Abstract

The caprellid amphipod Caprella mutica is indigenous to coastal waters of north-east Asia and was first recorded in European waters in 1995. We now detected mass occurrences of > 3000 individuals per m2 in harbours of the two islands of Sylt and Helgoland in the German Bight, North Sea. Currently, Caprella mutica seems to be restricted to artificial hard substrata but we expect it to become a new species in natural hard bottom assemblages of that region as well.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The caprellid Caprella mutica originates from coastal waters of north-east Asia where it was first described by Schurin (1935) from Peter the Great Bay, Siberian coast of the Sea of Japan, and re-described by Arimoto (1976) and Platvoet et al. (1995; originally described as Caprella macho). Willis et al. (2004) gave a brief description of C. mutica recently found in Scotland.

In North European waters, C. mutica has been reported from the Netherlands (Platvoet et al. 1995), Norway (Wim Vader, pers. comm.), Ireland (Tierney et al. 2004) and from the Scottish west coast (Willis et al. 2004). In addition, there is anecdotal evidence about C. mutica occurring in Belgium. In the present paper we report on the occurrence of C. mutica in the south-eastern North Sea, and discuss briefly possible ways of introduction and the species habitat.

Methods

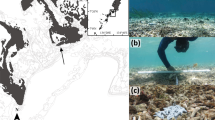

In 2004, first specimens of C. mutica were detected in the harbours of List/Sylt (55°01′N, 008° 26′E) and of the island of Helgoland (54°11′ N, 007°53′E). Careful inspection of material from previous years (fixed specimens and slides) confirmed the presence of C. mutica since 2000 or earlier. Following the first detection, densities of C. mutica were recorded in October 2004 by means of Scuba diving and by counting on pontoons that were just taken out of the water. Only specimens larger than 1 cm body length were counted. Individuals smaller than 1 cm body length were too thin and colourless for an appropriate in situ quantification. Body length of the largest individuals was measured from the basal part of antenna I to the posterior end of pereonite VII.

Results and discussion

The estimated abundances of C. mutica on harbour pontoons were > 3.000 individuals per m2 . Since only individuals larger than 1 cm body length were counted actual densities are probably much higher. In mid November, only specimens smaller than 1 cm body length were found, indicating that adult C. mutica die soon after their last brood in late fall. This kind of life history is common in amphipods of temperate regions (e.g. Bynum 1978).

Maximum body length of specimens found in the south-eastern North Sea was about 27 mm in males and 9 mm in females. This is slightly smaller than in Scottish specimens (up to 35.1 mm in males and 15.6 mm in females; Willis et al. 2004). The features of our individuals comply largely with the morphology of C. mutica. However, few characteristics remind of Caprella acanthogaster Mayer, another species indigenous to the Pacific Ocean (Krapp-Schickel, pers. comm.). The morphology and taxonomy of our specimens are currently investigated in detail.

Most likely, C. mutica reached European waters with shipments of Japanese oysters Crassostrea gigas (Thunberg) or in ballast water (Willis et al. 2004). It remains unclear how C. mutica reached the marinas of Sylt and Helgoland. Since C. mutica has no planktonic larval stage, it spends its entire life cycle attached to substrata. Thus, a direct transport is the most likely way of introduction to Sylt and Helgoland. Since both sites are regularly visited by small boats from many other marinas in the North Sea, C. mutica was possibly introduced while attached to boat hulls which are often covered with individuals (personal observation). Interestingly, the non-native Japanese brown seaweed Sargassum muticum (Yendo) Fensholt occurs abundantly along the North Sea coast including the islands of Helgoland and Sylt (Rueness 1989, Buschbaum 2005). Individuals of this seaweed disperse efficiently as floating thalli. It is known that caprellids attach to algae that may float for long distances (Thiel and Gutow 2005). C. mutica has been found attached to floating S. muticum in Japan (Sano et al. 2003) and “large caprellids” are commonly recorded on floating S. muticum near Helgoland (Saier, pers. comm.). Consequently, C. mutica may have reached the islands of Sylt and Helgoland via rafting.

C. mutica co-occurs with other introduced species such as the tunicate Styela clava Herdman and the Japanese oyster C. gigas on artificial hard substrata. By contrast, C. mutica has not yet been found in natural habitats. This is in accordance with findings of Willis et al. (2004) in Scottish waters where C. mutica was restricted to artificial structures such as mooring ropes, nets and boat hulls in marinas.

Since information on the ecology of C. mutica is scarce it is difficult to assess possible ecological effects on resident communities. The tunicate S. clava, too, was at first restricted to artificial hard substrata in harbours of the island of Sylt. But several years later it became a permanent member of epibenthic mussel beds (Mytilus edulis L.) (Buschbaum 2002). Possibly, the artificial hard substrata in the relatively sheltered harbour basins provide an intermediate habitat for new species where they may acclimatise for some years until spreading into natural habitats of the new location. Accordingly, C. mutica might spread on natural habitats, too. Future studies should address the population development and potential ecological impacts of this highly abundant newcomer.

References

Arimoto I (1976) Taxonomic studies of caprellids (Crustacea, Amphipoda, Caprellidae) found in the Japanese and adjacent waters. Spec Publs Seto Mar Biol Lab, Ser III

Buschbaum C (2002) Recruitment patterns and biotic interactions of barnacles (Cirripedia) on mussel beds (Mytilus edulis L.) in the Wadden Sea. Ber Polarforsch Meeresforsch 408

Buschbaum C (2005) Pest oder Bereicherung? Der eingeschleppte Japanische Beerentang Sargassum muticum an der deutschen Nordseeküste. Natur und Museum: in press

Bynum KH (1978) Reproductive biology of Caprella penantis Leach, 1814 (Amphipoda: Caprellidae) in North Carolina, U.S.A. Estuar Coast Mar Sci 7:473–485

Platvoet D, de Bruyne RH, Gmelig Meyling AW (1995) Description of a new Caprella-species from the Netherlands: Caprella macho nov. sp. (Crustacea, Amphipoda, Caprellidae). Bull Zool Mus Univ Amsterdam 15:1–4

Rueness J (1989) Sargassum muticum and other introduced Japanese Macroalgae: Biological Pollution of European coasts. Mar Poll Bull 20:173–176

Sano M, Omori M, Taniguchi K (2003) Predator-prey systems of drifting seaweed communities off the Tohoku coast, northern Japan, as determined by feeding habit analysis of phytal animals. Fish Sci 69:260–268

Schurin A (1935) Zur Fauna der Caprelliden der Bucht Peters des Grossen (Japanisches Meer). Zool Anz 122:198–203

Thiel M, Gutow L (2005) The ecology of rafting in the marine environment – II. The rafting organisms and community. Oceanogr Mar Biol 43 (in press)

Tierney TD, Kane F, Naughton O, Kennedy S, O‘Donohoe P, Copley L, Jackson D (2004) On the occurrence of the caprellid amphipod, Caprella mutica Schurin 1935, in Ireland. Ir Nat J 27:437–439

Willis KJ, Cook EJ, Lozano-Fernandez M, Takeuchi I (2004) First record of the alien caprellid amphipod, Caprella mutica, for the UK. J mar Biol Ass UK 84:1027–1028

Acknowledgements

Most of all we thank Traudl Krapp-Schickel for inspiring discussions on the taxonomy of C. mutica. We also thank Wim Vader and Kate Willis for help with species identification and are grateful to Bettina Saier and Werner Armonies for valuable comments on earlier drafts of this note. Yane Dreeskamp assisted in the field.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Communicated by H.-D. Franke

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Buschbaum, C., Gutow, L. Mass occurrence of an introduced crustacean (Caprella cf. mutica) in the south-eastern North Sea. Helgol Mar Res 59, 252–253 (2005). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10152-005-0225-7

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10152-005-0225-7