency, intensity and localization of pain as risk factors for frailty in older adults. Age Ageing. 2019;48(1):74–80. https://doi.org/10.1093/ageing/afy163.

Tasneem S, Bin Liu B, Li B, Choudhary MI, Wang W. Molecular pharmacology of inflammation: medicinal plants as anti-inflammatory agents. Pharmacol Res. 2019;139:126–40. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.phrs.2018.11.001.

Acknowledgements

Funding

No funding or sponsorship was received for this study or publication of this article.

Authorship

All named authors meet the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors (ICMJE) criteria for authorship for this article, take responsibility for the integrity of the work as a whole, and have given their approval for this version to be published.

Authorship Contributions

I.A., C.F., A.N. and O.C. designed the study. I.A. performed statistical analysis. I.A., C.F. and O.C. interpreted the data and wrote the manuscript. All authors contributed to editing, reviewing, and approval of the manuscript.

List of Investigators

We acknowledge the clinicians who contributed to the REPOSI registry collection of data (Supplementary Appendix 1).

Steering Committee: Pier Mannuccio Mannucci (Chair) (Fondazione IRCCS Cà Granda Ospedale Maggiore Policlinico, Milano), Alessandro Nobili (co-chair) (Istituto di Ricerche Farmacologiche Mario Negri IRCCS, Milano), Antonello Pietrangelo (Presidente SIMI), Francesco Perticone (Direttore CRIS – SIMI), Giuseppe Licata (Socio d’onore SIMI), Francesco Violi (Policlinico Umberto I, Roma, Prima Clinica Medica), Gino Roberto Corazza, (Reparto 11, IRCCS Policlinico San Matteo di Pavia, Pavia, Clinica Medica I), Salvatore Corrao (ARNAS Civico, Di Cristina, Benfratelli, DiBiMIS, Università di Palermo, Palermo), Alessandra Marengoni (Spedali Civili di Brescia, Brescia), Francesco Salerno (IRCCS Policlinico San Donato Milanese, Milano), Matteo Cesari (UO Geriatria, Università degli Studi di Milano), Mauro Tettamanti, Luca Pasina, Carlotta Franchi (Istituto di Ricerche Farmacologiche Mario Negri IRCCS, Milano).

Clinical data monitoring and revision: Carlotta Franchi, Laura Cortesi, Mauro Tettamanti, Gabriella Miglio (Istituto di Ricerche Farmacologiche Mario Negri IRCCS, Milano).

Database Management and Statistics: Mauro Tettamanti, Laura Cortesi, Ilaria Ardoino, Alessio Novella (Istituto di Ricerche Farmacologiche Mario Negri IRCCS, Milano).

Investigators: Domenico Prisco, Elena Silvestri, Giacomo Emmi, Alessandra Bettiol, Irene Mattioli (Azienda Ospedaliero Universitaria Careggi Firenze, Medicina Interna Interdisciplinare); Gianni Biolo, Michela Zanetti, Giacomo Bartelloni (Azienda Sanitaria Universitaria Integrata di Trieste, Clinica Medica Generale e Terapia Medica); Massimo Vanoli, Giulia Grignani, Edoardo Alessandro Pulixi (Azienda Ospedaliera della Provincia di Lecco, Ospedale di Merate, Lecco, Medicina Interna); Graziana Lupattelli, Vanessa Bianconi, Riccardo Alcidi (Azienda Ospedaliera Santa Maria della Misericordia, Perugia, Medicina Interna); Domenico Girelli, Fabiana Busti, Giacomo Marchi (Azienda Ospedaliera Universitaria Integrata di Verona, Verona, Medicina Generale e Malattie Aterotrombotiche e Degenerative); Mario Barbagallo, Ligia Dominguez, Vincenza Beneduce, Federica Cacioppo (Azienda Ospedaliera Universitaria Policlinico Giaccone Policlinico di Palermo, Palermo, Unità Operativa di Geriatria e Lungodegenza); Salvatore Corrao, Giuseppe Natoli, Salvatore Mularo, Massimo Raspanti, (A.R.N.A.S. Civico, Di Cristina, Benfratelli, Palermo, UOC Medicina Interna ad Indirizzo Geriatrico-Riabilitativo); Marco Zoli, Maria Laura Matacena, Giuseppe Orio, Eleonora Magnolfi, Giovanni Serafini, Angelo Simili(Azienda Ospedaliera Universitaria Policlinico S. Orsola-Malpighi, Bologna, Unità Operativa di Medicina Interna); Giuseppe Palasciano, Maria Ester Modeo, Carla Di Gennaro (Azienda Ospedaliero-Universitaria Consorziale Policlinico di Bari, Bari, Medicina Interna Ospedaliera "L. D'Agostino", Medicina Interna Universitaria “A. Murri”); Maria Domenica Cappellini, Giovanna Fabio, Margherita Migone De Amicis, Giacomo De Luca, Natalia Scaramellini (Fondazione IRCCS Cà Granda Ospedale Maggiore Policlinico, Milano, Unità Operativa Medicina Interna IA); Matteo Cesari, Paolo Dionigi Rossi, Sarah Damanti, Marta Clerici, Simona Leoni, Alessandra Danuta Di Mauro (Fondazione IRCCS Cà Granda Ospedale Maggiore Policlinico, Milano, Geriatria); Antonio Di Sabatino, Emanuela Miceli, Marco Vincenzo Lenti, Martina Pisati, Costanza Caccia Dominioni (IRCCS Policlinico San Matteo di Pavia, Pavia, Clinica Medica I, Reparto 11); Roberto Pontremoli, Valentina Beccati, Giulia Nobili, Giovanna Leoncini (IRCCS Azienda Ospedaliera Universitaria San Martino-IST di Genova, Genova, Clinica di Medicina Interna 2); Luigi Anastasio, Maria Carbone (Ospedale Civile Jazzolino di Vibo Valentia, Vibo Valentia, Medicina interna); Francesco Cipollone, Maria Teresa Guagnano, Ilaria Rossi (Ospedale Clinicizzato SS. Annunziata, Chieti, Clinica Medica); Gerardo Mancuso, Daniela Calipari, Mosè Bartone (Ospedale Giovanni Paolo II Lamezia Terme, Catanzaro, Unità Operativa Complessa Medicina Interna); Giuseppe Delitala, Maria Berria, Alessandro Delitala (Azienda ospedaliera-universitaria di Sassari, Clinica Medica); Maurizio Muscaritoli, Alessio Molfino, Enrico Petrillo, Antonella Giorgi, Christian Gracin (Policlinico Umberto I, Sapienza Università di Roma, Medicina Interna e Nutrizione Clinica Policlinico Umberto I); Giuseppe Zuccalà, Gabriella D’Aurizio (Policlinico Universitario A. Gemelli, Roma, Roma, Unità Operativa Complessa Medicina d'Urgenza e Pronto Soccorso) Giuseppe Romanelli, Alessandra Marengoni, Andrea Volpini, Daniela Lucente (Unità Operativa Complessa di Medicina I a indirizzo geriatrico, Spedali Civili, Montichiari (Brescia) ); Antonio Picardi, Umberto Vespasiani Gentilucci, Paolo Gallo (Università Campus Bio-Medico, Roma, Medicina Clinica-Epatologia); Giuseppe Bellelli, Maurizio Corsi, Cesare Antonucci, Chiara Sidoli, Giulia Principato (Università degli studi di Milano-Bicocca Ospedale S. Gerardo, Monza, Unità Operativa di Geriatria); Franco Arturi, Elena Succurro, Bruno Tassone, Federica Giofrè (Università degli Studi Magna Grecia, Policlinico Mater Domini, Catanzaro, Unità Operativa Complessa di Medicina Interna); Maria Grazia Serra, Maria Antonietta Bleve (Azienda Ospedaliera "Cardinale Panico" Tricase, Lecce, Unità Operativa Complessa Medicina); Antonio Brucato, Teresa De Falco (ASST Fatebenefratelli - Sacco, Milano, Medicina Interna); Fabrizio Fabris, Irene Bertozzi, Giulia Bogoni, Maria Victoria Rabuini, Tancredi Prandini (Azienda Ospedaliera Università di Padova, Padova, Clinica Medica I); Roberto Manfredini, Fabio Fabbian, Benedetta Boari, Alfredo De Giorgi, Ruana Tiseo (Azienda Ospedaliera - Universitaria Sant'Anna, Ferrara, Unità Operativa Clinica Medica); Giuseppe Paolisso, Maria Rosaria Rizzo, Claudia Catalano (Azienda Ospedaliera Universitaria della Seconda Università degli Studi di Napoli, Napoli, VI Divisione di Medicina Interna e Malattie Nutrizionali dell'Invecchiamento); Claudio Borghi, Enrico Strocchi, Eugenia Ianniello, Mario Soldati, Silvia Schiavone, Alessio Bragagni (Azienda Ospedaliera Universitaria Policlinico S. Orsola-Malpighi, Bologna, Unità Operativa di Medicina Interna Borghi); Carlo Sabbà, Francesco Saverio Vella, Patrizia Suppressa, Giovanni Michele De Vincenzo, Alessio Comitangelo, Emanuele Amoruso, Carlo Custodero (Azienda Ospedaliero-Universitaria Consorziale Policlinico di Bari, Bari, Medicina Interna Universitaria C. Frugoni); Luigi Fenoglio, Andrea Falcetta (Azienda Sanitaria Ospedaliera Santa Croce e Carle di Cuneo, Cuneo, S. C. Medicina Interna); Anna L. Fracanzani, Silvia Tiraboschi, Annalisa Cespiati, Giovanna Oberti, Giordano Sigon (Fondazione IRCCS Cà Granda Ospedale Maggiore Policlinico, Milano, Medicina Interna 1B); Flora Peyvandi, Raffaella Rossio, Giulia Colombo, Pasquale Agosti (Fondazione IRCCS Cà Granda Ospedale Maggiore Policlinico, Milano, UOC Medicina generale – Emostasi e trombosi); Valter Monzani, Valeria Savojardo, Giuliana Ceriani (Fondazione IRCCS Cà Granda Ospedale Maggiore Policlinico, Milano, Medicina Interna Alta Intensità); Francesco Salerno, Giada Pallini (IRCCS Policlinico San Donato e Università di Milano, San Donato Milanese, Medicina Interna); Fabrizio Montecucco, Luciano Ottonello, Lara Caserza, Giulia Vischi (IRCCS Ospedale Policlinico San Martino e Università di Genova, Genova, Medicina Interna 1); Nicola Lucio Liberato, Tiziana Tognin (ASST di Pavia, UOSD Medicina Interna, Ospedale di Casorate Primo, Pavia); Francesco Purrello, Antonino Di Pino, Salvatore Piro (Ospedale Garibaldi Nesima, Catania, Unità Operativa Complessa di Medicina Interna); Renzo Rozzini, Lina Falanga, Maria Stella Pisciotta, Francesco Baffa Bellucci, Stefano Buffelli (Ospedale Poliambulanza, Brescia, Medicina Interna e Geriatria); Giuseppe Montrucchio, Paolo Peasso, Edoardo Favale, Cesare Poletto, Carl Margaria, Maura Sanino (Dipartimento di Scienze Mediche, Università di Torino, Città della Scienza e della Salute, Torino, Medicina Interna 2 U. Indirizzo d'Urgenza); Francesco Violi, Ludovica Perri (Policlinico Umberto I, Roma, Prima Clinica Medica); Luigina Guasti, Luana Castiglioni, Andrea Maresca, Alessandro Squizzato, Leonardo Campiotti, Alessandra Grossi, Roberto Davide Diprizio (Università degli Studi dell'Insubria, Ospedale di Circolo e Fondazione Macchi, Varese, Medicina Interna I); Marco Bertolotti, Chiara Mussi, Giulia Lancellotti, Maria Vittoria Libbra, Matteo Galassi, Yasmine Grassi, Alessio Greco (Università di Modena e Reggio Emilia, Azienda Ospedaliero-Universitaria di Modena; Ospedale Civile di Baggiovara, Unità Operativa di Geriatria); Angela Sciacqua, Maria Perticone, Rosa Battaglia, Raffaele Maio (Università Magna Grecia Policlinico Mater Domini, Catanzaro, Unità Operativa Malattie Cardiovascolari Geriatriche); Vincenzo Stanghellini, Eugenio Ruggeri, Sara del Vecchio (Dipartimento di Scienze Mediche e Chirurgiche, Unità Operativa di Medicina Interna, Università degli Studi di Bologna/Azienda Ospedaliero-Universitaria S.Orsola-Malpighi, Bologna); Andrea Salvi, Roberto Leonardi, Giampaolo Damiani (Spedali Civili di Brescia, U.O. 3a Medicina Generale); William Capeci, Massimo Mattioli, Giuseppe Pio Martino, Lorenzo Biondi, Pietro Pettinari (Clinica Medica, Azienda Ospedaliera Universitaria - Ospedali Riuniti di Ancona); Riccardo Ghio, Anna Dal Col (Azienda Ospedaliera Università San Martino, Genova, Medicina III); Salvatore Minisola, Luciano Colangelo, Mirella Cilli, Giancarlo Labbadia (Policlinico Umberto I, Roma, SMSC03 - Medicina Interna A e Malattie Metaboliche dell'osso); Antonella Afeltra, Benedetta Marigliano, Maria Elena Pipita (Policlinico Campus Biomedico Roma, Roma, Medicina Clinica); Pietro Castellino, Luca Zanoli, Alfio Gennaro, Agostino Gaudio (Azienda Ospedaliera Universitaria Policlinico – V. Emanuele, Catania, Dipartimento di Medicina); Valter Saracco, Marisa Fogliati, Carlo Bussolino (Ospedale Cardinal Massaia Asti, Medicina A); Francesca Mete, Miriam Gino (Ospedale degli Infermi di Rivoli, Torino, Medicina Interna); Carlo Vigorito, Antonio Cittadini, (Azienda Policlinico Universitario Federico II di Napoli, Napoli, Medicina Interna e Riabilitazione Cardiologica); Guido Moreo, Silvia Prolo, Gloria Pina (Clinica San Carlo Casa di Cura Polispecialistica, Paderno Dugnano, Milano, Unità Operativa di Medicina Interna); Alberto Ballestrero, Fabio Ferrando, Roberta Gonella, Domenico Cerminara (Clinica Di Medicina Interna ad Indirizzo Oncologico, Azienda Ospedaliera Università San Martino di Genova); Sergio Berra, Simonetta Dassi, Maria Cristina Nava (Medicina Interna, Azienda Ospedaliera Guido Salvini, Garnagnate, Milano); Bruno Graziella, Stefano Baldassarre, Salvatore Fragapani, Gabriella Gruden (Medicina Interna III, Ospedale S. Giovanni Battista Molinette, Torino); Giorgio Galanti, Gabriele Mascherini, Cristian Petri, Laura Stefani (Agenzia di Medicina dello Sport, AOUC Careggi, Firenze); Margherita Girino, Valeria Piccinelli (Medicina Interna, Ospedale S. Spirito Casale Monferrato, Alessandria); Francesco Nasso, Vincenza Gioffrè, Maria Pasquale (Struttura Operativa Complessa di Medicina Interna, Ospedale Santa Maria degli Ungheresi, Reggio Calabria); Leonardo Sechi, Cristiana Catena, Gianluca Colussi, Alessandro Cavarape, Andea Da Porto (Clinica Medica, Azienda Ospedaliera Universitaria, Udine). Nicola Passariello, Luca Rinaldi (Presidio Medico di Marcianise, Napoli, Medicina Interna); Franco Berti, Giuseppe Famularo, Patrizia Tarsitani (Azienda Ospedaliera San Camillo Forlanini, Roma, Medicina Interna II); Roberto Castello, Michela Pasino (Ospedale Civile Maggiore Borgo Trento, Verona, Medicina Generale e Sezione di Decisione Clinica); Gian Paolo Ceda, Marcello Giuseppe Maggio, Simonetta Morganti, Andrea Artoni, Margherita Grossi (Azienda Ospedaliero Universitaria di Parma, U.O.C Clinica Geriatrica); Stefano Del Giacco, Davide Firinu, Giulia Costanzo, Giacomo Argiolas (Policlinico Universitario Duilio Casula, Azienda Ospedaliero-Universitaria di Cagliari, Cagliari, Medicina Interna, Allergologia ed Immunologia Clinica); Giuseppe Montalto, Anna Licata, Filippo Alessandro Montalto (Azienda Ospedaliera Universitaria Policlinico Paolo Giaccone, Palermo, UOC di Medicina Interna); Francesco Corica, Giorgio Basile, Antonino Catalano, Federica Bellone, Concetto Principato (Azienda Ospedaliera Universitaria Policlinico G. Martino, Messina, Unità Operativa di Geriatria); Lorenzo Malatino, Benedetta Stancanelli, Valentina Terranova, Salvatore Di Marca, Rosario Di Quattro, Lara La Malfa, Rossella Caruso (Azienda Ospedaliera per l'Emergenza Cannizzaro, Catania, Clinica Medica Università di Catania); Patrizia Mecocci, Carmelinda Ruggiero, Virginia Boccardi (Università degli Studi di Perugia-Azienda Ospedaliera S.M. della Misericordia, Perugia, Struttura Complessa di Geriatria); Tiziana Meschi, Andrea Ticinesi, Antonio Nouvenne (Azienda Ospedaliera Universitaria di Parma, U.O Medicina Interna e Lungodegenza Critica); Pietro Minuz, Luigi Fondrieschi, Giandomenico Nigro Imperiale (Azienda Ospedaliera Universitaria Verona, Policlinico GB Rossi, Verona, Medicina Generale per lo Studio ed il Trattamento dell’Ipertensione Arteriosa); Mario Pirisi, Gian Paolo Fra, Daniele Sola, Mattia Bellan (Azienda Ospedaliera Universitaria Maggiore della Carità, Medicina Interna 1); Massimo Porta,Piero Riva (Azienda Ospedaliera Universitaria Città della Salute e della Scienza di Torino, Medicina Interna 1U); Roberto Quadri, Erica Larovere, Marco Novelli (Ospedale di Ciriè, ASL TO4, Torino, S.C. Medicina Interna); Giorgio Scanzi, Caterina Mengoli, Stella Provini, Laura Ricevuti (ASST Lodi, Presidio di Codogno, Milano, Medicina); Emilio Simeone, Rosa Scurti, Fabio Tolloso (Ospedale Spirito Santo di Pescara, Geriatria); Roberto Tarquini, Alice Valoriani, Silvia Dolenti, Giulia Vannini (Ospedale San Giuseppe, Empoli, USL Toscana Centro, Firenze, Medicina Interna I); Riccardo Volpi, Pietro Bocchi, Alessandro Vignali (Azienda Ospedaliera Universitaria di Parma, Clinica e Terapia Medica); Sergio Harari, Chiara Lonati, Federico Napoli, Italia Aiello (Ospedale San Giuseppe Multimedica Spa, U.O. Medicina Generale); Raffaele Landolfi, Massimo Montalto, Antonio Mirijello (Policlinico Universitario A. Gemelli- Roma, Clinica Medica); Francesco Purrello, Antonino Di Pino (Ospedale Garibaldi - Nesima – Catania, U.O.C Medicina Interna); Nome e Cognome del Primario, Silvia Ghidoni (Azienda Ospedaliera Papa Giovanni XXIII, Bergamo, Medicina I); Teresa Salvatore, Lucio Monaco, Carmen Ricozzi (Policlinico Università della Campania L. Vanvitelli, UOC Medicina Interna); Alberto Pilotto, Ilaria Indiano, Federica Gandolfo (Ente Ospedaliero Ospedali Galliera Genova, SC Geriatria Dipartimento Cure Geriatriche, Ortogeriatria e Riabilitazione).

Disclosures

Ilaria Ardoino, Carlotta Franchi, Alessandro Nobili, Pier Mannuccio Mannucci and Oscar Corli have nothing to disclose.

Compliance with Ethics Guidelines

The study was conducted according to Good Clinical Practice guidelines and the Declaration of Helsinki. The study was approved by the Ethical Committee of the IRCCS Ca’ Granda Maggiore Policlinico Hospital Foundation of Milan and by the ethics committees of the participating centres (Supplementary Material). All patients provided signed informed consent.

Data Availability

The data sets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Consortia

Corresponding author

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Ardoino, I., Franchi, C., Nobili, A. et al. Pain and Frailty in Hospitalized Older Adults. Pain Ther 9, 727–740 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40122-020-00202-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40122-020-00202-3